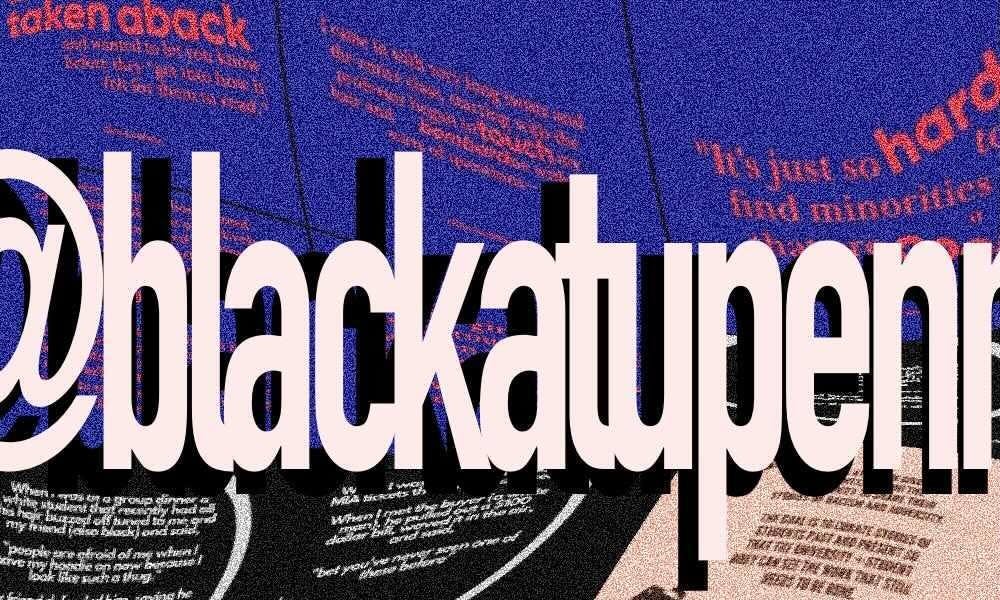

On June 18, 2020, the @BlackatUpenn Instagram account appeared. It came after a wave of private secondary schools and colleges created their own “Black at” pages for alumni and current students to anonymously express instances of anti–Blackness experienced at their predominantly–white educational institutions. The brief testimonies on Penn’s page showed evidence of classism, discrimination, and even fetishization of Black students on Penn’s campus. Though it amassed a large following in a brief time, the account made its ninth and final post just three weeks after its creation.

These stories, while often harrowing for many non–Black students to read, are by and large typical of predominantly–white universities. On an Ivy League campus such as Penn’s, where wealth and privilege are innate for many, experiences of subtle racism are strikingly commonplace for Black students.

The work of @BlackAtUpenn sought to bring light to the struggles of Penn's Black students and highlight shifts that still need to occur. Now, over a year has passed since the height of the Black Lives Matter movement. But what has really changed for Black students on Penn’s campus? Was the online activism of that summer, and the conversations sparked by @BlackatUPenn, indicative of tangible change?

Justin Arnold (C ‘22), co–chair of UMOJA, a coalition that aims to "unite students and student groups of the African Diaspora at the University of Pennsylvania," outlines what it was like to be a student at Penn during that summer’s racial unrest. “At Penn there’s so many different voices. There’s people who were posting Black squares thinking that’s some kind of form of activism, there’s people that were tweeting about it or making statements and trying to be supportive, but there are also people who don’t understand and want to be educated,” he explains. “I personally felt the burden to educate others. There was a burden of everything going on: the pandemic, the racial unrest, and being a student.”

In the wake of many high–profile police brutality cases in the summer of 2020, online and in–person activism reached unprecedentedly high levels. Companies and institutions alike released press statements recognizing the importance of anti–racism in the face of white supremacy. “Silence is violence,” activists and allies urged. And for a while, it seemed like those calls were being heard: People were speaking up, racist iconography was being removed, important discussions were being had around the globe. Penn's president, Amy Gutmann, released a statement reading “Today is not the first time—and it will not be the last time—that we speak up and stand up with our students, faculty, staff, alumni, and entire community of caring, loving, hurting human beings.”

Despite Gutmann’s pledge to speak up and stand up for Black students, Justin says, “There has been no change in how faculty are treating students, no change in how students are treating each other. I think some of the dialogue around racial justice has been disingenuous.”

Indeed, much of the activism that happened in 2020 was sharply criticized—the term “performative activism” became a staple of many conversations about Black Lives Matter. Activism trends, such as the posting of black squares on Blackout Tuesday, were widely criticized for being a display of solidarity to Black people that actually hid valuable information from BLM supporters online.

Other forms of online activism, like the Gen–Z–led slogan “Hello Kitty Says ACAB,” were lambasted as evidence that police brutality and institutional anti–Blackness were being commodified and even aestheticized by so–called "allies." Performative activism isn’t just online—the murder of Walter Wallace by Philadelphia police on October 26, 2020 reignited student’s concerns over Penn’s insincere handling of racial injustice. Former Street staffer Hannah Yusuf (C ‘21) criticized Penn’s response to the protests on and near Penn’s campus, stating that the University’s statement was a “slap in the face” to Black students.

Claire Kafeero (W ‘25), a member of Black Student League’s board, held a more optimistic view of Penn’s record on addressing white supremacy and institutional racism. Her high school was a predominantly–Black environment, so she explains that the racial unrest of that summer impacted what colleges she applied to and ultimately chose to attend. “I wanted to make sure that the school I was going to had some sense of a Black community, and that even if I did end up going to a predominantly–white space, that the administration would address these things. Penn has been vocal in letting people know that they support Black students.”

Nevertheless, Claire also acknowledges that Penn still has a long way to go towards being a truly racially equitable space. She feels that many non–Black students could better support their Black peers by simply being actively present. “When Black student organizations host events about microaggressions or other things, those events aren’t just for Black students. They’re for everyone. Seeing non–Black people in those spaces would be really powerful because it shows that they want to learn,” she says.

Both Justin and Claire argue that there’s a lot more for students and administrators to do to improve Penn for Black students. Anti–racist efforts are not the work of one summer; they are a constant learning process and an ongoing conversation. When administrators listen to the experiences of Black students and make policy decisions that aren’t just shallow statements of support, actual changes can happen over time.

Looking towards the future, Justin cites some of UMOJA’s main goals as getting a centralized space on campus for Black students to come together and receiving more access to funding and resources for Black organizations. Additionally, greater diversity among the Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) counselors and faculty as a whole are key ways that the University can offer greater support to Black students.

For Claire, microaggressions remain a crucial area of concern. Though many think of racism through "newsworthy" events, like police brutality and usage of racial slurs, Claire felt that the @BlackAtUpenn page essentially highlighted the role of microaggressions in the Black experience at Penn. As a first–year, Claire says “I’ve been in classrooms where I’ve shared an idea, and people will just completely go over what I say or it's not really respected.”

After the peak of the Black Lives Matter movement, it became clear to Black students that non–Black allies have the privilege of moving on. Meanwhile, Black students continue to face persistent issues of race that they encountered pre–summer 2020. They also bear the burden of continuously educating and re-educating their peers, over and over again. The stories outlined on the @BlackAtUpenn page are not relics of a time before Penn students enlightened themselves on racial injustice; they are likely testimonies of experiences that can, and do, still happen today.

The truth is that not much has changed for Black students since summer 2020, even if the amount of performative actions and statements have increased in quantity. Racism operates on the micro and macro level—even when it’s not in the news, Black students’ everyday Penn experiences are still shaped by it.

As we close out 2021 and move into 2022, it’s crucial for allies to remember that a lack of highly publicized protests doesn’t mean that it’s okay to see racial justice issues as confined to Penn’s past. Doing so only contributes to the legacy of Black students’ concerns being silenced or ignored. If @BlackAtUpenn taught us anything, it’s that looking at Penn from Black students’ perspectives paints a vastly different picture of the University—one that proves we must continue to reckon with the reality of racial injustice every day, instead of just when it’s convenient.