If you were to walk around Penn’s campus and ask any student about their high school resume, it’d probably be really lengthy and annoyingly impressive. Maybe they have hundreds of volunteer hours, won every debate tournament they went to, or excelled in academics while also playing a competitive sport.

We’d probably agree that they deserve their spot in school—we’d say they've earned it. But it would also serve as an indication of just how cutthroat and competitive the college admissions environment has become: presumably the reason why, in 2019, some of the wealthiest parents in the nation were indicted for buying their children’s way into prestigious universities.

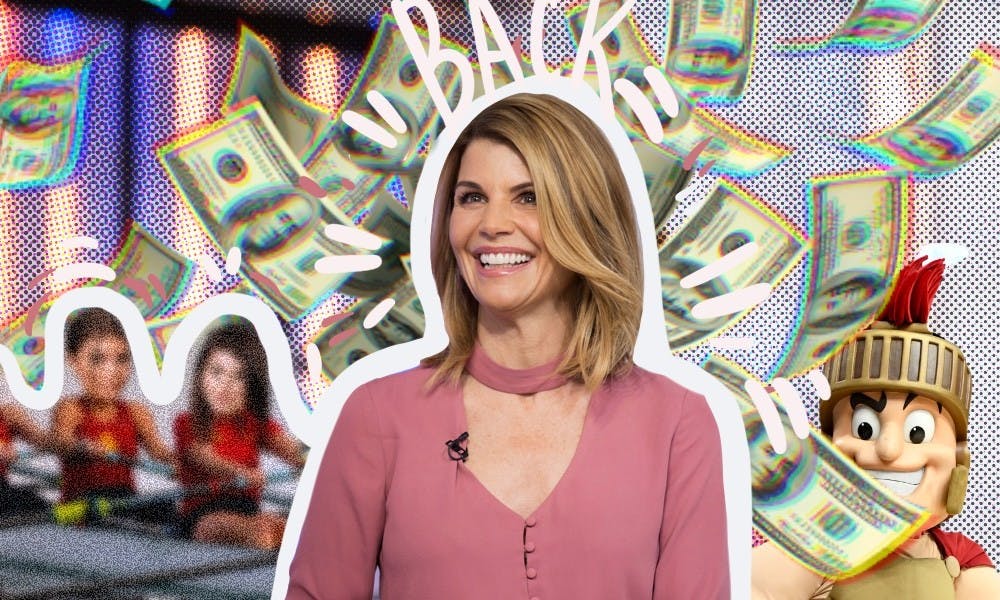

One of the most recognizable names involved in the scandal, Lori Loughlin, is best known for her endearing role as Aunt Becky in the classic sitcom, Full House. Her daughter, Olivia Jade Giannulli, also made a name for herself as a beauty guru and influencer with around two million YouTube subscribers before news of the admissions scandal broke.

Loughlin and her husband Mossimo Giannulli pled guilty to conspiracy to commit wire and mail fraud, and she served a two–month jail sentence for paying a $500,000 bribe to guarantee both of her daughters’ admission to the University of Southern California.

Now, Loughlin is returning to normalcy post–prison by reprising her role in the TV show When Hope Calls. Olivia Jade, after dropping out of college and taking a break from social media, is now back to her calling as an influencer—and she’s also a celebrity dancer on “Dancing with the Stars” this season. For the Loughlin–Giannulli family, things seem to be back to normal, despite some bumps in the road (lost Sephora sponsorships for Olivia Jade and prison time for her parents) along the way.

The college admissions scandal has mostly blown over now, despite the fact that charges were brought against 50 people and dominated the news cycles for a brief period of time. Still, the immense privilege of these wealthy, powerful families hasn’t changed at all—in fact, it almost seems like nothing really has changed.

Olivia Jade visited Jada Pinkett Smith’s Red Table Talks to break her silence about the college admissions scandal and says, “I’m not trying to victimize myself...I think a huge part of having privilege is not knowing you have privilege. And so, when it was happening, it didn’t feel wrong.” I would be inclined to agree with her on this point: many privileged people don’t understand their privilege because to them, it’s the norm—it’s expected.

Still, considering her family’s bribe in context of all of the other advantages she already has in the college admissions cycle exposes just how privileged they really are. And if that isn’t enough, the consequences, or lack thereof, should do the trick.

Researchers have found that SAT scores are correlated with income, and wealthy students receive significant advantages all throughout the college application process: access to tutors, college admissions advisors, and even resume ghostwriters. While many colleges are now test–optional, when considering the vast number of opportunities for academic support and achievement Olivia Jade and her sister Isabella had during their lives, it seems almost comical that Loughlin still paid half a million dollars to ensure their admission to a ‘good’ school.

While the steep price tag on the admissions scandal makes it seem like this crime might only apply to the egregiously wealthy, Kelley Williams–Bolar is an Ohio mom who was also convicted in 2011 for lying to help her kids attend better schools. Yet, there are some key differences between the two cases: instead of lying about her daughters’ athletic abilities and paying a hefty bribe, Williams–Bolar simply listed their father’s residency to send them to a better school in the neighboring school district.

Williams–Bolar said the Akron public schools her daughters could legally attend had “extensive water damage, mold, old and outdated textbooks, overworked teachers, [and] unruly classrooms.” Again, gaps in privilege within the education system are clear, especially when considering that children in school districts with the highest concentrations of poverty tend to score an average of more than four grade levels below children in the richest areas.

Both Williams–Bolar and the girls’ father were charged with felonies for falsification of records and theft of public education. The judge presiding over Williams–Bolar’s case ended up sentencing her to five years in prison, reduced to ten days in jail and 80 hours of community service. Around the same time, Tonya McDowell was convicted for enrolling her son in a different district’s elementary school. McDowell, a single mother experiencing homelessness, faced first–degree larceny and conspiracy to commit larceny charges—she ended up in jail, and her friend whose address she used for enrollment lost custody of her own children for a while and also wound up homeless.

A period of incarceration for Loughlin is not the same as a period of incarceration for Williams–Bolar and McDowell. And while their motivations were similar, to provide the best education possible for their children, Loughlin’s crime is steeped in privilege, one that helps her at every stage of her process through and out of the justice system.

Wealthier families have the option to donate large sums to universities. They’re likely to have the connections, resources, and experiences to understand how to propel their children to academic greatness, better jobs, and better outcomes. They can pull their kids out of public schools if they feel as though private schools can do a better job, send their children to tutors, or coach them through standardized tests that might move them from “honors” classes to “gifted” classes—the list goes on.

For many parents, like Williams–Bolar, McDowell, and countless others, there is no meaningful choice. How is it fair that they receive similar punishments to people like Loughlin, who have access to high–powered, expensive attorneys and can return to acting from a two–month stint in jail as if nothing happened?

After news of the “Varsity Blues” admission scandal broke, Loughlin pledged to pay $500,000 in tuition to help two unknown students through their four years at USC. It’s unknown where she found them, or what metrics she used to choose those two specific kids—we know nothing about them, and their anonymity is probably for the better. Loughlin’s act of goodwill is probably a major contribution to these students and their families, but hasn’t won over everyone still reeling from such an obvious show of privilege about the already–contentious topic of education’s relationship with income.

Penn didn’t emerge from the scandal unscathed either—former Penn coach Jerome Allen admitted to taking $300K in bribes in 2019, and an infamous DP opinion piece about the importance of legacy admissions sparked a heated conversation about privilege and awareness in the same year.

As we walk up the bridge on Locust, we pass over the names of dozens of families who have made huge contributions to Penn. We may even know some classmates with the same last names, with generations of alumni in their family or other powerful connections to Penn. The politics of college admissions is a confusing and unclear gray area, and there’s been a lot of debate about the ethics of what goes on in the black box of admissions. From the Asian discrimination lawsuit against Harvard to questions of fairness regarding legacy students, differing opinions about elite college admissions, privilege, and equity are not new—and they’re also present right here on our campus.