In the wake of 2020, many musicians felt compelled to comment on last year's mayhem through their art; Bo Burnham’s Inside dealt with personal complications from the pandemic, and Lil Baby’s Grammy–nominated single “The Bigger Picture” tackled police brutality and protests that occurred last summer. Similarly, Injury Reserve, also affected by personal loss, responded by largely reforming their sound. In 2021, they released one of the most disorienting albums that mainstream hip–hop has ever seen.

The group’s experimentation on By the Time I Get to Phoenix was inspired by a 2019 live performance they held behind an Italian restaurant in Stockholm, Germany. To complement the rough circumstances, the trio performed an improvisational set instead of songs from their self–titled debut album of that year. Afterwards, they decided to take their next project in a more experimental and loose direction, a choice only reinforced by the tumultuous first half of 2020. When the album was almost complete, rapper Jordan Groggs, also known as Stepa J. Groggs, wanted to name the album after “By the Time I Get to Phoenix,” a Glen Campbell song that was famously transformed into a progressive, 19–minute epic by Isaac Hayes in 1969.

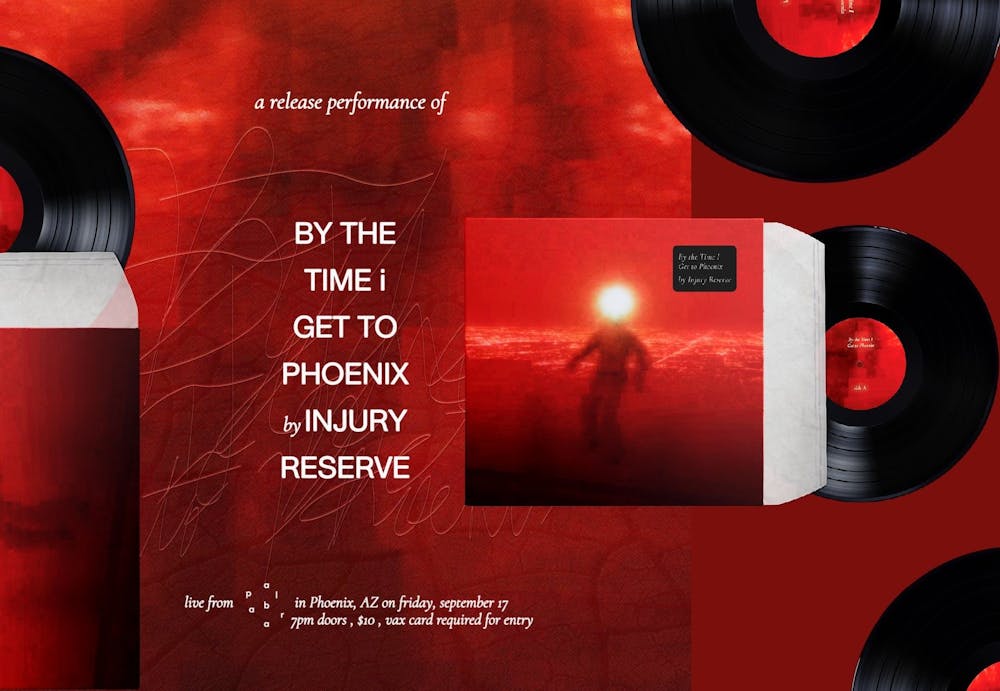

Unfortunately, tragedy struck when Groggs passed away in late June of 2020. After announcing his death on social media, the group fell silent for more than a year—only resurfacing later that summer to briefly promote Aminé’s album Limbo, on which they had featured. The remaining members, producer Parker Corey and rapper Nathaniel Ritchie, emerged on Aug. 10 this year with the announcement of an album and a new single, paying respects to Groggs with the album he had wanted. The emotional and unusually disorganized “Knees” came out that weekend.

When the overblown single “Superman That” quickly followed, it became clear that this album wouldn’t follow the formula of Injury Reserve’s previous record. Instead of lightly co–opting experimental hip–hop tropes into the more traditional forms of the genre, the group embraced past influences, such as glitch and trip–hop, and abandoned their pop–oriented structures. Across a scant 11 tracks and 41 minutes, the group views the world of 2020 through a lens of utter chaos—while championing resilience along the way.

The album’s opener, “Outside,” begins with a gloomy bass line paired with a dark rap battle excerpt before Ritchie launches into a deepened and hostile delivery. The tone is apocalyptic and frenzied as Ritchie slowly concludes his second verse: “There is no happy medium / That is nothing, that is nothing.” The drums return and coalesce with the synths to create a thrilling start to the album.

The bluesy “SS San Francisco” continues the heavy vocal processing into a chorus that includes a sample of post–punk band The Fall. Detroit rapper Zelooperz comes in as the only feature on the album, bringing a mostly abstract verse that ends with a tinge of antinatalism: “Scared to have some kids because the world be goin' through it.” It’s a fear that many others could have had during such a dark time, especially when dealing with a worsening climate, a worldwide pandemic, and political turmoil that had never been so vitriolic and intense.

“Footwork in a Forest Fire,” perhaps the most politically charged song on the album, offers another cacophonous soundscape while evoking police protests and the climate crisis in the lyrics. Groggs, in one of his only two verses on the entire record (the other being on “Knees”), sounds manic, offering lines like “If you don’t go, breath the air/ You might just stay alive,” and “I said, we down to riot / Sorry Mama, I try my best / To no longer be polite / They tryna take my life / And they take my rights.” The political imagery continues on “Ground Zero” as Ritchie quickly throws multiple references to the COVID–19 pandemic (masks, gloves, sanitizer, and goggles) over pounding percussion and shrill noise. Corey's production consistently matches the chaos that permeated those early months of 2020 and the issues that arose at that time.

Following these two tracks, “Smoke Don’t Clear” brings the most obvious IDM influence with its pulsing drum rhythm and Ritchie’s most guttural vocal inflections on the album. Loss takes center stage on the dystopian “Top Picks for You,” where Ritchie makes an interesting point about our technology as a discordant, buzzing synth grows louder: “Your patterns are still in place and your algorithm is still in action / Just workin' so you can just, jump right back in / But you ain’t jumpin' back.” This is a reference to how algorithms in social media and streaming services will keep recommending what they think you’ll like, even if you no longer exist. As a result, deceased people could always “jump right back in.”

The next track “Wild Wild West” is equal parts conspiracy parody and tribute to the Internet, which played a large influence in Injury Reserve’s trajectory. Afterwards, “Postpostpartum” contains perhaps the album’s most conventional instrumental as Ritchie comments on the steps that the group took to mature during the time of production.

“Knees,” the lead single, immediately strikes with sudden bursts of warm guitar leads with skipping drums underneath, with Ritchie reflecting on his past troubles with a soft and pained chorus: “Knees hurt me when I grow / And that’s a tough pill to swallow / Because I’m not gettin' taller.” His performance melts into Corey's hypnotic production until Groggs suddenly appears. “I can’t even grow no more,” his verse begins. He delves into his struggles with alcoholism, even recalling an aunt playfully mentioning his face being swollen as a side effect. Despite the dreary subject matter, the song reads like catharsis after the insane lows of the earlier tracks. At this point, the group processes their grief and attempts to move forward.

A sizable Brian Eno sample parades around the final track, “Bye Storm.” Compared to the rest of the album, the song is an optimistic conclusion; the production is hopeful, and Ritchie uses the storm analogy to talk about his fight against personal and universal turmoil: “It rains, it pours / But damn, man, it’s really pourin'.”

In an interview with Huck, Ritchie tries to sidestep the notion that Phoenix was an album produced in a vacuum of tragedy and grief. “I want people to know this isn’t a eulogy. We were ... having so much fun in these sessions,” he said. While the album’s sounds and themes are dreary, claustrophobic, and even terrifying at times, Injury Reserve wants their statement to not be one of hopelessness, but of strength in the face of such tumultuous and profound circumstances.