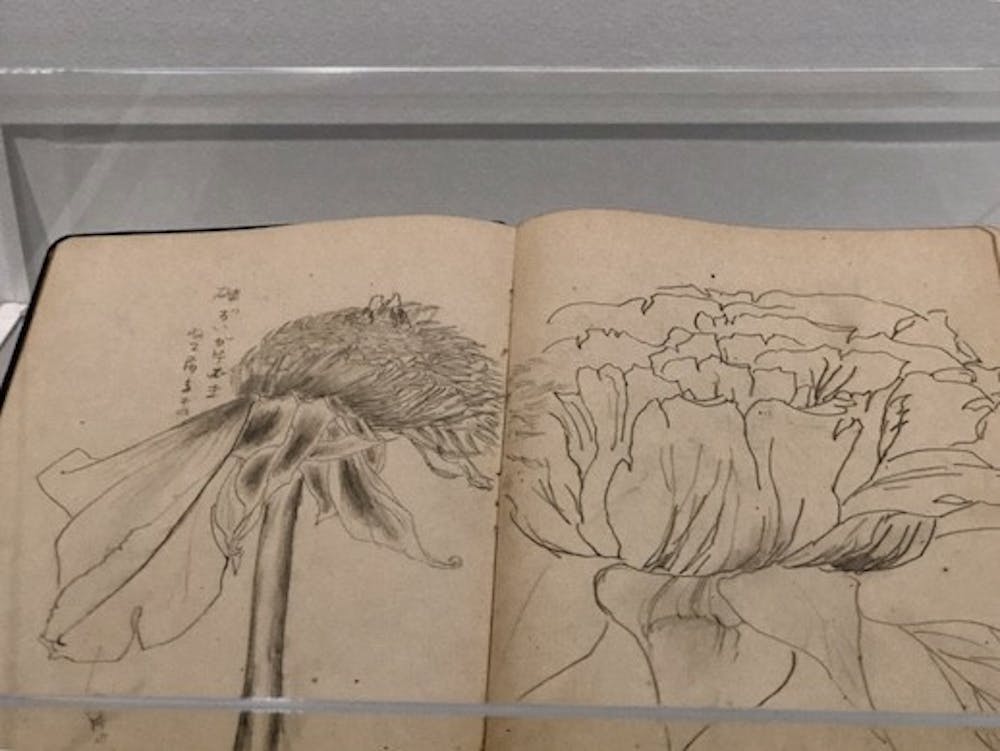

Yayoi Kusama was born among flowers. Her family owned and operated a plant nursery in Matsumoto, Japan that supplied the Nagano Prefecture with plants and seeds. This can be read from a placard in one of the galleries of Kusama’s new part–retrospective, part–exhibition, Cosmic Nature, at the Bronx Botanical Gardens. This particular viewing room was dedicated to Kusama’s early drawings: precise, diagrammatic sketches of tree peonies (Paeonia suffruticosa). Her dedication to realism and attention to detail at the precocious age of 16 recalls Picasso’s adage to “learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.”

The focal centerpieces of Cosmic Nature are far more abstract representations, but, in a way, are truer to life. According to the exhibition summary, “her lifelong project is one of awareness and attunement to the mysteries of the natural world.” Kusama’s early sketches look exactly like the objects of their depiction, but her sculptural work distills the attributes of the natural world that often go overlooked or unobserved. In fact, her depictions of plants, both familiar and unrecognizable, render their surroundings muted and two–dimensional by comparison.

Perhaps that can be attributed to my visit to the Botanical Gardens on a cloudy day in late July, when the polychromatic bloom of spring yielded to wilted flowers and acres of green grass. Whether intentionally or otherwise, Kusama had chosen a venue that stood in stark contrast to the art on display. The gardens were manicured and peaceful—nature rendered in still life. Meanwhile, “Dancing Pumpkin” is an immense riot of color and movement. More octopus than gourd, the sculpture’s palpable jubilation can’t help but bring a smile to your face.

In accord with Kusama’s goal to “call attention to the ... cycles of living things that are not always visible,” many of the pieces in Cosmic Nature capture the movement of plants which occurs too gradually to be detected by the human eye. Such moments of transition are depicted through iteration. The approach is best exemplified by the soft sculptures "Flower E," "Flower F," and "Flower Bud Opening to the Heavens." These oversized rambutan–esque growths in Kusama’s signature polka dots bloom into—or perhaps are overtaken by—tendrils that extend skywards. “Flower Obsession” is an interactive space wherein visitors plaster a greenhouse in floral stickers, in a clever inversion of plants growing unobserved. Relatedly, this installation’s floral network expands with every viewing.

The theme of growth reaches its apex of excess in the displays that border on lovecraftian horror, which is apropos, given that the subgenre also known as “cosmic horror” emphasizes the horror of the unknowable. In the atrium of the Mertz Library Building Gallery there’s an untitled cluster of tentacles, another Kusama trademark. The way they appear to burst out of the earth calls to mind a cthulhu deity, as much as it recalls weeds sprouting from the cracks in a city sidewalk. Housed in the Haupt Conservatory Galleries, “My Soul Blooms Forever” and “Hymn of Life–Tulips” both feature oversized steel flowers in bright colors. However, while the former’s blooms have an unimposing, inquisitive regard, the latter finds the same tulips twisted into ferocious shapes that resemble Gerald Anthony Scarfe’s animation for Pink Floyd’s The Wall.

Cosmic Nature isn’t just a journey through the life cycles of plants—their growth, reproduction, and decay—it’s also time travel through Kusama’s storied career as an artist. The indoor galleries at the Botanical Gardens feature tributes to her “Walking Piece” and her Infinity Nets series. “Narcissus Garden” is likewise an homage to an earlier piece, which Kusama originated in 1966. That first installation featured 1,500 steel spheres sold to passers–by as a representation of their own narcissism. The new incarnation of “Narcissus Garden” is a tranquil and meditative experience, watching the reflective globes mingle with the ducks and reeds of an artificial wetland. But the questions this new iteration provokes are unsettling; namely, what is the impact of human narcissism on the natural world?

At first glance, Yayoi Kusama’s art seems like perfect Instagram fodder. Without the benefit of getting up close and personal with these sculptures and installations, it would be easy to write off her exhibit as a slideshow of pop art pumpkins. But the scale of these pieces and the way they’re in dialogue with their surroundings cannot be captured secondhand. The best experiences in Cosmic Nature are the most immersive, like “Pumpkins Screaming About Love Beyond Infinity,” which immerses the viewer in an infinite array of glowing fruit. In these moments, Kusama’s presence is palpable. This is deliberate showmanship, but that doesn’t make it any less effective in capturing the first spark of a child’s imagination. Amidst the uncountable vegetation of the Botanical Gardens, Kusama succeeds, if momentarily, at transporting viewers back to her own childhood.

Yayoi Kusama's exhibition is a memorable collection that articulates the stillness and the motion of life which we take for granted, and she shows us through her own memories how to change that.