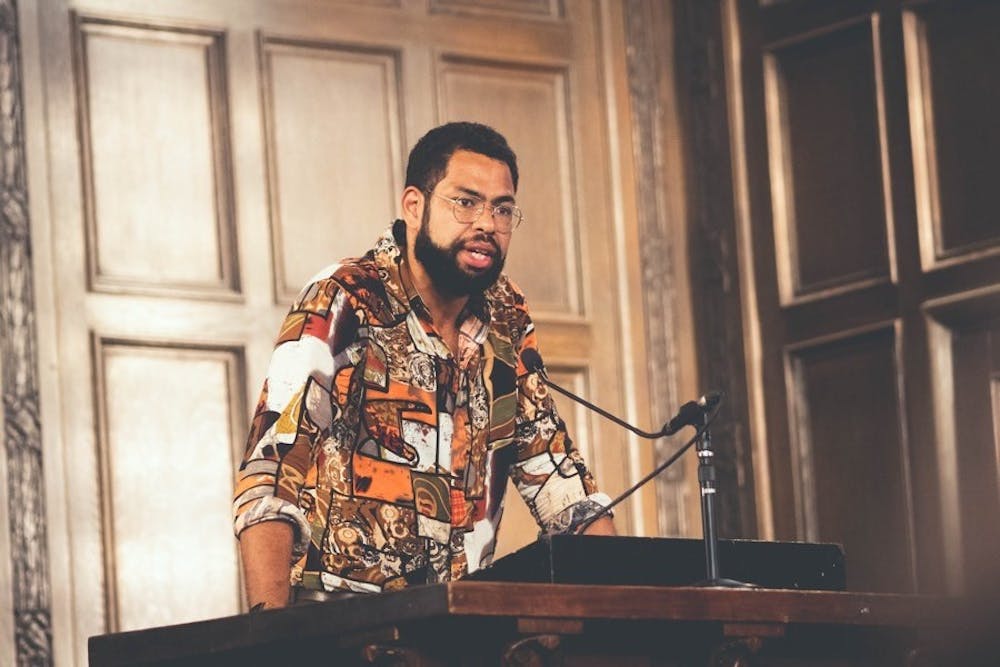

Rick Krajewski (E ’13) isn’t your typical politician, but perhaps that’s the point. The software–developer–turned–Reclaim–Philly–organizer went grassroots after a STEM curriculum he developed at a West Philly public school was shelved when the school morphed into privately run charter academy. Since then, he's helped elect District Attorney Larry Krasner, convinced thousands of Philadelphians to pay attention to judicial elections, and ousted a 35–year establishment incumbent to become West Philly’s state representative.

The magic of Krajewski is that he doesn’t feel like a political operative, his everyman energy genuine as curse words slip out mid–monologue. Krajewski admits what he doesn’t know and when he’s tired. He still considers himself a neighbor, even if his time is split between Baltimore Avenue and the quiet stress of Harrisburg. But mostly, Krajewski is worried about how an agenda steeped in restorative justice, education reform, and workers’ rights can gain traction without sacrificing the heart of socialism: radical and ever upward change.

As hoards of first years step onto a campus that often encompasses the battle between incrementalism and getting shit done, Street sat down with Krajewski to chat about what long–haul progressivism actually looks like, and, more importantly, how to settle into your new neighborhood.

34th Street Magazine: Thinking back to when you announced you were running for state rep., how has your motivation to serve West Philly evolved over the past 7 months?

I've lived in West and Southwest Philly my whole adult life. I want to start a family here. I want to have children here. I want to send them to a local school. I faced questions like, "Can I afford housing here?" "Can I feel confident in sending my child to a school that will be well funded and well supported?" "Will we have an environment that actually protects the health of my children, and the health of my neighbors and their children?" Those answers were not clear to me. So it was also obvious that to fight for those things, we need to understand the legislature more. Now, my motivations for being in the legislature and being a rep. have matured. Transforming our legislature is going to be a long–term project. It will require not just me being in office, but also having other champions in office that fight for progressive issues, and flipping control of the legislation to be democratically controlled. I both feel an intense urgency, but I also understand that it will be a long, long process.

Our district is one of the most interesting to represent because it’s so economically and ethnically diverse. How do you take into account the different, and potentially conflicting, needs of your constituents while drafting and voting on legislation?

As a rep., you have a few different considerations. There's your personal values and ideology, and then there are values of your district and the values of your party. One of the things that's tricky about being a rep. is that you're a person, but you're also operating in a collective, and you're working for the collective interest. You have to balance all those things. But to your point, our district is very diverse and very progressive, so I'm fortunate to feel very aligned with the values of our district and what we believe in. Many of us believe in having a better environment, having access to health care, affordable housing, ending systemic poverty, fully funding public schools, and ending mass incarceration. My platform is what I believe in. I didn't morph my platform to fit the district. I ran on what I believed was best for me and best for our district, and that resonated with people. So I actually feel like I have a lot of ability to vote my values and vote the values of our districts.

Of all the legislation you’ve gotten to co–sponsor and lead yourself, what is the one you’re most proud of so far?

The thing you realize about a lot of legislation is a lot of it is this stuff that might not necessarily sound sexy, but is actually extremely important. This bill is a really simple change, but it could have some pretty important ramifications. The bill is HB 1475, which is a bill that allows minors to access their birth certificates. YEAHPhilly, an organization that does advocacy work with at–risk youth in our community, came to me with this issue. They mentioned working with a lot of young people who run into this issue where they might be trying to seek employment, or they might be trying to find benefits while with a social services organization, but they struggle because they can't access their birth certificates. You have to have parental or guardian consent to get your birth certificate, so if you're estranged from your parents, or if you're in the foster care system, that can be a barrier to getting that document, which can stop you from getting employment. It was clear that this was actually preventing a lot of young people from gaining employment or access to social welfare, which then obviously can push them to commit needs–based crime or not be able to get the things they need to take care of themselves. So we took that and created this bill that removes parental consent and lowers the age you're independently allowed to get a copy of your birth certificate to 12 because that's the age you can get your social security card. I really like this one because of what it represents in terms of who we're serving, the fact that it came from an organization based in my district, and that it's a relatively simple fix.

What are the biggest challenges you face as a progressive in the state house?

I think one of the big challenges I've been wrestling with is not having as much of a coherent strategy around how to push legislation. Philly is lucky; we have such progressive champions. We have Helen Gym and Jamie [Gauthier] and [Malcolm] Kenyatta and a city council that is the most progressive it's ever been. We have a lot of organizations that are doing the work on the ground around local city politics, and it's resulted in us having some pretty big wins over the last few years. But we don't have the same kind of organizational infrastructure when it comes to Harrisburg politics. It's challenging, because Harrisburg is responsible for so many things. So, for example, looking at public education, Pennsylvania received $7 billion as part of the American Rescue Plan. And it was the legislature's responsibility to figure out how to spend that money. Obviously, our schools have been underfunded by millions of dollars, so there was an obvious opportunity to spend that money on public education in Philadelphia, and we didn't. That's because the legislature didn't do it. We still haven't figured out a coherent plan around how to hold the Republican leadership accountable for that. So it's challenging to not have as clear of a strategy on how to navigate those campaigns.

As we look towards the future, what are some of the highest priority issues on your agenda right now?

Spending the American Rescue Plan money. That’s it. Republican legislatures put billions of dollars into a rainy day fund. I think everyone should know about that, and should also know that there's literally billions of dollars in federal funding that [have] not been spent.

How, if at all, do you work with both moderates and Republicans across the aisle to pass timely legislation?

It's the same principles you have to take when you approach organizing. When you're organizing and building a base of people, the people you talk to while knocking doors aren't going to 100% align with you. How could they? They're strangers. So your goal as an organizer is to meet them where they're at and connect on the issues that you both care about and use that to move people toward a campaign. It's the same principles for my colleagues. I may not agree with all of the people in the caucus or in the party, but I can find things to agree with them on education, around the environment, around health care, around the minimum wage and workers' rights. And I think focusing on that—versus the differences—goes a long way for me because I don't have to feel like I'm compromising myself. I'm still being very clear about my long–term vision heading into the conversation, but I'm focusing on the things we can do right now. People will respect that. People that are really getting things done and are trying to lead just want to work with other people that want to get things done.

Is good legislation primarily innovative or practical? How do you balance the two?

I think it can be both, or one or the other, depending on the context. I try to be pretty pragmatic in thinking about legislating. I don't say that to sound like an incrementalist, but I think that one of the balancing acts we have to do—particularly in chambers that we don't control—is being clear about the long–term vision that we have, whether we're progressives or socialists. I'm a socialist. I'm an abolitionist. Those are things that I hold true, but I also recognize that Pennsylvania is light years away from becoming socialist and abolitionist. So I have to be clear about my long–term vision, while also thinking about the building blocks toward that vision. Those involve passing things that can be done now and do matter now. You kind of have to operate on separate plans of playing the short term to get things done, while also figuring out what's the long–term chess you have to play to get to the future.

Taking into account the relative privilege we have as Penn students, what’s your advice to incoming first–year students about how to be a good neighbor?

Step one to being a good neighbor is just to be a neighbor. That's difficult for a lot of young people in general. Often, I think whatever insecurities or anxieties you feel about being part of the community become projected. The truth is that, yeah, people are concerned about gentrification, but you are not responsible for gentrification. [First years] are not responsible for gentrification, or unfettered development, or rising property taxes. Penn buying up tons of properties and not being equitable in their development is responsible for gentrification. So in terms of being a good, responsible neighbor, I think it's just about doing what you would do in any other community. Get to know the people who live on your block, go to neighborhood association events. Just be a regular human being. Do the things you want to do and feel comfortable doing, and be someone genuinely rooted in the area—not just because you think it's the right thing to do, but because you care about West Philly.