Three professors to over 4000 undergraduate and graduate students. That was the ratio of core faculty in the Asian American Studies (ASAM) Program to Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI) students at Penn in 2019. That same year, there were 248 tenure–stream AAPI faculty at Penn—the vast majority of whom didn't specialize in ASAM—compared to nearly six times that number of white tenure–stream faculty.

In the 25 years since its inception, ASAM at Penn has withstood countless threats to its faculty and resources. The current battle to prevent the departure of David Eng, Richard L. Fisher professor of English and one of ASAM’s three core faculty members, is nothing new. It’s the culmination of decades of disregard for Asian American issues from the Penn administration, in a society where Asian American identity and history is often ignored and erased.

As Asian Americans face an uptick in hate crimes and continue to struggle for visibility alongside other underrepresented groups, ASAM at Penn is uniquely positioned to provide students with a community that extends beyond the classroom.

Yet Penn has a long history of dismissing student concerns and devaluing Asian American issues. The story of ASAM at Penn is one of tenacity, protest, and solidarity: Together, ASAM’s students and alumni have spent their entire academic and professional lives fighting to be heard.

ASAM’s current standing faculty consists of three people: Josephine Park, director of ASAM, professor of English, and undergraduate chair of the English Department; Eiichiro Azuma, associate professor of history; and Eng. Fariha Khan is the associate director of the program and has taken on the burden of many of the program’s administrative responsibilities. Most recently, Eng announced his potential departure, citing a lack of institutional support for ASAM as a catalyst.

David Eng teaching "Introduction to Asian American Literature and Culture" in a classroom in Fisher Bennett Hall. Photo courtesy of David Eng

This has ignited massive concerns around the state of ASAM and its faculty.

As a program and not a department, ASAM is unable to hire its own faculty. With such a small number of professors and administrators, ASAM simply doesn’t have the capacity to provide students with the classes and resources they need.

“We’re going back 30 years, if we don't do anything about [the program’s decline in numbers],” warns Kate Lam (C ’92), who helped raise concern over the lack of Asian American representation in Penn’s curriculum when she was a junior at Penn.

In February of 1990, Lam and her fellow students in Students for Asian Affairs—the predecessor to the Asian Pacific Student Coalition (APSC)—organized to demand a program in the College of Arts and Sciences that featured Asian American identity and history. Starting as a single weekly lecture, the program took six full years to come to fruition.

In the fall of 1999, the APSC united various campus and constituent groups to launch a rigorous campaign—including petitions, rallies, and a proposal submitted to the University president—that would eventually lead to the creation of Pan–Asian American Community House (PAACH), the cultural center for Asian students at Penn.

From 2003 to 2009, the program expanded under then–director Grace Kao, who helped fight for a space for ASAM in the McNeil Building. In March 2008, already lacking full–time staff members, the program received unexpected budget cuts. Thanks to student activism and Kao threatening to resign, the proposed budget was revised, but this close call would be far from ASAM’s last brush with extinction.

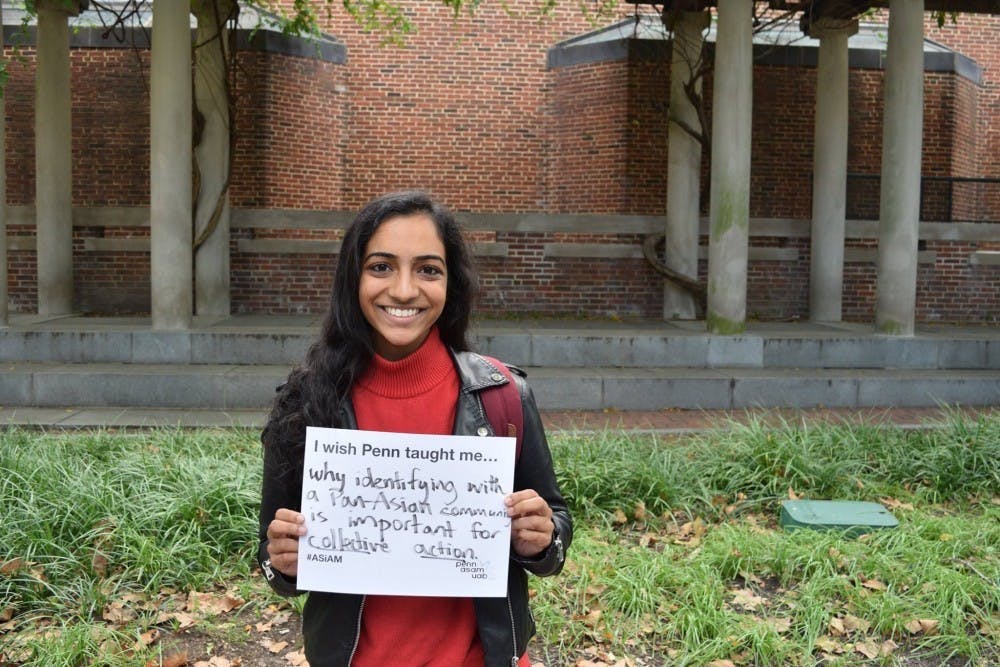

In January of 2017, Grace Kao left for Yale University after over two decades of service to the Asian American community at Penn. Her departure incited a new wave of student advocacy that included protests on College Green, an open forum, three separate emails to School of Arts and Sciences (SAS) Dean Steven Fluharty, and a petition that garnered over 1,300 signatures. The ASAM Undergraduate Advisory Board (UAB) also launched a #ASiAM campaign to collect student testimonials.

Natasha Menon for the 2018 #ASiAM campaign, Photo by Luke Kertcher

Seung–Hyun Chung (C ’18) helped organize the student response to Kao’s departure. He describes his experience meeting with the SAS dean in 2017: “It felt dehumanizing. I felt embarrassed that we needed to talk to these deans who had no understanding of why this was important to us. And we had to do that for every semester.”

Now, students and alumni are using similar organizing tactics in the fight to retain Eng. “The joke we’re making now is that if we need to write another letter in the next four years, we’re just going to copy and paste the last one,” Chung says. “Because this shouldn’t be happening constantly, and yet that’s how much of a non–response we’ve had.”

In 2018, it took over four months and multiple follow–up emails for the ASAM UAB and Azuma, who was serving as ASAM's interim director, to hear the deans’ response to their demands. The verdict: no to more tenure–track faculty, no to more administrative help, no to more physical spaces for talks and events, but yes to one full–time lecturer who could teach two courses for a maximum of three years.

Now it’s 2021. The University has made no progress on the search for an interim ASAM director. Park, the program’s official director, plans to go on leave for the 2021–2022 academic year. If Eng leaves, Azuma will be the program’s only tenured professor in the upcoming school year. Students, alumni, and faculty have retraced familiar steps to protect the program—a petition, statements and op–eds in The Daily Pennsylvanian, and meetings with the dean.

But this year’s battle feels like it has higher visibility, with 58 faculty members joining the over 800 students and alumni petitioning in support of ASAM and the retention of Eng.

Six of the eight members of the ASAM Undergraduate Advisory Board. Photo courtesy of Claire Nguyen

Though English is his home department, Eng is also a core faculty member in ASAM, the Comparative Literature and Literary Theory Program, and the Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Program. Eng reflects on his time at Penn as he considers leaving the University to take a professorship elsewhere.

“Fourteen years is a long time to try to build something,” he comments. “Honestly, you just get tired, and then you get these other opportunities.”

These opportunities come from places like Harvard, which appear to be prioritizing the expansion of their ethnic studies programs. Ultimately, Eng’s departure hinges on whether or not Penn hires his partner, a law professor at Emory University. This practice is not unusual in academia, as the English Department alone already has around eight heterosexual couples.

Eng is popular among students, even winning Street's title of one of Penn’s most beloved professors in 2015. During the fall semester, his class “Introduction to Asian American Literature” was the most highly demanded class in the English Department.

Over his time at Penn, Eng has devoted himself to unlocking student potential, helping to recruit countless doctoral students as the former graduate chair of the English Department and training over 40 graduate students in total. Ultimately, Eng recognizes his duty as a professor is not only to introduce students to new bodies of work, but also to provide students with representation.

“Part of my responsibility as a person of color, as a gay person, is to model identity. It's ultimately so important to have students of color see a professor in front of the room who looks and reflects and knows their history back to them.”

Like many of his current students, Eng is a child of Asian immigrants. He knew nothing about Asian American studies until he discovered the field during his graduate study at the University of California, Berkeley, which he only thought to pursue thanks to the encouragement of three female faculty members who noticed his potential as an undergraduate.

“I wouldn't be a professor today if it hadn't been for those three women who invested in me,” he says. “A lot of [issues about race and representation] get so politicized, but on another level, it's simply that there's a whole slice of the population who isn’t allowed to fulfill their potential.”

Inside a meeting with ASAM students. Photo courtesy of Claire Nguyen

The loss of Eng is especially painful given the relevance of his research on the social and psychological struggles of Asian American college students. In his 2019 book Racial Melancholia, Racial Dissociation, Eng and psychotherapist Shinhee Han examine how Asian college students are affected by the model minority myth and colorblindness, which create the perception that Asian Americans are raceless and self–sufficient. The racial roles played by Asian Americans in American history—whether they be targets of racism and xenophobia or agents of activism and solidarity—are erased from most school curriculums.

Simply put, in the story of race in America, Asians are invisible.

“The model minority stereotype makes Asian Americans adjunct to whiteness,” explains Eng. “When universities don't want to give Asian Americans resources, they say they're just like white students. They have no problems, they do perfectly, they're just white, they can just take white classes. And the moment that [Asian American students] start to make demands, that's when the administration suddenly feels the need to take a step back.”

The phenomenon Eng describes comes at a major psychological cost. Without the tools or knowledge to contextualize their place in American society, Asian American students struggle with feelings of alienation and loss, regardless of how externally accomplished they may be.

The model minority stereotype contributes to the invisibility and neglect of Asian Americans’ mental health needs. AAPI college students are least likely to seek help for mental health, and are most likely to identify with feelings of hopelessness, depression, overwhelming anger, and suicidal ideation.

As increasing rates of anti–Asian violence garner international attention and college students face additional mental health burdens due to the pandemic, the need to provide Asian American students with sufficient psychological and social support is urgent. Penn’s Task Force on Support to Asian and Asian American Students and Scholars (TAASS) was intended to provide psychological support to students, staff, and faculty affected by anti–Asian racism. However, Yuhong He, one of the three Asian members on the task force and the only representative from Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS), left Penn in August of 2020 and was never replaced. The list of members of the task force, which has not been updated since June 2020, still lists her name. There have been no new programs since March.

“I am so tired of only being seen and cared for when I'm sad, or angry, or upset,” says Claire Nguyen (C '22), the current co–chair of the ASAM UAB. “I feel like I'm constantly being tokenized or a burden for requesting having spaces on campus for Asian students, when the University should just have spaces for all students on campus.”

ASAM has the potential to help heal the emptiness and alienation Asian students experience by directly focusing on the unique challenges of being Asian American and teaching students, in essence, how they belong in America.

“[ASAM has] really given me a critical language to be able to describe a lot of experiences that I've encountered personally and that I've seen elsewhere in my life of racism. Being able to put that language within a systemic framework has been so important to my understanding of how white supremacy operates, particularly in the United States,” says Erin O’Malley (C ’21), the other co–chair of the ASAM UAB.

Yet both alumni and current students involved with the ASAM UAB describe unusually high levels of burn–out and exhaustion, which they attribute to a lack of progress and a feeling of not being heard.

When asked about potential burn–out of student leaders at Penn, Associate Vice Provost for Equity and Access Rev. William Gipson comments, “As administrators at the University, we want to know how we support students—what is it that you need from us to help you to reach your goal? What we're encouraging is real conversation, interaction, and engagement.”

On March 30, 2021, Fluharty announced that SAS would undertake a search to fill multiple standing faculty positions in ASAM for the 2022–2023 academic school year. Though the two events—Eng’s potential departure and the College's plan to fill multiple standing faculty positions in ASAM by 2022–2023—technically have separate origins, the proximity of the two announcements has not gone unnoticed.

“[My] first thought was: fantastic. Let's give credit where it's due. It is a response,” says Lam. “But the second thought is: It's pretty reactive. And the third thought is: What's next? What are the executable plans? Who are the stakeholders? What accountability lines do we have?”

ASAM’s exhaustingly cyclical history—lose resources and people, engage in rigorous student–led activism to regain what was lost, receive an unsatisfactory response, and repeat—sheds light on why students, alumni, and faculty feel so skeptical about the recent announcement.

“This cluster hire feels like a compensatory gesture, because if they lose Eng, there’s only two faculty members left. And if they try to hire three more, that’s just plus one to [the four] we originally had [in 2017]. It’s a bandaid to the outrage that students and alumni have,” adds Chung.

With Park taking a sabbatical for the 2021–2022 academic year, there will be no director for ASAM—and therefore very few scholars with any expertise to actually lead the search.

Students and alumni are also concerned that once media coverage of Asian American issues dies down, any hope for the program’s expansion will be lost. Paulo Bautista (W ’14), who was heavily involved in PAACH and Asian student organizing at Penn, explains the structural problem he sees in the University: “The administration knows that students have a lifetime: four years, and then they matriculate. Basically, they wait it out until there are new students who don’t understand the issues. That’s where we the alumni with our institutional history come in.”

Students and faculty protest on College Green in support of the Asian American Studies program following Grace Kao's departure in 2017. Photo by Haley Suh

Throughout ASAM's struggles to survive, the institutional knowledge shared between Asian student leaders has highlighted the program’s strengths. “ASAM has always been really good at mobilizing, and that sort of historical legacy isn’t something that all the different ethnic studies programs have,” says Erin.

Erin is right—in 2015, Penn’s Africa Center closed, and the African Studies Program (which focuses on African diaspora) later merged with the Department of Africana Studies (which focuses on the African continent). Penn also currently doesn’t have a single standing faculty member in Native American and Indigenous Studies.

The survival of ASAM can mean hope for all ethnic studies programs at Penn. Throughout its history, Asian American studies has played a significant role in promoting social justice and encouraging coalition–building with other marginalized groups. In fact, the term ‘Asian American’ was coined by university students in 1968 to strengthen the multi–ethnic coalition that fought for the first ethnic studies programs. In many ways, one of the highlights of the history of ASAM at Penn is the continued passion and persistence of students despite numerous institutional barriers.

“We should be locking arms. Our experiences are worth being represented, and studied, and understood. Whether you’re Black, or [Native American], or Asian, all of these things need to be interwoven,” says Ben Huynh (W ’14), current president of the University of Pennsylvania Asian Alumni Network (UPAAN).

“There is a side of learning that is about academics, and there's a side of learning that is about self–development, and there's a side of learning that is about saving the world,” says Eng. “That, to me, is the very definition of what makes ethnic studies and women's studies so different in the academy—because these are fields that were formed in relation to social justice and social protest.”

Additional resources for Asian American students:

Asian American Psychological Association

Asian Mental Health Collective

Chinese Immigrant Family Wellness Initiative

Counseling and Psychological Services

List of AAPI Therapists in Greater Philadelphia

Reduced Fee Therapy and Support for Asian Americans