“You took the space from a good man.”

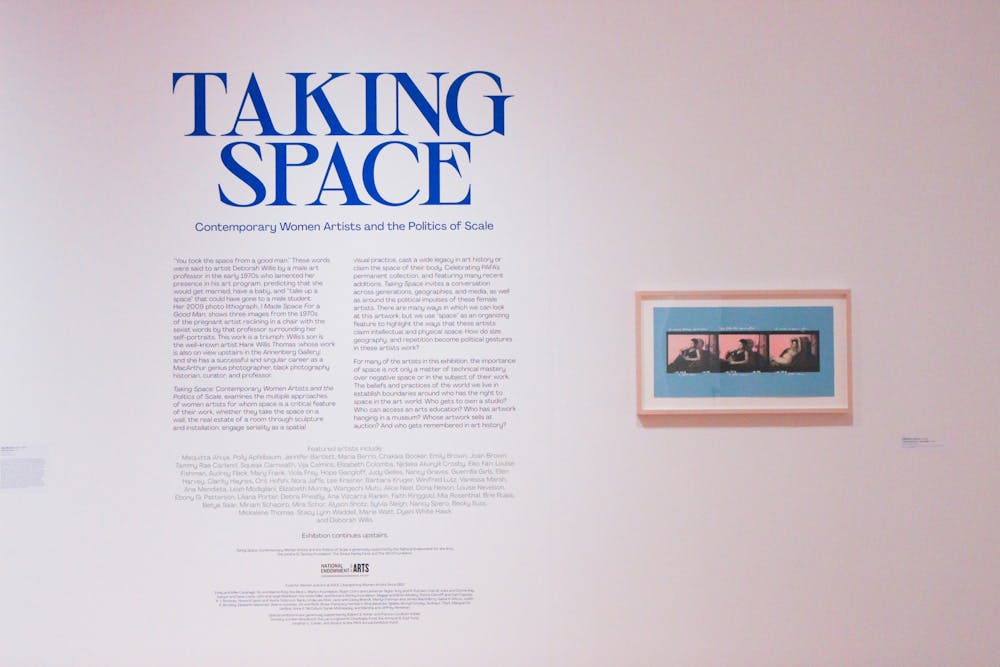

These words frame the “Taking Space: Contemporary Women Artists and the Politics of Scale” exhibition in the Samuel M.V. Hamilton building at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. The quote refers to a comment from Deborah Willis’ male art professor in reference to her presence in his early '70s classroom. It encapsulates the challenges of female existence within the art world and beyond. Made by women of entirely different decades, identities, and backgrounds, these works are unified by the central theme of space—either in terms of their large scale, or thematic and symbolic meanings. These five pieces are just a taste of what this expansive exhibition, lasting from Jan. 21 to Sept. 5, has to offer.

Joan Brown’s Self Portrait, 1977 uses thick cartoonish lines and flat planes of solid color. It shows the artist in her workplace, a space that is sacred and dedicated to her creative expression. Her decision to depict herself while painting places her among famous female artists throughout history, who also represented themselves as working in self–portraits. These artists, like Artemisia Gentileschi or Joan Brown herself, seem to assert their artistic identities by providing visual evidence of their skill—almost as if they feel a need to prove they can paint in a field that continually questions their ability.

As a caricature of the female artist stereotype at the time, Brown panders to the public's expectation of her by painting herself seated daintily with her legs crossed, wearing a stylish dress with stilettos. Within the image, Brown is shown painting a simple and tame still life. This differs greatly from her typically involved and interpretative style, making the polite, mild–mannered version of herself in the self–portrait stand out even more.

Mequitta Ahuja’s A Real Allegory of Her Studio gives viewers a different window into the female artist’s workspace. This intimate and personal scene includes a woman of color sitting with her back turned and books of images surrounding her, which she looks at contemplatively. The figure in the open publication balanced on her right knee echoes her exact position: cross-legged with a book in its lap. The bottom right corner of the painting resembles a curling page, almost as if the image itself is a page in one of the books the central figure is engrossed in.

The presence of this curling paper as well as the multiple planes of color and unclear outlines add to the deceptive and paradoxical nature of the painting, prompting the viewer to think critically and draw their own conclusions. The viewer is forced to contemplate what exactly they are seeing, and, more importantly, what the painting's elements mean. This space is extremely allegorical, as the title suggests, for the artist in the painting is in a piece of art, around art, and a creator of art herself.

Diving into questions of youth and blackness, ...doing what they always do…(...when they grow up…) by Ebony G. Patterson is a strikingly critical installation. Made of woven tapestry, beads, glitter, toys, balloons, and more, the piece evokes feelings of fun and silliness. Underneath this innocuous façade are images of Black youth, included in an effort to emphasize their innocence in the face of systemic racism. By aligning Black children with youthful playfulness, Patterson forces viewers to think about their systemic loss of innocence, whether as a result of police brutality, legal injustice, or general discrimination.

Acting as a visual reclamation of youth, the piece is covered with punctured holes to suggest violence, trauma, or even bullet wounds. Alluding to the murders of Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, and other Black victims, the fact that Black boys are 18 times more likely to be tried as adults in court than their white counterparts, and the growing list of missing young Black women, Patterson exposes social dichotomies between youthfulness and Blackness.

Riding Places by Elizabeth Colomba subversively places a young Black woman within a space many believe she should not occupy. Beside a bucking horse and in front of an impressive estate, the luxuriously dressed central figure in this watercolor composition stands with an aristocratic air. The artist’s own experience with her French and Caribbean identities has motivated her to “reshape narratives and bend an association of ideas so that a Black individual in a period setting is no longer synonymous with subservience and, by extension, does not instill fear or mistrust.”

To construct this alternate vision of history, Colomba utilizes classical canons of European art as well as a strict technical framework. The image is rendered with impeccable attention to detail, using realism as a tool to reconstruct the viewer’s conception of reality in a racially controversial yet poignant manner. By placing a young Black woman within this scene, Colomba twists the past to realign her with luxury and power rather than powerlessness and inferiority, ultimately transforming the social space she occupies.

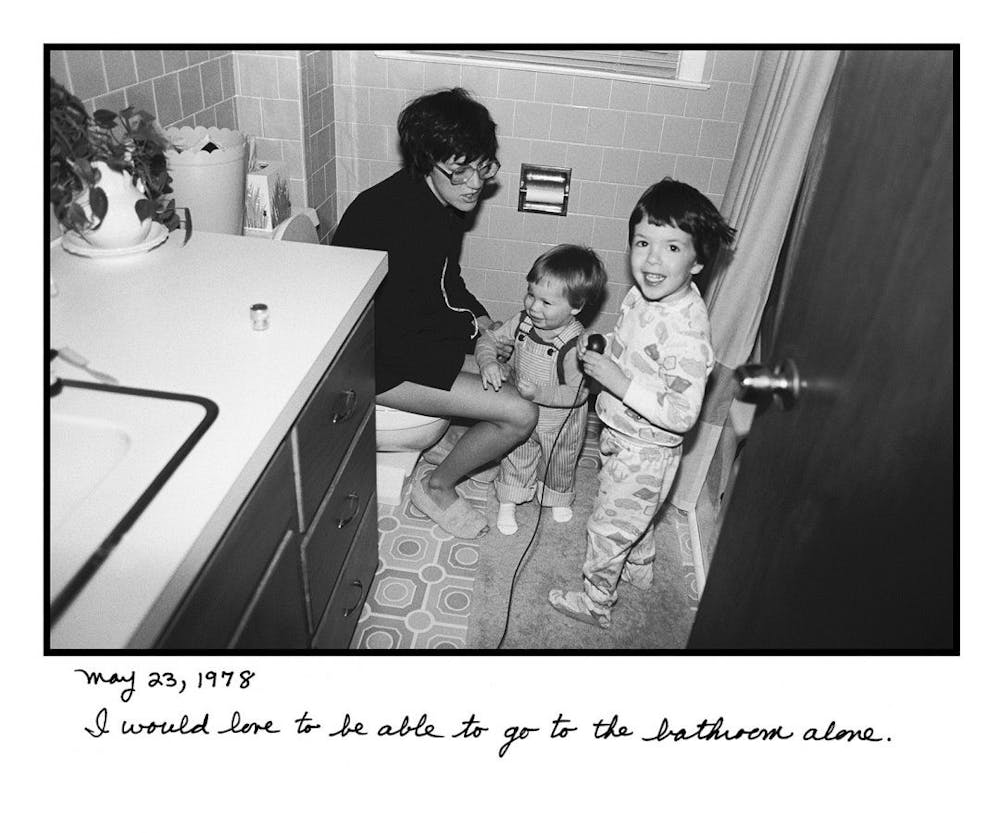

For Judy Gelles, personal space is a precious commodity. Documenting parts of her journey through motherhood in the late '70s and early '80s, her Family Portrait photo series captures the ups and downs of parenting with humorous script captions. The series demonstrates Gelles’ transformation of her home—a space full of diapers and toy trucks—as seen in Living Room June 10, 1979, into a creative, studio–like space. Consumed by the responsibilities of motherhood, Gelles finds solace in the little moments, which she communicates to viewers by offering them a glimpse into her home life.

In Bathroom May 23, 1978, Gelles’ two young kids crowd her even as she uses the toilet, and in Self–Portrait Watching the Soaps March 3, 1979 she takes an “hour and a half” to herself. Tackling subjects like shared, personal, and messy space, Gelles shows that balancing the demands of domesticity has its ups and downs. Like she is flipping through a scrapbook and explaining each moment to viewers with a gentle smile, Gelles has imbued the series with a tender, homey quality.

The exhibition commemorates the 100th anniversary of the 21st amendment’s ratification, which granted women the right to vote. Given the socio–cultural implications, this exhibition is a must–see. Its diverse discussions of space represent women of vastly different backgrounds, identity groups, and worldly views. While these artists take space in their own ways, one thing is certain: You should definitely be 'taking space' at this exhibition as soon as possible.