My days have softened into routine. The gleaming novelty of dining hall food, snow, and independence has slowly drifted away. Curled up on my twin XL bed, you can find me reading the weekly novel assigned for my most unconventional class this semester, "Happiness and Despair." This week, James Baldwin’s narrative makes me fall in love with Giovanni’s Room. One quote is especially significant: “Perhaps home is not a place, but simply an irrevocable condition.”

Across the room, a virtual pile of prerecorded lectures accumulates while I miss the familiarity of home. I’ve never been worried about feeling homesick, and I didn't think college would be any different. However, I now realize homesickness might be real. Back home, I counted down the days to come to Penn, to gain the autonomy I had been longing for. Yet now that I am here, I can feel home’s gravitational pull.

Being in such close emotional proximity to everything you thought you were ready to grow away from feels absurd. I'm a nostalgic at heart. Everyday old memories bring me comfort: my mom’s discursive style of talking about news, the fireplace lighted by my dad every morning, and the coziness of my own bed. Since homesickness is mainly sentimental, I even brought some physical things with me when I moved in: my high school’s sweatshirt, old family pictures that I put up in my dorm, and a collage of tickets to Madrid’s museums and concerts that now sits on my wall.

Perhaps Baldwin is right. Home has started to feel more like a condition. The vivid greenness of the backyard grass, the pebbled sidewalks around Madrid, dinner at 10 p.m., and my everyday siesta. Filled with Spanish stereotypes, home feels like a voice softening with distance. And, as if floating, you feel like this place does not belong to you anymore. It exists just to be loved, missed, and yearned.

Predictably, most of my homesickness comes from food and how nurturing it is. Because it's an important part of our culture, I miss Spanish olive oil and my dad’s signature breakfast—a piece of toasted bread with freshly grated tomato rubbed over it. I miss the bright and harsh sun and seeing people drink beer in the cold, even if it's two degrees Celsius—or, gasp, 35 degrees Fahrenheit—outside. I miss traditions that currently exist an ocean away, rooted in the comforting scent of a late dinner on a summer night.

But above all, there is something that comes with such familiarity that I cannot escape. Back home, eating is inherently social. Sobremesa does not have a clear American translation. Its literal meaning is "over the table." It's the experience of sharing food and the conversations that come after it. Food is so central to Spanish society that it affects our social structures.

My family, gathered around a paella every Sunday. A Saturday afternoon spent at a bar, surrounded by friends. An after–class lunch, always accompanied by some great jokes. The intimacy that timidly lingers between the moment when the dessert comes and the time when the bill is paid. Usually, there’s laughter involved, although it's during this talkative time that we have the most ferocious arguments. It’s through these emotional sobremesas that social bonds are created.

Eating in the United States feels lonely. Not that I don’t have anyone to share food with—right now, I'm blessed to have found great friends with whom to share Hill House's Caesar salad and 1920 Commons' tater tots. We walk along Locust, visit Penn Park, and enjoy the times we get to explore cuisines around Philadelphia. I have people to eat with, yet I mostly do it alone. It might be a college thing, but oddly, I now cherish eating in company more than ever.

An American might ask what made me leave the country of sobremesas. Why am I here in the first place?

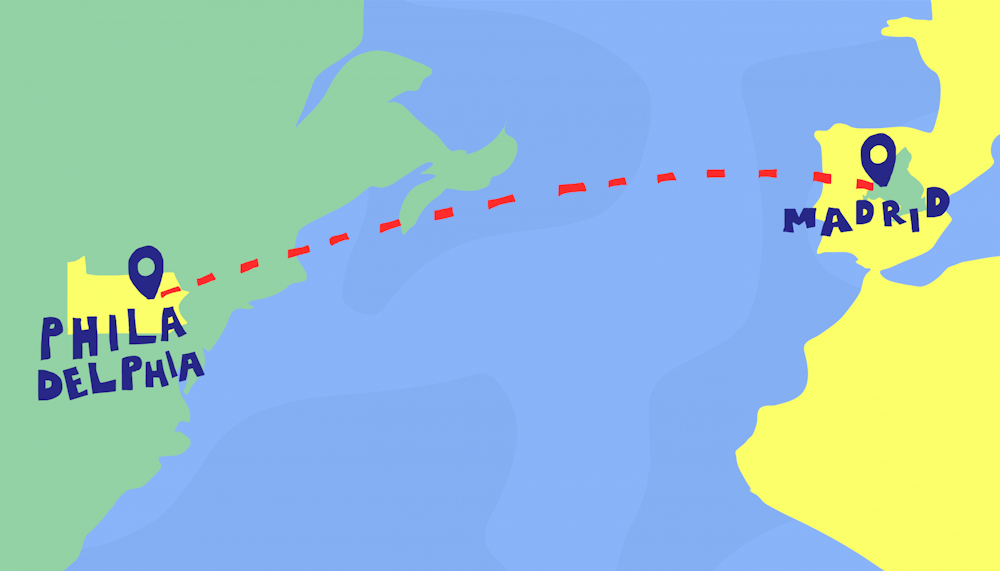

In a year of isolation, it's almost comical how the word 'homesick' means the exact opposite of what it seems to mean. It sounds like, "feeling sick of home, bored from being at the same place for so long, and in need of a change of scenery." Have we not all experienced this? As much as I enjoyed living in Madrid, I could not wait for the plane to take off. Living at home during the fall was a constant reminder of the privileges I have—access to online classes, a supportive family, a home—and what I lacked—mental stability, morning classes, endless sobremesas with new friends.

And thus, here I am, exploring the beauty of American life. Although I was familiar with the United States and its people before moving here, I have found a campus (or perhaps, a country) where everything appears to be coated in calculated layers of norms: Fahrenheit instead of Celsius, inches instead of meters, $1 bills instead of 1€ coins. A culture that encourages a very specific set of values: optimism, drive, attentiveness, grit. The eagerness to be innovative, even if unsuccessful. The mindset that not all those who wander are lost.

That is why I came here. To expand the sense of belonging that I felt the first time I visited the United States. To continue being surprised by strangers that engage with me in small talk in the most genuine and candid way. To still not understand how Fahrenheit works. To become part of a multicultural space. To experience the spark in a Penn student’s eyes that tells me they want to change the world. To be the owner of my own education. To build my future brick by brick, interweaving poetry, health care, and whatever it is that I discover next. I came to Penn to engage in meaningful conversations, sobremesas, or whatever one wants to call them.

I am eager to blend my colorful and vibrant Spanish heritage with American diversity and opportunity, intertwining my two life experiences. While I now have a ritual of eating scrambled eggs and turkey bacon on Sunday mornings, I will always make time for my friends to understand the importance of gathering around the table. I will enjoy my very early dinners, and I will admire my beloved Spanish painters at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

It's been a full month since I arrived, and sobremesas are still on my mind. I miss raising my voice about how the answer to Spain’s political problems is not populism, but political reforms to eradicate the present corruption. I miss sharing the latest gossip among my group of friends and debating that the Spanish university system needs to change. I miss the familiarity of these conversations. But I now share my high school memories late at night when making new friends. I raise my voice to talk about how the liberal arts enable me to find myself. And most importantly, I listen, sit back, and observe the new home that I am building here.

Baldwin wrote that home is an irrevocable condition. For me, home has become an empty table at which I silently sit, uncertain which memory will come up next.