If the world’s most famous artists throughout history had Spotify, they’d most certainly be bumping Ke$ha’s “Your Love Is My Drug.” While the image of Botticelli and Dalí jamming to the track’s high–energy, glitter–infused pop beat is definitely an amusing one, it’s plausible that the lyrical message would actually have held meaning for them.

This is because many of the world’s masterpieces are rooted in intoxicating, all–consuming relationships between artists and muses. These amorous endeavors may actually have provoked the phrase, “Maybe I need some rehab.”

Birth of Venus (1485) by Sandro Botticelli/ photo courtesy of Le Gallerie Degli Uffizi

Before diving into the dynamics and psychology of these couples in general, there are a few prominent examples worthy of their own discussion. Simonetta Vespucci, known as the greatest beauty of Florence, modeled for multiple Renaissance artists including Sandro Botticelli. She is perhaps best known for her likeness in Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. Salvador Dalí, famous for his Surrealist paintings and curved mustache, was so taken by his wife, Gala Diakonova, that he often signed his pieces with both his and her names, saying, “It is mostly with your blood, Gala, that I paint my pictures.”

Famous Austrian Symbolist painter Gustav Klimt and his iconic decorative style were largely inspired by Emilie Flöge, his acquaintance of 27 years and a prominent fashionista. Poet and punk musician Patti Smith was not just Robert Mapplethorpe’s most frequent sitter but also his friend, lover, and creative counterpart. Even Rembrandt had a muse in his wife Saskia, a woman whom he loved so deeply that his entire artistic style morphed after her death. After seven years of refusing to paint with oils and instead opting for sketches, Rembrandt returned to his original medium with a new sense of sadness and grief, clearly still impacted by the loss of his beloved.

It is important to note that these relationships were not strictly defined by a male artist and female muse. A persistent stereotype exists with regard to muses, one that assumes that a male artist always takes inspiration from a mysterious, pensive, and alluring woman. While male muses were less frequent, female artists also found muses in their boyfriends, lovers, and even husbands. One such example is Marie Laurencin, a Cubist inspired artist who became romantically involved with poet Guillaume Apollinaire.

Heterosexuality is also not a defining characteristic of these dynamic duos. Many historians believe that notoriously volatile Italian Baroque painter Caravaggio was gay. His numerous depictions of young men as the Greek god Bacchus often held a sensuous undertone, suggesting some sort of homoerotic desire. While there are undoubtedly more examples of norm–defying artists and muses, historical and social pressures likely forced them to conceal these aspects of their identities. Ultimately, in the present, our lack of historical knowledge forces us to consider their identities as mere afterthoughts.

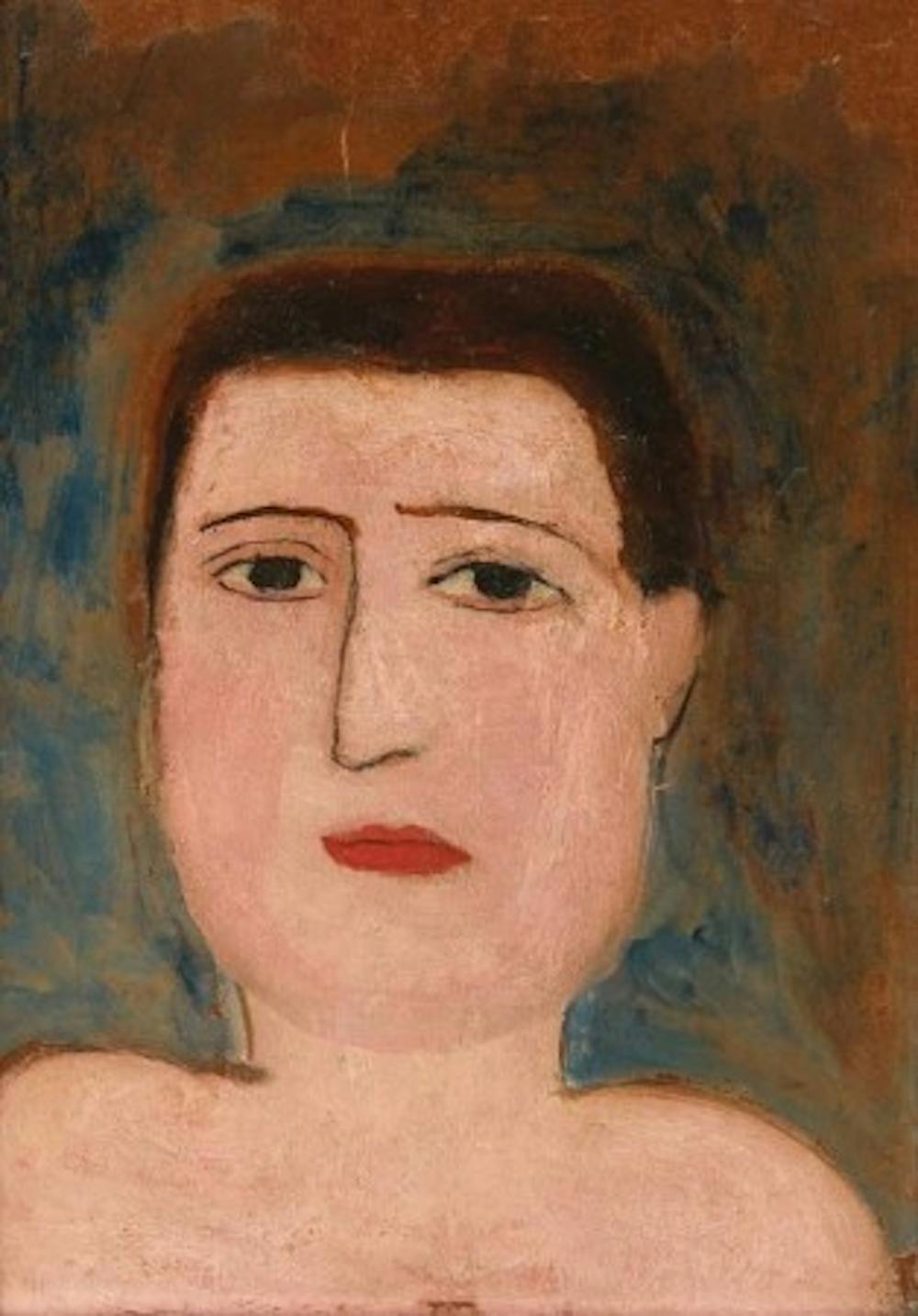

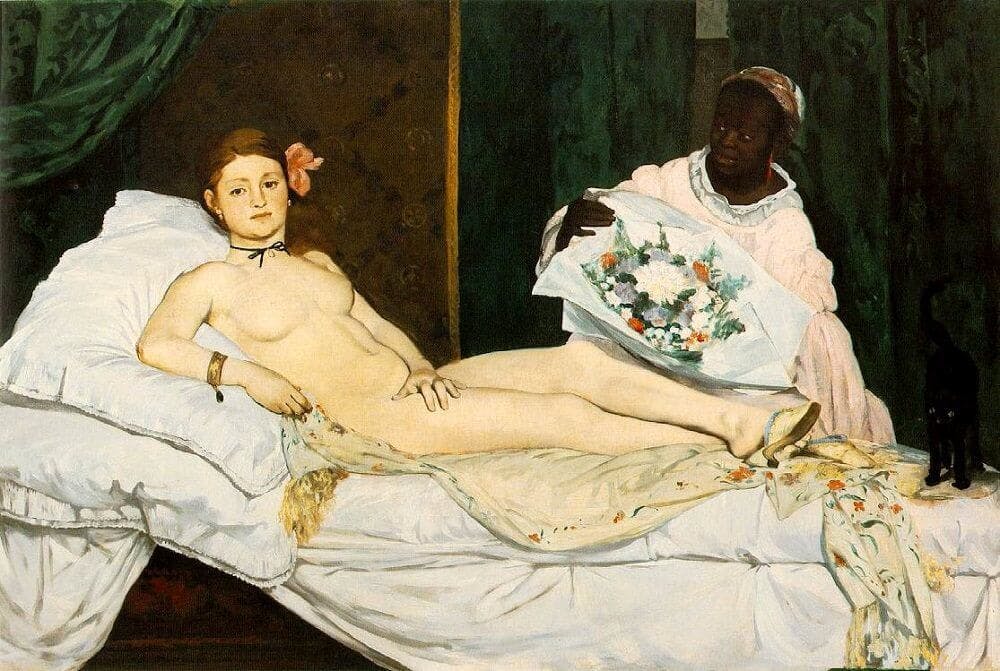

It is also not uncommon for artists to become romantically involved with one another, leading them to inspire each other. For instance, Parisian Impressionist Berthe Morisot was famously involved with Éduourd Manet, who portrayed her in Olympia and Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe. While Manet had many sitters, it is said that he was able to capture the soul of Morisot with an intrigue missing from his other images. Morisot often painted her husband Manet with their daughter, visually communicating the joy her family brought her.

While some relationships seemed to be all sunshine and rainbows, there were many more that ended in flames. Romantic and artistic entanglements are fraught with intense passion, contemplative creative processes, and even idolization, making them distinctly turbulent. The process of creating art is already passionate and emotionally involved. Combining it with infatuation and intimacy can necessitate something explosive.

Consequently, there are many pros and cons to artist–muse relationships. For starters, an affectionate relationship and artistic passion may form a feedback loop that intensifies lovelorn emotions. This can make for moving artwork and a deeper romantic connection between the artist and muse.

However, relationships like these can also go south. Much like any couple, conflicts occur. While an artist and muse relationship may be temporary, art is more or less eternal, living on in galleries, museums, and private collections. Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera are a noteworthy example of tumult in an artistic relationship—both cheated on one another extensively, divorced, and remarried. Despite the toxicity of their relationship, they continued to inspire one another’s work.

For French sculptors Camille Claudel and Auguste Rodin, years of a passionate yet extramarital relationship that inspired much of their artistry came to a ruinous end. After Claudel was diagnosed with schizophrenia, she destroyed many of her works and accused her ex of stealing her ideas, ultimately ending up in an asylum. Claudel depended on Rodin for financial support and was therefore locked into a cycle of dependency that extended beyond the intimate front.

Dora Maar and Pablo Picasso offer another clear example. As a skilled photographer, poet, and visual artist herself, Maar became Picasso’s muse and the inspiration for The Weeping Woman as well as Guernica. Maar also photographed Guernica through its creation and may have even assisted directly in painting it. Their relationship was romantic and creative but went sour after Picasso began physically and emotionally abusing Maar, who turned to painting privately for comfort.

The artist–muse dynamic is an extremely pressing topic worthy of much discussion and analysis. Understanding the psychologies, sentiments, and relationships that built some of the world’s most well–known works offers an emotional, intense, and slightly scandalous new perspective into both artistry and love.