Justin Chan (W ‘23), a Republican, doesn’t like Trump.

Justin describes himself as a more “pragmatic” conservative with liberal leaning social values. He lives in Delaware, Joseph R. Biden’s home state, and studies Finance and Business Economics and Public Policy. A few weeks ago, he voted for now president–elect Joe Biden. Justin says he cares mostly about economics and foreign policy, two issues he thinks Donald Trump has failed on.

“When I decided on a candidate, I think the one dissuading thing for me was Trump's foreign policy,” Justin says. “The 19th century wants their foreign policy back. It's so old and outdated and it doesn't stand for what America has been since the Second World War, as a leader spreading democracy and liberal values.”

Justin also mentions Trump’s erratic and irresponsible behavior in regards to the economy as a major deciding factor for his vote.

Justin is not alone as a Republican swayed by Joe Biden in 2020. Much of Biden’s appeal to highly educated conservatives like Justin hinged on his experience in government and his centrist ideology. Justin himself said, “I think Trump is going backwards, while at least Biden is staying the status quo.” With Biden in office, this comfortable middle ground seems better for some Republicans than another four years of Trump.

But, Trumpism is not dead. And despite Republicans like Justin coming out of the shadows to vote for Biden and the media frenzy that developed around the Lincoln Project, a super PAC of Republicans dedicated to beating Trump, the vast majority of the G.O.P. did not flip in this election. In fact, a greater percentage of self–identified Republicans voted to reelect the President this year than they did in 2016. Highly educated, establishment Republicans who found solace in the moderate politics and decency of Biden are now left to reckon with a G.O.P. still largely beholden to Trumpism. For young Republicans, specifically, who tend to be more progressive on issues like LGBTQ+ rights and climate change and will soon inherit the party, this questionable path forward looms large.

President Donald Trump at a rally in Cincinnati in August, 2019. Photo courtesy of Doug Mills / The New York Times.

The Republican Party was founded in the mid–1800s as a coalition of businessmen, Protestants, abolitionists, and former slaves in the North. The party was created in an effort to stop the expansion of slavery into Western territories and won the White House for the first time in 1860, with the election of Abraham Lincoln. After Trump tweeted that four women of color in Congress should “go back and help fix the totally broken and crime infested places from which they came,” House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R–CA) proudly drew on this legacy to deny Trump’s racism, reminding Americans that the G.O.P. is “the party of Lincoln.” Technically, this is correct.

Despite Lincoln’s historic tenure in office, the Republican coalition became increasingly weak in the decades following his presidency. By the time Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a Democrat, was elected to guide the country out of the Great Depression in 1932, the Republican Party had almost no political support.

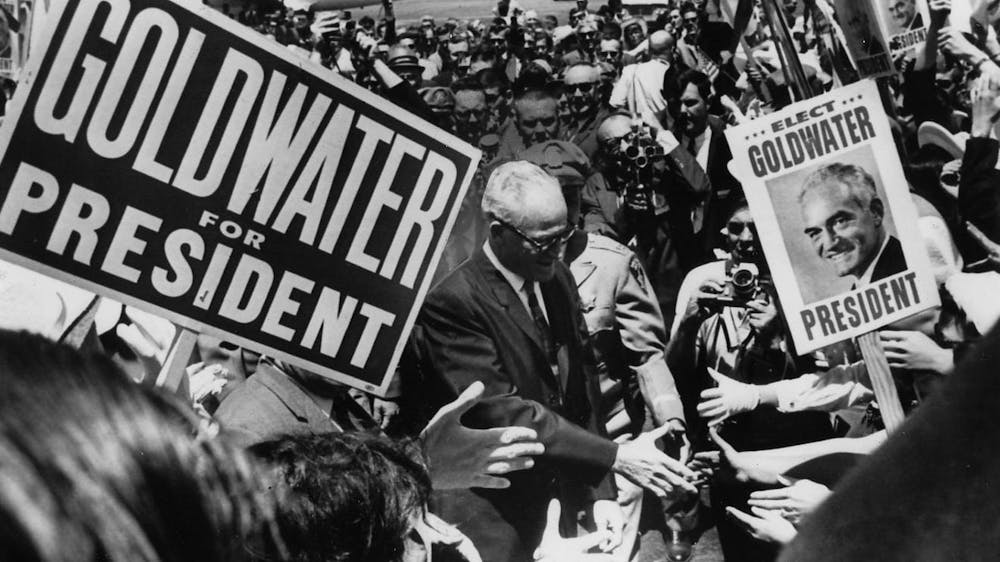

By the 1960s, however, the G.O.P. was changing following the moderate Eisenhower years. In 1964, Senator Barry Goldwater ran an insurgent campaign for the Republican presidential nomination. Goldwater was a staunch anti–communist and represented the small but growing hyper–conservative wing of the party. He voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and criticized school integration and social welfare. Despite hesitation from the prevailing, more moderate Republican leadership, Goldwater won his party’s nomination.

Upon his acceptance, he declared, “I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice! And let me remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue!”

Goldwater lost that election—by a landslide—but Goldwaterism did not. Goldwater’s anti–civil rights stance pushed almost all Black voters to the Democrats. By the 1970s, the Republican hold over the South, and white America at large, was dominant. Both Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan campaigned, and won, on similar conservative platforms. Although Barry Goldwater was too radical for his party at the time, he paved the way for party politics that would be unrecognizable to the moderate Eisenhower, let alone Lincoln.

Republicans in the post–Reagan era have been predictable: small–government, anti–abortion, nationalistic, and popular with their white, Christian, rural and suburban base. The G.O.P. dominated the South and Midwest in 1984 and 1988, and strength in those regions has continued into the 21st century. In our lifetime, George W. Bush pushed through large tax cuts, signed the Partial–Birth Abortion Ban of 2003, and sent the United States into the “War on Terror,” following the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.

George H. W. Bush after being elected President of the United States in 1988. Photo courtesy of Mike Sprague / Agence France-Presse — Getty Images.

But Donald Trump is not a predictable post–Reagan Republican. He never really attended church, never served in the U.S. military, and married three times. He has been accused by 26 women of sexual assault and paid pornographic film actress Stormy Daniels $130,000 to cover up their illicit relationship. On the 1992 campaign trail, George H. W. Bush said, “The other party took words to put together their platform, but left out three simple letters: G-O-D.” Trump’s two campaigns and four years in office had no such religious piety.

Despite all of this, Donald Trump did something right. 78% of white evangelicals voted for Trump in 2016. In 2020, polling had them showing up for Trump again in similar numbers. After months of Black Lives Matter protests, voters were drawn to Trump’s “law–and–order” messaging–a trick he picked up from Nixon. They admired his business accolades, his ability to “tell it like it is,” and his outsider status in a political system they deemed dominated by dynasties like those of the Clintons, Bushes, and Kennedys. And above all, they found solace in his racist and xenophobic messaging in a diversifying and increasingly progressive country.

Jeremy Ashe (C ‘24) is critical of Trump’s brash persona. Despite this, Jeremy says, “[Trump’s] policies are conservative, and they have been very successful.”

President Trump was never his first choice. In fact, he says if he was old enough to vote in the 2016 primary, he would not have voted for Trump. Yet, he did not join Justin and other conservatives in crossing party lines this election.

“I truly don't think that Trump's rhetoric is the best. I think it's pretty poor,” he says. “But especially for people who are young, the way I would sway them against that Lincoln Project mentality is by saying that, while rhetoric may be bad, the policies that Biden would put in place, compared to those of Trump, are significantly more harmful.”

For Jeremy, Trump’s deregulation of the economy, sweeping tax cuts, tough foreign policy against China and Russia, and nomination of three conservative justices to the Supreme Court have cemented his presidency as a successful one. He sees Trump’s economic policy as setting himself, and other young people, up for a successful entrance into the job market after graduation.

“In four years, unless you're going to grad school, you're going to be entering the economy,” he says. “The Hoover Institute had a report last week—economic growth is going to be 8% less than it can be, just because of [Biden’s] tax plans, not even including all of the new regulations that he's going to add.”

The Hoover Institute, a conservative public policy think tank, did include this projection in an October report. One of the report’s authors, Kevin Hassett, is the former Senior Advisor to the President for Economic Issues in the Trump White House.

Jeremy foresees a realignment in the G.O.P. with the end of the Trump presidency but predicts that the sentiments that created Trumpism will not fade from the limelight.

“I think the G.O.P. is going to reject a lot of this populist sentiment and you're going to see a lot more—I wouldn't say [neoconservatives] like George Bush—but you might see a little bit more like Reaganites.”

Justin, unlike Jeremy, did not remain loyal to the President in the election, but has a similar vision for the G.O.P. going forward.

“I see this very akin to the 1964 Republican Party with Barry Goldwater, extremism in the Republican Party versus the more liberalism of Richard Nixon and the establishment Republicans,” Justin says. “I think there's a fragmentation on both parties, in which the middle gap … is widening over time. With the younger generation, I think with Republicans specifically, there's actually more of a shift towards the moderate, centrist Republican ideals compared to the right wing radicalism.”

Republican Presidential Nominee Barry Goldwater greets supporters on the campaign trail in 1964. Photo courtesy of The Republic.

Justin’s prediction for the G.O.P.’s future may be correct. Stephen Pettigrew, the Director of Data Sciences at PORES, the Penn Program on Opinion Research and Election Studies, sees an inevitable realignment if the party of Trump wants to continue to win elections. Pettigrew explains that generation replacement spells out an “abject disaster” for a party with most of its base rooted in older voters. If such a party doesn’t court young votes at the same rate, their prospects look dim.

“There's good research that suggests that people's political views tend to be fairly locked in by the time they're in their mid—to—late 20s or so,” Pettigrew says. “For the Republican Party to be losing three out of four votes of young people right now—and not just in 2020, but they also did in 2016, and, frankly, going back through the Obama years, Obama did a good job of over–performing with young people—it presents a really big challenge.”

Why is the G.O.P. losing these young voters at an astounding rate? Pettigrew points to the unhinged politics of Trump that moved young voters like Justin over to the Biden camp.

And, the young people Pettigrew is talking about may have delivered Joe Biden his slim electoral victory on Saturday afternoon. More than 10 million people between the ages of 18 and 29 cast a ballot in this election, and they preferred Biden to Trump by a 25–point margin (61% to 36%). Hundreds of thousands of youth votes pushed Biden ahead of Trump in key states like Pennsylvania, Arizona, Georgia, and Michigan. Young people of color voted for Biden in even larger margins than white youth—73% among Latino youth and 87% among Black youth—proving critical in key cities like Atlanta and Philadelphia. For a G.O.P. that runs on a hyper–conservative platform that caters mostly to an older, white audience, the future looks bleak.

The bottom line, “Parties can't survive if they don't win elections,” he says. “If the party is going to survive, and it's going to want to survive, obviously, it's going to have to change itself.”

President Trump's supporters gather at a rally in Bullhead City, Arizona. Photo courtesy of Doug Mills / The New York Times.

On Jan. 20, 2021, Joe Biden will be sworn in as the 46th President of the United States. Kamala Harris will be sworn in as the first woman, first Black person, and first person of South Asian descent to serve as Vice President of the United States. This past Saturday, cities across the country, including Philadelphia, which helped decisively flip Pennsylvania for the Democrats and hand Joe Biden a victory, erupted with dancing and cheering in the streets. Philadelphia’s residents, young and old, of every race and ethnicity, rejoiced, ecstatic to see a light at the end of the tunnel once again.

But about 100 miles from the celebration occurring throughout a very blue Philadelphia, supporters of President Trump gathered on the steps of the Pennsylvania state Capitol in Harrisburg. With them, they brought rifles, protective gear, Trump paraphernalia, and above all, a stewing sense of resentment. They drove from near and far, committed to protecting the integrity of an election they saw as being fraudulently stolen from the President. Any claims of election cheating have been rebuked by all major news outlets, yet the President still refuses to accept the election results.

For Jeremy, this election marks a beginning, rather than an end. Like the protesters outside of the Pennsylvania State Capitol, he remains skeptical that Joe Biden fairly won the presidency.

“The Trump campaign, they said, if we find out that this election is completely done fairly and right and Trump loses, then he'll concede gracefully, and that's how it should be. But right now, there's too many irregularities, it seems too suspect.”

Although election counting stretched on for several days in some states due to the increased number of mail–in ballots, election monitors from both parties were present across the country and no major irregularities or fraud have been reported. Despite Trump’s loss, Jeremy is hopeful for the future of the Republican Party, and even believes that the G.O.P. was the real winner last Tuesday.

“Republicans basically won the night,” he says. “[Republicans] should keep the Senate... netted in House seats, netted in state legislators, netted in governorships, and [the Republican] base became much more diverse and encompasses a lot more people. You know, you lose the Presidency and you still win the night.” Republicans did have a number of victories on election night and Trump's support amongst Black and Latinx voters increased from 2016.

Jeremy adds, “The blue wave never came.”

Despite the victory for Biden, the landslide projected by many pollsters did not materialize, particularly in down–ballot races. In this respect, Jeremy is correct. As half the country rejoices over a Biden win, the United States will have to figure out how to govern with a Democratic White House, a likely Republican Senate, and the specter of Trump still looming over American politics. The next generation of Republicans have an even bigger question in their hands: where to push a party that is far afield from its roots, with an ever–aging base of support. If they can’t find an answer, the party may simply not survive.