It’s rare to feel yourself standing in the middle of history. Rarer still to know that you could have been a casualty. On July 5, 2009, Alim* experienced both.

This date has become a bitter memory for Uyghurs, a Muslim ethnic minority in Northwest China. But for Alim, it was simply the first day of summer. He was 17 years old, and he and his friends just finished taking their end–of–year exams. They were eating at a local cafe in their hometown of Ürümqi, the capital city of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, when rumors of a protest at People’s Square, the city’s main plaza, reached their table.

Alim and his friends decided to investigate. From the other side of the street, they watched as hundreds of protesters, mostly college students, stood in the center of People’s Square.

“All of a sudden, big military trucks come surrounding the area,” says Alim. “They blocked the road, and then military [soldiers] keep jumping off.” Police armed with riot shields, black batons, and machine guns ran towards the protesters.

There was a gunshot. Then another. Alim heard hundreds as he and his friends fled home, weaving through crowds of panicked residents. Alim saw a college student, barely older than he was, clutching his bleeding head as his friend ushered him away from the square. A string of police cars rushed past Alim as he ran. Months later, he learned that the same cars were headed to block off the road he had used to escape the square.

Now, sitting in his apartment in Philadelphia, Alim acknowledges that had he stayed at the protest five minutes longer, the police would have closed the last remaining exit, arresting him and his friends. He would have become one of the hundreds of nameless Uyghurs detained by police during and after the 2009 Ürümqi Riots, a violent eruption of ethnic tensions between Uyghurs and Han Chinese residents that left more than 190 dead. He likely would never have made it to college in the United States, where he watches the situation for his family in Xinjiang worsen day by day.

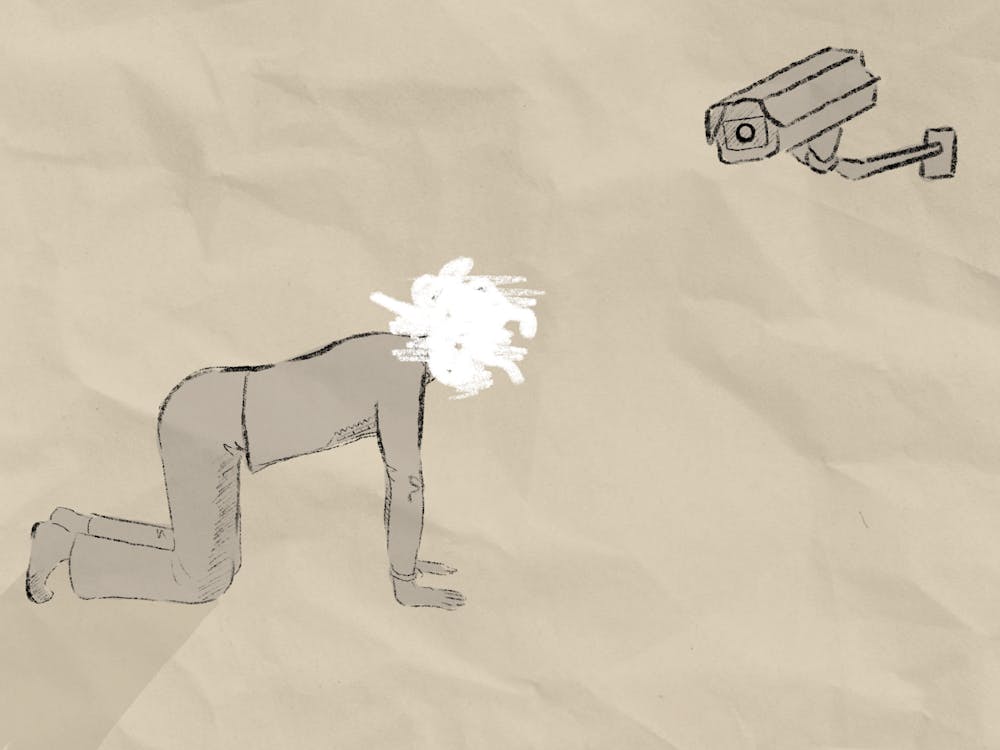

The 2009 riots marked a turning point in Xinjiang’s history. Afterward, the government vowed to crack down on terrorism, separatism, and extremism, an initiative that has now become code for suppressing Uyghur identity. The gradual erosion of the Uyghurs’ autonomy culminated in recent years with the mass internment of at least several hundred thousand and up to 1.5 million Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in “re–education camps.” Prisoners are monitored 24/7, forced to learn Mandarin and communist ideology, and punished with starvation and torture if they don’t comply.

These human rights abuses are happening a world away, yet they have a direct impact on many in the United States. Alim is one of many Uyghur college students in the Philadelphia area, three of whom agreed to be interviewed for this story. As international students under the supervision of the Chinese government, they must watch everything they do or say. Any anti–government sentiments could endanger the lives of friends and family back home, where speaking with someone abroad is considered extremism by law. All three students have relatives who were imprisoned or sent to camps. Surrounded by professors and classmates ignorant of Uyghur issues, with only a fragile link to loved ones back home, they must rely on each other for understanding and connection to their culture.

~

The 2009 Ürümqi Riots began a childhood of second–class citizenship for Mirshat*, who was an elementary school student at the time. He remembers that phone lines were cut off for days, the internet was down for months, and only one channel was available on TV. He watched the same clips on repeat: Uyghurs smashing cars, burning stores, and beating Chinese pedestrians. Local Chinese leaders called Uyghurs extremists, and the protests a deliberate attempt to destabilize the region. When Mirshat returned to school in September 2009, his Chinese teachers echoed the news, telling the class that Uyghurs were terrorists.

Lines of communication gradually reopened, but life never returned to normal. After 2009, the Chinese government doubled down on efforts to "Sinicize" the region, according to Rebecca Clothey, associate professor of education and director of global studies and modern languages at Drexel University.

“The Chinese government saw themselves improving the situation by trying to integrate Uyghurs into Chinese society by being more like Han people,” she says. Clothey points to the bilingual education policy as an example. The law, which passed in 2004 but was expanded after 2009, made Mandarin the primary language of school instruction, phasing out the importance of the Uyghur language in public life.

Other laws restricting Uyghur cultural expression, especially religion, soon followed suit. In 2014, during a year of violent attacks in Xinjiang, Chinese President Xi Jinping called for a crackdown on Islamic extremism, which he argued had spread like a virus in the region. In 2016, it became illegal for Uyghur adults to influence minors, including their own children, to participate in any religious activities. In 2017, Xinjiang residents were banned from wearing long beards or veils, common among devout Muslims.

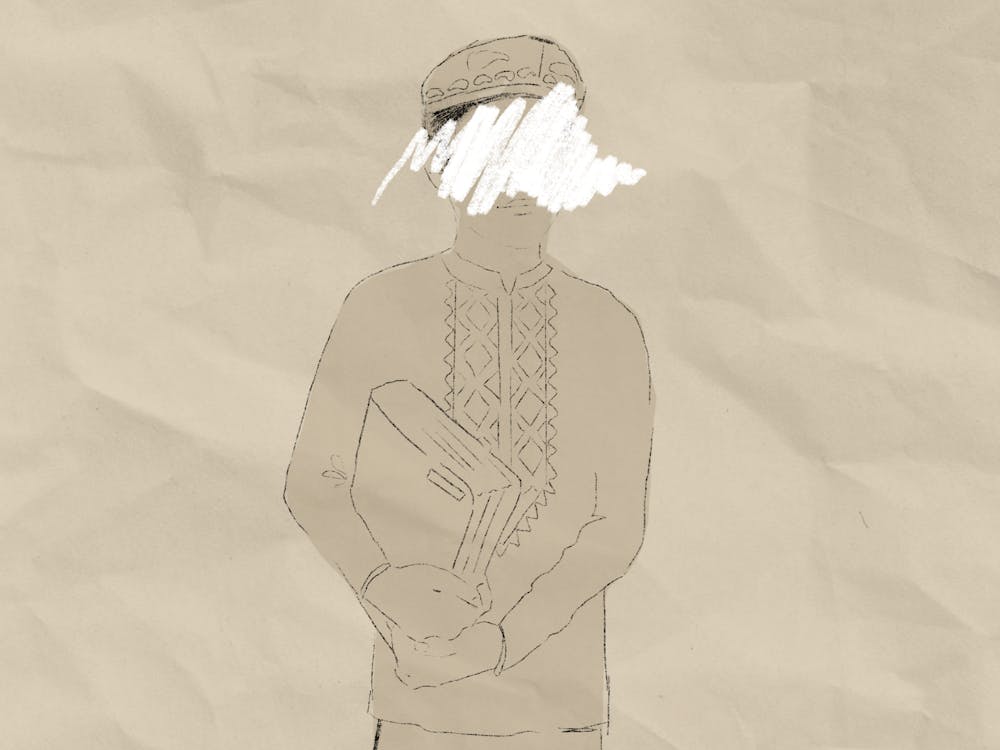

Even wearing traditional cultural clothes was deemed a political statement. Tumaris Yalkun, a Drexel student who was 13 during the 2009 riots, says she experienced blatant discrimination for the first time when she was 16. She and her friends decided to wear doppas, traditional Uyghur hats with floral and geometric designs, to school for Nowruz, a Persian holiday celebrating the first day of spring. After school–wide exercises, Tumaris says the principal singled out all Uyghur students with doppas.

“He called us out in front of the entire school,” she says. “He started yelling at us for wearing the traditional hat and commanded us to take it off. Another girl [was] recording the whole thing, and he just went and snapped the phone out from her hand.”

An increase in security was combined with these discriminatory policies, which marked Mirshat and Tumaris’ time in Ürümqi. Tanks rolled through the streets alongside cars in morning traffic. Uniformed soldiers armed with rifles kept guard at the entrance of schools. Uyghurs had to scan their IDs at police checkpoints at every bus station, grocery store, and public park, giving the state a detailed record of their movements. Han Chinese residents were often waved through without a hassle.

Uyghurs were forced to practice their faith in secret. Mirshat’s parents kept their voices to a whisper during their daily prayers, mindful that neighbors could report their religious activities to the government. During Ramadan, his family ate breakfast in darkness, afraid that police patrolling their neighborhood would become suspicious seeing a light on in the middle of the night. Mirshat says that he and his parents often had to break their fasts to avoid being discovered.

“[Companies] ask their workers to drink water during office hours so they know you’re not fasting,” he says. “If my parents are handed a bottle of water by their coworkers, they’re forced to drink it. Otherwise they’re going to get into trouble.”

Mirshat grew rebellious. He and his friends started sneaking into the mosque on Fridays, jumping the fence and avoiding the police officer stationed at the entrance.

“When I grow up, I’ll free our country,” he’d tell his mother.

“Never say that again,” she’d respond.

She would always end the conversation with the same saying: when an egg hits a stone, the egg will always crack. Uyghurs were the egg, the government the stone. The message was clear: if you go up against the impossible, you will shatter.

After a few months of sneaking into the mosque, someone on the street recognized Mirshat’s blue and white school uniform. The next day, his teacher threatened to expel any student caught climbing the fence. Mirshat never went back.

~

Mirshat’s parents were worried about him. He got into fights with Chinese kids at school. His teachers labeled him a troublemaker. He talked too much about independence. As restrictions tightened in Ürümqi, they fretted over his probable future—poverty or prison— if he remained so outspoken. They chose to send him abroad, a decision many Uyghurs have made to provide their children with a sense of freedom and a better future. Mirshat, Tumaris, and Alim all came to America for school.

Although living in the U.S. gave them more rights on the surface, the students quickly realized that their newfound freedoms came at a steep price. Voicing any anti–government sentiments—or even telling the truth about their upbringing in Ürümqi—could carry heavy consequences. Since starting college here, Mirshat says that the police have stepped up surveillance of his family. They visit his parents multiple times a year, asking for photos of him holding his Chinese ID in front of his university to verify that he’s in school.

“There’s absolutely no privacy,” says Alim, whose family has also been questioned about his studies. “[The police] can just get your phone, check all the photos, all the texts.”

Even family video calls aren’t private. Because of censorship laws in China that ban social media sites like Facebook and Twitter, citizens communicate with people abroad using WeChat, an app that is heavily monitored by the government.

“We can’t talk about politics, things that are bad about China, Uyghur history, or religion,” says Mirshat. “My parents will never say the government’s bad or communism is suppressing them, even though they can give hints.” When his parents tell him, “Our friends are coming to our house often,” he knows they mean the police.

The paranoia extends to relationships on campus, where Uyghur students say they must be careful about who they reveal their backgrounds to. The Chinese Embassy works in conjunction with Chinese student associations at various colleges, paying them money to post articles supporting the Chinese Community Party and attend welcome parties when Chinese officials visit the U.S.

“When I’m with my Chinese international friends, I don’t really talk to them about politics,” Tumaris says. “I don’t really know their political views, and even if I do, I’m sometimes scared. What if this is a person the Chinese government sent as a spy? Or the Chinese government’s paying them to get some information from me?”

As one of the first Uyghurs to come to Philadelphia for college in recent years, Alim felt isolated. He hadn’t met many Uyghurs at his school, and he felt more distant than ever from the Han Chinese students with whom he shared his home country. Many of his professors, even those studying political science or history, had never heard of Uyghurs. It was a hassle to explain his identity, so he often told people he was from Turkey.

At home, conversations with his family were short—so many topics were off limits that their talks often trailed off into silence. His parents spent much of their calls praising the Chinese government in case of government eavesdropping. He had gone from having a large family and circle of friends in Ürümqi to knowing almost no one in the U.S. He struggled to connect with people in broken English, his third language.

“I don’t want to have that happen to other Uyghur students,” says Alim. After meeting his roommate, who is also Uyghur, Alim reached out to other Uyghur college students in Philadelphia through Facebook. After meeting Tumaris, Mirshat, and others, Alim began to host regular meetings at his apartment.

“I try to help provide that environment or atmosphere, make them feel they’re at home, or somebody cares about them. That’s a part of our culture, being Uyghur,” says Alim. “Those students, you don’t really know them back home. You don’t have any relation with them, but being Uyghur makes you connect.”

Students call it the Xinjiang House. When they visit, they leave America at the door. Inside, they speak freely in Uyghur. Alim cooks. His favorites are polo, spiced lamb pilaf, and laghman, hand–pulled noodles with stir fried meat and vegetables. He tries to keep the mood light; he thinks there’s more than enough to worry about outside the house. They talk about school, friends, and how things are going in Xinjiang. They cure their homesickness, at least temporarily, with food and stories.

Outside of gatherings, Alim checks in on the younger students, often in ways their own parents can’t. He calls often and gives advice on living in America. He lets the kids borrow his car to get groceries, and he takes them out for dinner and movies to celebrate the end of finals. During the beginning of the pandemic, he gave his extra masks to the other students.

“Even though we’re not blood–related, I really do feel like they’re my family here,” says Tumaris.

~

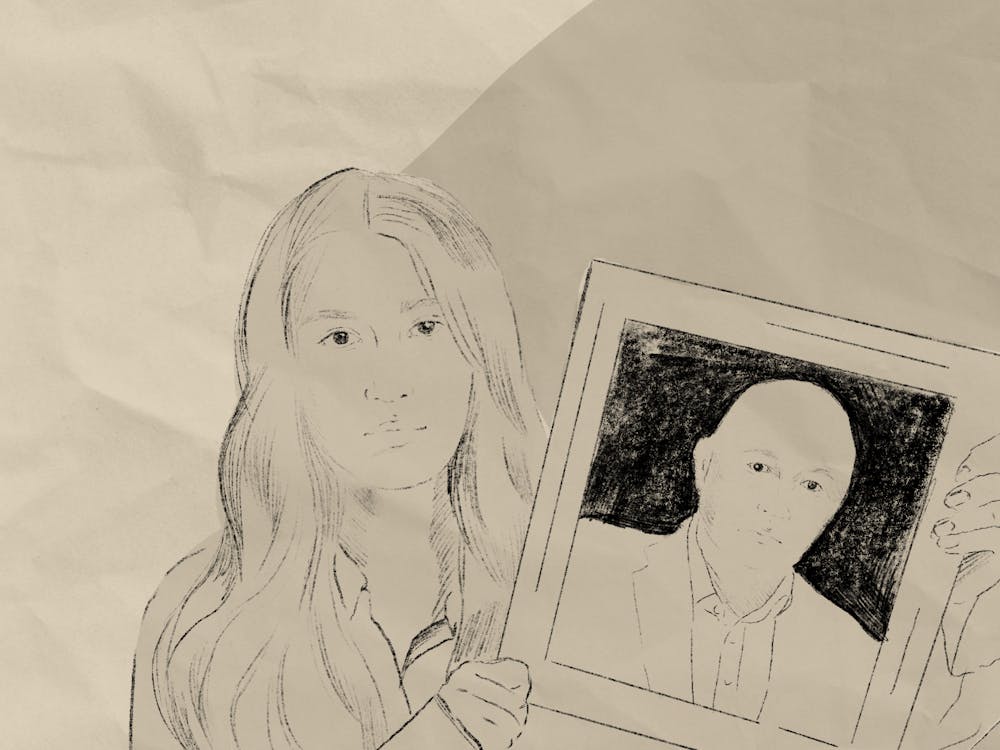

In 2016, Tumaris’ parents got clearance to visit her in the U.S. for the first time. Her mother landed safely in June, and the two drew up plans for a family road trip. Her father was supposed to come in September.

But the Chinese government had recently begun its crackdown on ethnic minorities in Xinjiang. Over the next few years, as many as 1.5 million Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities would be sent to concentration camps, and prominent Uyghur intellectuals would be targeted for “re–education” or arrested for promoting separatism.

Tumaris’ father, Yalkun Rozi, is a scholar and writer who compiled and edited Uyghur literature textbooks. Shortly before he was supposed to fly to the United States, Tumaris’ mother received a single message from him on WeChat: “I’m leaving.”

Tumaris hasn’t heard from him since. Her family found out weeks later that he was arrested for “inciting subversion of state power” through his textbooks. After being detained for years, Rozi was sentenced to 15 years in prison in 2018. To this day, Tumaris doesn’t know where her father is.

Tumaris was one of the first to experience what has become a shared trauma for Uyghurs living abroad. From 2016 to 2017, Mirshat watched helplessly as dozens of friends and family members unfriended him on WeChat. Word in Xinjiang had spread that people were being sent to camps en masse, and the government considered foreign contacts a sign that Uyghurs were communicating with terrorist organizations abroad. His parents sent only a vague message before unfriending him. He didn’t talk to them for two and a half years.

“We didn’t do anything wrong. We were just having normal conversations,” says Mirshat. “I was super careful about my language. I don’t mention anything political or anything sensitive. But now, because of this fear that the government imposed on our people, we can’t even do the most basic and normal things.” Mirshat learned later that during the period in which his parents cut contact, his uncle was taken to a concentration camp.

In 2017, Alim was in the middle of planning his wedding when his WeChat contacts dwindled from over 200 people to just seven. His father stopped showing up to family video chats without explanation. After weeks of uncertainty, his sister, who still lives in Xinjiang, told him that their dad had gone back to “school.”

“60 year–old seniors never go to university for study,” says Alim. He knew that his father had been sent to a camp, where he’d ultimately spend eight months before being released.

Five days before the wedding, Alim’s mother called him to say they could no longer keep in contact. He wanted to postpone the ceremony until he knew his father was safe, but she told him not to.

“You can do it without us,” she said. She placed her palm on her chest and drew her hand towards him.

“That means my heart will be with you. I will pray for you,” says Alim.

He got married at a mosque in Northeast Philadelphia on a cloudy August morning, dressed in a traditional black and gold wedding coat his parents had tailored for him years in advance. Twelve of his closest friends attended.

His father’s fate haunted the ceremony. Alim wouldn’t talk to his family again until early 2019. To this day, his family has not met his wife or seen his wedding pictures.

“I hated myself a lot. Instead of blaming the government, first I blame myself. It’s because of me,” he says. “If I had just studied in China, it wouldn’t have happened.”

Mirshat, Tumaris, and Alim might never return home. Evidence shows that China pressures Uyghurs living abroad to come back by threatening family members or declining to renew their passports. What happens to those who do is not clear, but it’s likely bleak. Because of her father’s position, Tumaris is certain she would be arrested or sent to a camp the moment she stepped on Chinese soil. Plans to move back to the city of her childhood are now a pipe dream.

“We came as students, but we stay here as refugees,” she says.

Uyghur students’ losses are felt as a collective. Every Uyghur knows someone in camps or prison. But from their anger, grief, and isolation grows an even greater determination to protect each other and their culture. The Uyghur community in Philadelphia has transformed into an activist network: the students keep each other updated on news in Xinjiang, attend protests against China’s policies, and send information on news outlets looking to interview Uyghurs. Tumaris, who was afraid for years to share her story, went public on social media to demand her father’s release from prison.

“There won’t be any benefits to staying silent,” she says. “Even if I stay silent, there’s a risk that bad things will always happen. It’s better if I speak up and let people know.”

Because of the danger to family and the mental toll of revealing their identities, not every Uyghur is able to engage in highly visible forms of activism, says Aydin Anwar, outreach manager for the Save Uighur Campaign.

“Activism can apply to anyone who really stands for the cause and is doing what they can from their ability to speak, write, pray. Those are all forms of activism,” she says. Up against a government trying to erase their religion and identity, simply cooking their food or sharing memories of home are forms of political resistance.

“Being Uyghur is all politics. You’re inside the politics,” says Alim. “If you have a chance [to share your story], I think every Uyghur has to do that—be the voice of people who are in the camps.”

~

Efforts to raise awareness have slowly begun to bear fruit. There’s been a rise in media coverage on the internment camps. More often than not, saying the word “Uyghur” in conversation causes a flash of recognition.

“I used to bottle up everything because I couldn’t trust anyone,” says Tumaris. “Now a lot of people are more aware of what’s happening to Uyghurs. I can be a little more open about what I’m going through.”

In 2019, restrictions appeared to ease slightly in Xinjiang. Both Mirshat and Alim were able to reestablish contact with their families. Alim and his parents started texting again on WeChat, mostly short messages, reassuring the other that things were still okay. After a month, they worked up the courage to video call. Alim saw his father’s face—much slimmer, gaunter—peering back at him on his phone screen.

They cried. There was much he wanted to ask about but couldn’t—the camps, his father’s health, whether the rest of the family was okay. Instead, they stared at each other in silence.

Tumaris still hasn’t heard from her father. Every month, she and her brother upload videos to Twitter, asking for information on his whereabouts.

All three students hope to return to Xinjiang, or if the situation continues to be unsafe, bring their families to the United States. But fighting for that right may take a lifetime.

“This is a very long journey,” Mirshat says. “It’s not going to be solved today or tomorrow. Maybe it will be solved in many decades, many centuries.”

So the students talk often about moving on—not forgetting what’s happened, but pushing through. They try to focus on the present. Lectures, protests, work shifts, and meals with friends leave little room for idleness.

But little reminders of home come in the shape of a building, a flicker of a memory, the feeling of the wind. Early summer mornings in Philadelphia—dewy and warm—make Tumaris think of the Xinjiang countryside, where her grandparents live. She tells me that One Liberty Place looks exactly like Zhong Tian Plaza, the tallest skyscraper in Northwest China. In her childhood, she was able to see it from her apartment window. Now, she likes to stand at Cira Green and look at One Liberty Place among the Philadelphia skyline. Here, she pretends she is somewhere that doesn’t exist yet—a Xinjiang where her father is free.

* Indicates a name has been changed for anonymity.