Since I was forcibly evacuated from London due to the coronavirus pandemic, I’ve used a VPN to keep my IP address firmly within the southern borough of Bermondsey, 4,854 miles from my current place of residence in Texas. Following Mubi United Kingdom’s ‘Focus On’ Retrospective in early May, I became fascinated with the streaming service’s spotlighted filmmaker Celine Sciamma, whose style—like that of many of her queer and feminist contemporaries—feels both palpably rebellious and earnest in its exploration of adolescent sexuality.

Recently, Sciamma has expanded the reach of her thematic interests, culminating in her 2019 César Award winning historical lesbian drama, Portrait of a Lady on Fire, which holds the male gaze as one of its central antagonists.

Despite the acclaim of Sciamma’s latest work, I find myself coming back to her first feature length film, 2007’s Water Lilies (Naissance des Pieuvres). Unlike many European auteurs, who predominantly avoid working with plots associated with Hollywood genres, she subverts the American teen movie paradigm, finding the radical potential of nascent desire.

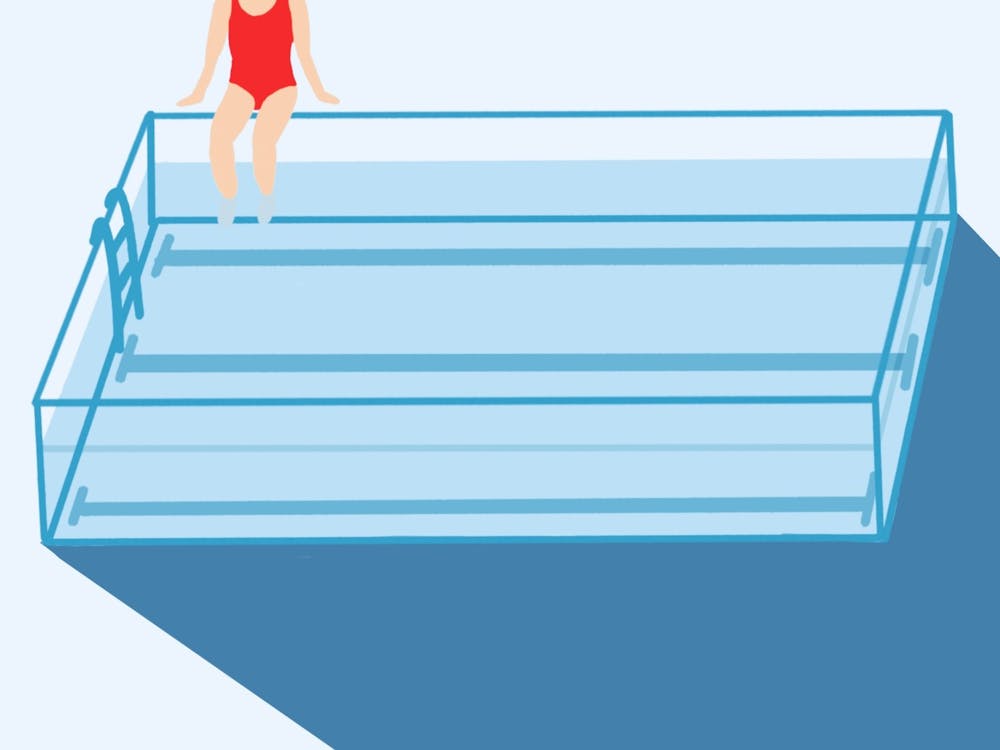

Returning to Cergy–Pontoise, the lower–middle class Parisian suburb where Sciamma spent her childhood, Water Lilies’ plot centers around three 15–year–old teenage girls, each involved in their local synchronized swim team. Marie, the protagonist whose boyish figure precludes her from successfully socializing with her male peers, becomes infatuated with the female team captain, Floriane, attending every practice to watch her skillful movements underwater.

Unlike the other girls of their suburb, Floriane revels in her burgeoning sexuality, taunting her prudish peers with a rumor that she has already had sex many times with many different men. Alienated from others, Floriane builds an amorous, tense bond with Marie, dragging her along on her many dates.

The film’s third outcast, Anne, fails to live up to conventional beauty standards, which ultimately keeps her in a space of arrested development. Though Anne desires to become a sexual actor like Floriane, she is perennially seen as a child by those around her, gorging on Happy Meals and bashfully giving her crush presents in the boy’s locker room.

Sciamma explained that she wanted her actors to fit the "American Pie template. The beautiful girl had to be very beautiful and blond, and the fat one quite uninhibited and awkward."

When I watched Water Lilies, I cringed in front of my laptop screen, reminded of the exciting, grotesque moments that guide us all towards adulthood. For Sciamma, embodied responses from spectators force us to not voyeuristically watch her characters’ lives, in a Hitchcockian manner. Instead, we become active participants in their journeys.

Her teenage characters in this film do not necessarily ascribe to any particular sexual identity but merely deviate from traditional understandings of girliness and womanhood. As a proponent of an oppositional lesbian gaze, she reminds us that filmic ambivalence, in both content and form, challenges heteronormative ways of seeing those around us.

In one of the movie’s most tender moments, Marie and Floriane find themselves in a Parisian night club, with Floriane aiming to sleep with an older man, an ostensibly impartial actor who will rip her virginity off like a bandaid. The girls sweatily dance directly in front of one another, making the viewer believe that their same–sex impulses will culminate in a kiss.

However, Sciamma’s lesbian gaze does not offer a simplistic understanding of desire, one that myopically suggests that sexual acts indicate one’s preferences. In this sense, the audience do not need a kiss to know the way Marie and Floriane feel about one another.

In the following sequence, Floriane rashly embraces a man in his stuffy, petite–bourgeoisie car, with Marie only footsteps away. Unable to bear witness to such profound insincerity, Marie rushes to the man’s window, exclaiming: “My friend needs to hurry up, her daddy’s waiting for her. He was worried about perverts picking us up.”

Sprinting back to the comforts of their Parisian suburb, barely escaping the cynicism of adulthood, the two girls cling to one another on the side of the highway, panting and laughing as they catch their breaths. Brushing off the danger of her encounter, Floriane assertively spits on the concrete road and tells her friend that he was an awful kisser anyway.

For me, Sciamma offers a deeply empathic and liberating gaze—one that is not simply restricted to the limited space of the movie theater or streaming site. Hilariously, I’m reminded of each freshman orientation week I had to witness as an older student. While I live as a recluse at Penn, safely tucked away on the border between West Philadelphia and University City, I thought of the faint sounds of first years laughing and screaming blocks away from me, enjoying a very odd moment in their entry into adulthood.

If Water Lilies is a melancholic celebration of the entry of three 15–year–old girls into their teenage years, then perhaps convocation is the definitive arrival of first–year students to maturity.

Celine Sciamma’s Water Lilies is available for streaming here.