Justin Horn (C ‘20) was standing in the back of the room at Joe Biden's campaign headquarters in Philadelphia, suspense gripping him, as he watched the Vice President’s team receive some race–altering news. Philadelphia’s long winter was melting away on the early spring night, the office packed shoulder to shoulder with enthusiastic Biden staffers, eyes glued to the news. Beto O’Rourke just endorsed Joe Biden, as did Mayor Pete Buttigieg and Senator Amy Klobuchar, shortly after dropping out of the race for President. The once twenty–eight candidate Democratic primary field was narrowing down to just one, and Justin was watching it happen in real-time.

The 2016 Presidential election shook Justin to his core. Soon after Donald J. Trump’s victory over former First Lady Hillary Clinton, Justin became a political science major. He hoped to stop a disturbing trend he saw developing in American politics, one that gave a platform to dangerous white nationalism while ignoring the real needs of the American people. For Justin, landing a fellowship with the Biden campaign last fall meant taking one big step towards achieving this goal.

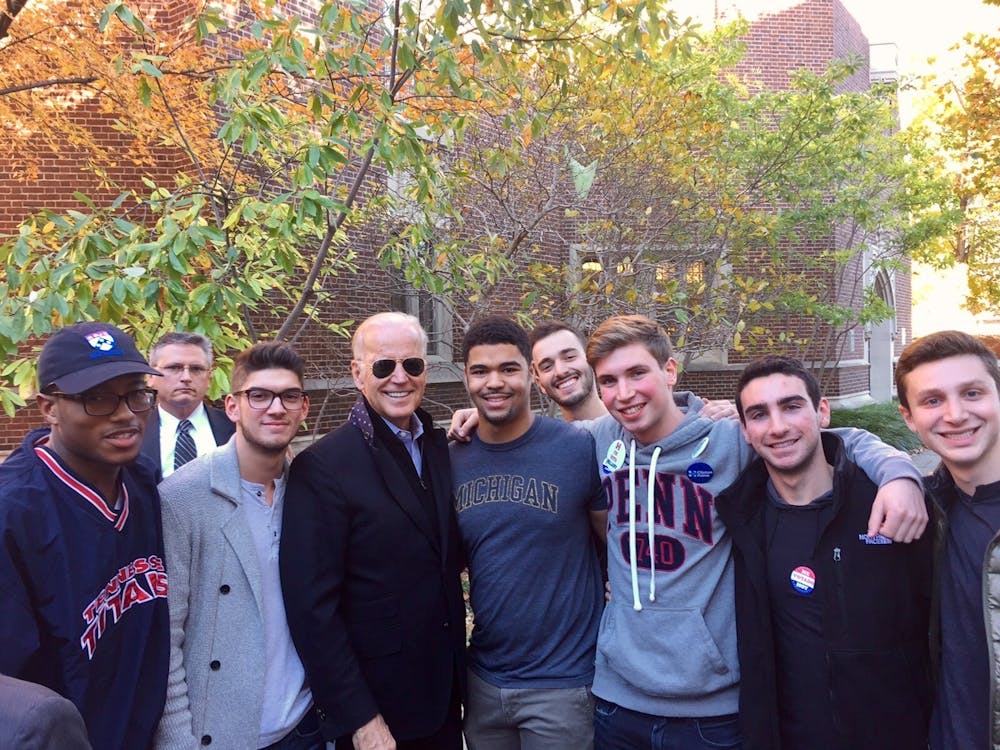

Courtesy of Justin Horn

In recent weeks, many students who previously viewed politics as largely peripheral in their lives woke up to issues of race, class, and governmental leadership. The rising political tide seems to be lifting many young people out of their electoral slumber, a good sign for organizers like Justin who want to see Donald Trump ousted from office in November. As the coronavirus rages on, calls for systemic change grow louder, and election day appears closer on the horizon, the political impact of young people will be more important than ever. Many Penn students are becoming involved in politics in this unprecedented current moment. For others, however, political engagement has been a cornerstone of their young–adult lives. Here are two Penn students on what it's actually like to work on a campaign during one of the most contentious years in American politics.

Courtesy of Justin Horn

Justin started his work for the Biden campaign as a part–time fellow answering emails in September of 2019. The Vice President gets thousands of emails, with issues ranging from healthcare to gun control to criminal justice reform. Justin’s job as a correspondence fellow centered around creating personal responses that let constituents know that the campaign was listening to their specific concerns. Justin found himself reading heartfelt letters from Americans both excited—and deeply concerned—about the future of their country.

After his fellowship ended in December, he continued to do other kinds of volunteer work as the primary field grew smaller and more contentious. Biden’s Philadelphia headquarters asked Justin to lead a volunteer trip up to New Hampshire to canvass in advance of the February 11 Democratic primary. Dragging his boots through the falling snow, Justin walked the dimly lit back roads and the quaint downtown strip of Claremont, New Hampshire. The dead–of–winter New England wind nipped at his cheeks as he knocked on doors in the small city, hoping to convince New Hampshire Democrats that his candidate would be the best to beat Donald Trump in November and bring about comprehensive change.

Justin acknowledges that his ardent support of Biden from the outset of the race was unusual as a college–aged Democrat. Many young people were inspired by leftist candidates such as Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, who advocated for Medicare for All, cancelling student debt, and instituting free college. For Justin, however, his support of Biden’s moderate candidacy came down to his ability to beat Trump as a tenured and emotionally plugged–in candidate.

“I had full faith in the idea that after such an un–empathetic President, we needed empathy in the White House,” he says. “That would be the best way to steer America back on track and back toward the ideals that we all aspire to."

On that cold night of February 11 in New Hampshire, however, Bernie Sanders was declared the winner, followed closely by Pete Buttigieg, then Amy Klobuchar, and Elizabeth Warren. Joe Biden was fifth, with a slim 8.4 percent of the vote.

In Justin’s words, “It was a disappointing result.”

But, he didn’t give up hope, returning to the Philadelphia office to make phone calls to Democrats across the United States. There were 48 primaries left, and it was anyone’s game. Eighteen days after New Hampshire, Joe Biden swept the South Carolina primary with nearly 50 percent of the vote, indefinitely changing his place in the race. Biden’s campaign picked up speed from South Carolina, and Justin has been along for the ride ever since.

Now, from his home in Los Angeles, California, Justin is stepping into a new role as a field organizer. With Joe Biden as the presumptive Democratic nominee, Justin’s focus has shifted towards the general election. With the coronavirus pandemic continuing to ravage the United States, however, his work will look different than any election cycle of the past.

“I loved going to the Philadelphia headquarters of the Biden office. There was a really good energy there. So I definitely miss that, and it's not the same doing the work from my room,” Justin says.

Most of his work will be conducted remotely as he makes phone calls, responds to constituent email, and helps train other volunteers in advance of election day. Although the campaign will be different than any before it, he feels that the pandemic has brought to light many problems Americans were not paying attention to before.

“The Coronavirus woke a lot of people up, and I can see that in the emails,” he says, “A lot of people weren't paying as much attention to politics because their 401k or their wallet was okay. But I think this pandemic has really made people see that we don't have national leadership at all. This crisis has made it painfully obvious and people are starting to realize that it really matters who's President.”

Justin also notes that calls for racial justice have raised the election’s stakes even more.

“When you look at issues of race and who's going to bring this country together rather than divide it, a vote for Joe Biden is a vote for that.”

This March, Adelaide Lyall (C ‘24) found herself back in her home state of Maine after her gap year travel plans were cut short due to the coronavirus. Since the beginning of the nationwide lockdown, she’s served as an intern for Sara Gideon’s campaign. Gideon, the current Speaker of the Maine House of Representatives, recently clinched the Democratic nomination for Senator on July 14, going on to challenge Senator Susan Collins in November. Collins, the state’s incumbent Republican Senator, is the target of much criticism after siding with the G.O.P. multiple times despite positioning herself as a moderate, swing voter.

Courtesy of Adelaide Lyall

Adelaide is currently a field organizer for Southern Maine, a traditionally blue area with a large population relative to the rest of the state. Due to the pandemic, much of her work, like Justin’s, is now virtual. Adelaide organizes phone banking, rallies student groups, and communicates with older people in the area via phone calls and emails. In advance of Maine’s primary, her main goal was to build up turnout and make sure voters know how to request absentee ballots.

Aside from the technological difficulties of campaigning in the age of COVID, Adelaide reflects on what it’s like to pour all of her time and energy into a Senate primary election.

“I watched the Kavanaugh vote and I fought really hard to make sure that Susan Collins didn't repeal the Affordable Care Act,” Adelaide says.

Adelaide talks about how her love for her home state and her close following of politics made this election incredibly important to her. Many Mainers, however, have not followed Susan Collins this closely, and this race will not be met with Adelaide’s same passion.

“I care so much about this race” she says, adding, “It's hard to convince [people] to feel the same way about it as you do. Something that's challenging about any sort of political work or activism is recognizing that you have to meet people where they are.”

One surprising high of her election work is her conversations with everyday Mainers, cooped up at home and anxious about what the future holds.

“People are so isolated in their homes and Maine has a really old population,” she says, “People are really willing to talk on the phone right now and want to hear what you have to say. They’ll connect with you on a more personal level on the phone because they just really want to talk to somebody.”

In trying to get Sara Gideon elected, this side effect of the coronavirus may just help Adelaide’s team advance towards victory. Like Justin, she feels that the stakes of elections across the country are much higher than ever.

“People are really struggling right now,” she says with a sigh, “Therefore they care about the decisions that elected officials are making in a different way.”

As the election cycle continues on through November, Penn students will send absentee ballots near and far, and many will line up at Houston Hall on November 3rd to cast their final votes and get their red, white, and blue sticker. For Penn students like Justin and Adelaide, however, the fight is only beginning, and they’ll be there to see it all the way through.