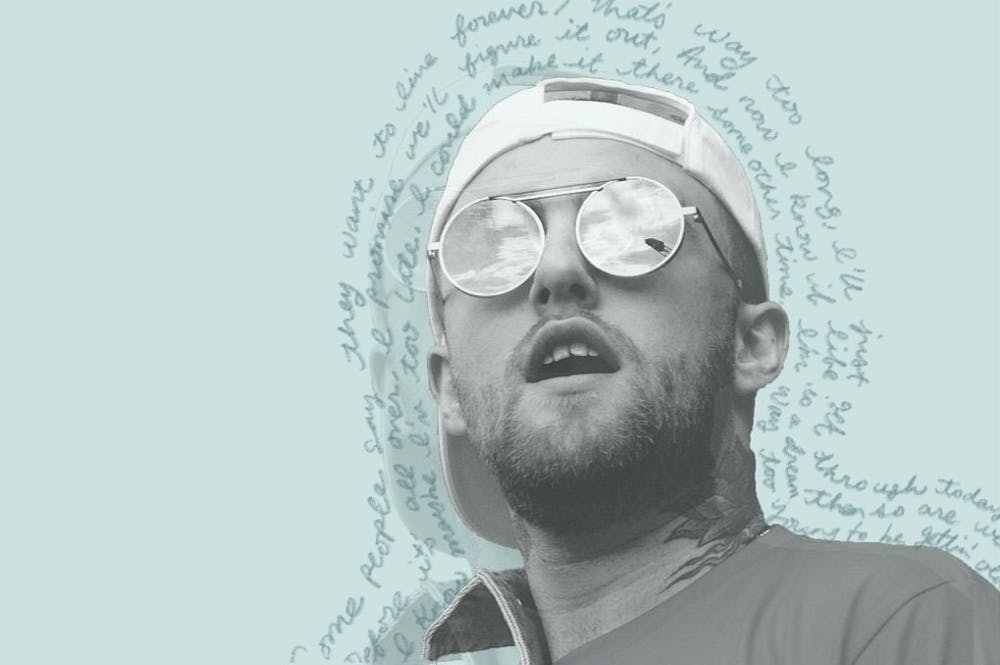

On Aug. 3, 2018, Mac Miller released Swimming, intended to be the first of two companion albums. On Sept. 7, 2018, Miller was found dead in his home, in what was later determined to be an accidental overdose of fentanyl, cocaine, and alcohol. On Jan. 17, 2020, Warner Records posthumously released Circles, the intended companion to Swimming, and the final studio album by Malcolm James McCormick.

How does one talk about Circles? To do a straightforward review is impossible, as albums do not spring fully formed from an artist’s head, but are rather built, piece–by–piece, from their experiences. At the same time, to reduce the album to the final tragedy of Miller’s short life and untimely death would be an insult to the artist, who wanted to be remembered for his music, not his personal life's turbulence.

The easy answer: begin with the music. Most hip hop traditionally bears sparse instrumentation, allowing the rhythm and rhyme of the lyricist to take center stage, but Circles makes particular use of Miller’s vocals, gruff and raspy and tired. Songs like the title track, “Good News,” and “That’s On Me” use subtle instrumentation to ground Miller’s rhymes, but keep it purposely sparse and light. One of the final tracks, “Hands,” showcases the most instrumental features. Collaborator and producer Jon Brion, who completed the album, said in the liner notes that Miller wanted the song to be “big and expansive and cinematic … He was really excited but had no idea how one would even go about that.”

Brion was given, in many ways, a thankless job. He had begun working with Miller before the singer’s death, providing suggestions on how to bring a vocal track to life. As such, he was tasked with completing the album, adding percussion, strings, overdubs, and other flourishes, put together with conversations between himself and Miller. Brion’s influence on the album is subtle, as it should be—this is Miller’s album, and his job is not to create it, but to present it, and Brion does so without pageantry. This is Mac Miller, unfiltered and genuine.

The decision to release an album after an artist’s death is always a difficult one. Those left behind must ask themselves whether this is what the artist in question would have wanted, or if any posthumous recordings are just a cheap cash grab. Amy Winehouse’s producer Salaam Remi said to NME in 2011, in response to the release of Lioness, that “it makes no sense for these songs to be sitting on a hard drive withering away,” and that it would not lead to “a Tupac situation,” referencing the seven posthumous albums by rapper Tupac Shakur.

Often, posthumous releases are compilations, a series of songs left behind with no plan, no track listing or cohesive album, simply snippets recorded and pushed away for another time. Circles, on the other hand, is a coherent product, backed by a clear vision. In this way, it resembles less Lioness and more Come Over When You’re Sober, Pt. 2, released a year after Lil Peep’s accidental overdose. Peep’s mother saved his recordings from his old MacBook, and producer Smokeasac completed the album.

Death due to overdose, as was the case with Miller, Winehouse, Peep, and so many others, is sudden and unpredictable. David Bowie was able to release Blackstar as a “parting gift” to his fans, knowing the liver cancer that eventually took his life would not be immediate, which allowed him the time to plan his final releases. Miller had no such luxury.

At the same time, his final recording is haunting in the ways in which it seems to predict his death. Many of the lyrics reference his desire to fix his health and relationships while there’s still time. On “Good News,” he says, “I know maybe I'm too late, I could make it there some other time,” and on "Surf," he insists, “Before it's all over, I promise we'll figure it out,” while “That’s On Me” suggests an acute awareness of his problems—as well as a genuine desire to improve them.

Other tracks feature more abstract mediations on life, death, and reality. On “I Can See,” Miller says, “And now I know if life is but a dream then so are we / Show me something, show me something, something I can see.” Meanwhile, on “Complicated,” he says, “Some people say they want to live forever / That's way too long, I'll just get through today,” before insisting that “I’m way too young to be gettin’ old.” The one cover on Circles, of Arthur Lee’s “Everybody,” is particularly haunting with its chorus of “Everybody's gotta live / And everybody's gonna die.”

Swimming and Circles were meant to be companion albums, but Miller had plans beyond those two. Brion told The New York Times that “There were supposed to be three albums: the first, Swimming, was sort of the hybridization of going between hip–hop and song form. The second, which he’d already decided would be called Circles, would be song–based. And I believe the third one would have been just a pure hip–hop record.” In saying this, Circles’ place becomes more ambiguous. On the one hand, it represents closure, acting as the other half of the album that preceded it. On the other, an awareness remains that there was supposed to be more.

At some point, a musician releases their final album. Sometimes this is due to a purposeful retirement, or a prolonged illness that allows them to plan their final words. Other times, as with Miller, the artist’s life and voice are cut short. Miller, even after his death, seems to implore his fans to take comfort in what he did leave behind, and not what could have been. As he tells the listener on “Blue World,” “Fuck the bullshit, I'm here to make it all better / With a little music for you / I don't do enough for you.”