Perhaps you’ve heard that Benjamin Franklin was a womanizer. Articles like this one—"Was Benjamin Franklin a Pig?"—reflect the extent to which this rumor has gained traction in the public consciousness. Despite his accomplishments as a father of the nation and founder of Penn, Franklin’s memory is often tainted with the label of a reckless philanderer.

Carla Mulford is a professor in the English department at Penn State. She visited the Library Company of Philadelphia this past week to give a talk, titled “Franklin & Women,” in which she dealt with these rumors—their origins, their validity, and her own opinion on the subject. While she mostly focuses on literature of politics and economics, she has spent close to 30 years studying Franklin and his work.

The event began with a brief reception in which academics, library frequenters, and curious community members—average age of 60—gathered to chat over charcuterie boards and beer in one of the library’s historic foyers. Gradually, close to a hundred people shuffled into the larger room where the lecture was to take place, and the chatter of excited intellectuals died down in anticipation.

Soon after she began her talk, Mulford made her dissenting position clear: Franklin’s view of women was actually quite progressive. She attributed his unfavorable image mostly to his political unpopularity at the time, and drew upon the other ways Franklin demonstrated his views on women—namely by using female aliases as his mouthpieces for social commentary.

Franklin was detested by many for his reform ideas in a 1764 election, and pamphlets just so happened to surface at the time, calling him a “lecher” and a “womanizer.” To be sure, Mulford didn’t outright deny the allegations that Franklin was into philandering—there is consensus in the historical community that he did enjoy the company of women—but she argued that this was not an exhaustive treatment of his relationship with the sex entirely.

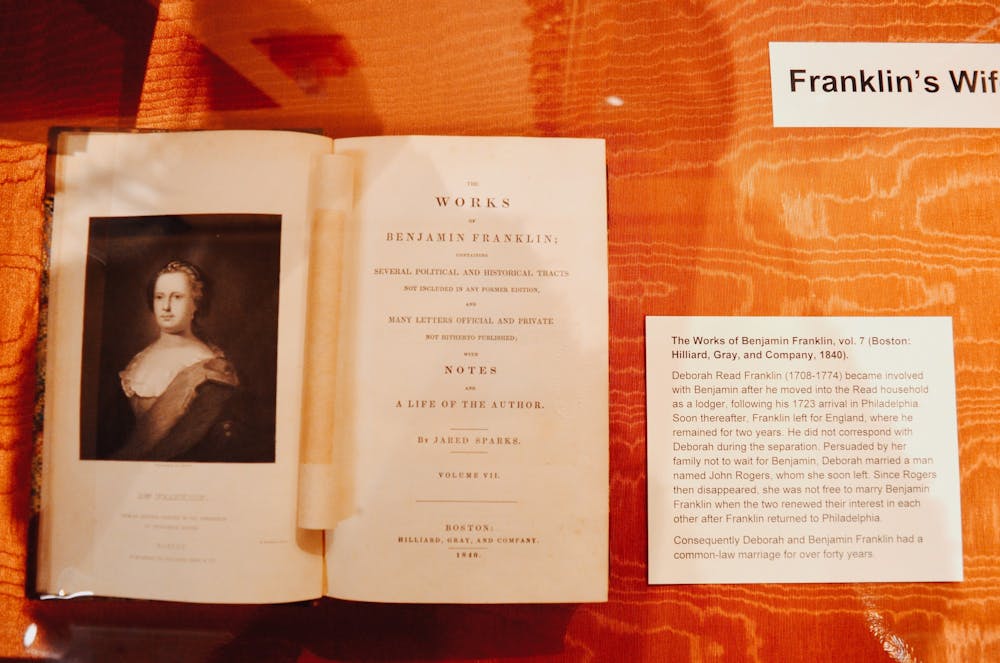

He considered women equally talented to men, as well as gifted homemakers and business-minded in their own right. Not only this, but he also felt that men were prone to hot–headedness at times, and women more to stability. Additionally, we know through his writing under the pseudonyms Silence Dogood, Celia Single, and Polly Baker that Franklin felt there was a “conservative double standard” in how women were treated as opposed to men. They were unreasonably expected to err more on the side of modesty and virtue. Mulford implied that these thoughts, despite seeming backward by modern day standards were progressive given the time. She concluded the talk with a discussion of how Franklin’s wife, daughter, and sister were all self-starters, with experience handling family finances, business, kitchen work, local politics, and clothes making.

Mulford did not unfairly subject Franklin to modern standards of social understanding. Instead, she looked at how his philosophy fit into the already flawed society in which he lived. So yes, maybe he was a “pig” by our modern standards. Or maybe he was just a good person existing in a society that favored men by default.