On Nov. 6, 2019, riot grrrl band Bikini Kill announced a 2020 tour that includes a series of shows across the United States and Canada. Less than a week after the tour was announced, eight shows had sold out and several more dates were added to make room for the demand. This will be the first Bikini Kill tour in over 20 years, and in the time that they were gone, the band became the face and heart of the riot grrrl movement.

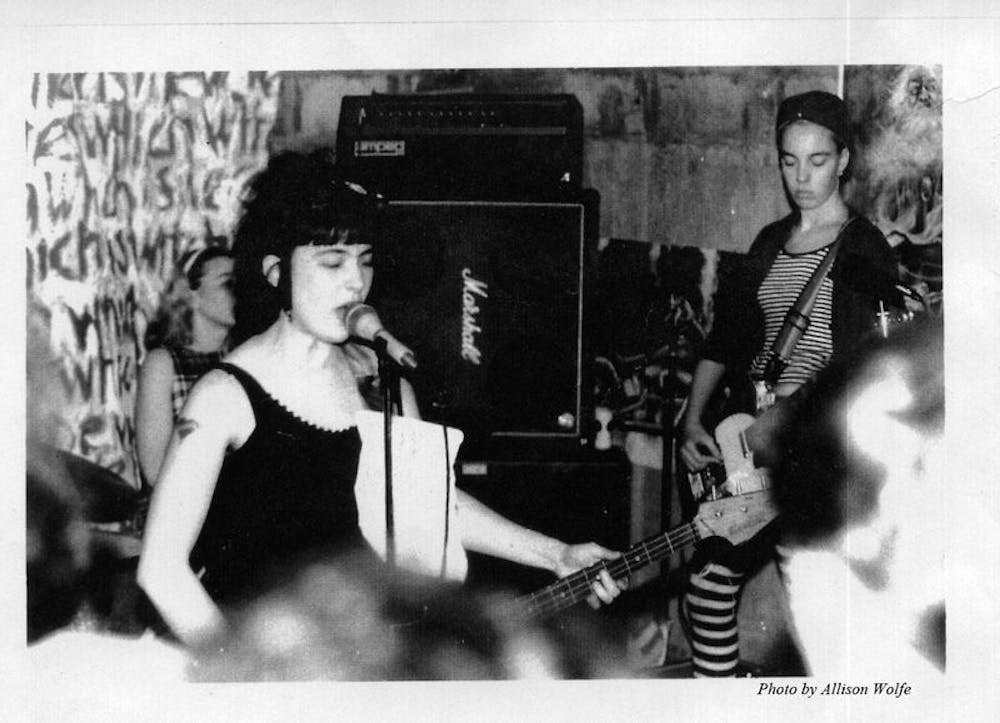

Bikini Kill began in Olympia, Washington in 1990, when frontwoman Kathleen Hanna, bassist Kathi Wilcox, and drummer Tobi Vail met while attending Evergreen State University. Billy Karren, the only male member of the band, joined soon after on guitar. The band was known for being unapologetically female, from the anti–sexism lyrics to Hanna demanding “girls to the front” in the pits of live shows. Naturally, such a loud voice inspired backlash: “Guys would come to yell really horrible stuff, call me all kinds of names, sometimes be physically violent,” Hanna told The Guardian in 2014.

Ian MacKaye, of Minor Threat and Fugazi fame, produced the Bikini Kill EP on the independent record label Kill Rock Stars, and Hanna struck up friendships with other punk and grunge icons. The Nirvana song “Smells Like Teen Spirit” was named after a note that Hanna scribbled on Kurt Cobain’s bedroom wall, and she makes a cameo in “Letterbomb” on Green Day’s seminal American Idiot. Yet, for all of its underground attention, the members of Bikini Kill never reached the same levels of fame as their male peers.

In 1998, Rolling Stone reported that the band had officially broken up. Kill Rock Stars spokeswoman Maggie Vail told JAMtv that the group had disbanded about a month before the news broke. “It’s been seven years, and I think they just decided it was time to move on,” she said. “Bikini Kill wasn’t that active, but their presence was really influential in the music world.” Such an announcement might have meant the death of the scene, but Olympia–based bands like Sleater–Kinney and a newly–reformed Bratmobile were happy to continue the riot grrrl mantle.

The three female band members kept busy, with Wilcox and Vail forming Frumpies and Hanna fronting both the electronic rock band Le Tigre and the East Coast alt–rock band The Julie Ruin, the latter of which included Wilcox. Although various band members would team up for each other’s new projects, there was no Bikini Kill reunion until a surprise performance at Pitchfork editor Jenn Pelly’s book release in 2017, when Vail, Wilcox, and Hanna performed “For Tammy Rae.”

This Pitchfork event was presumed to be a one–time reunion, until the band announced a handful of shows in New York and Los Angeles at the start of 2019. All female founding members would participate, and Karren was replaced with Erica Dawn Lyle, who met Vail when they performed together in a short–lived band called Knife in the Eye. When asked to consider playing with Bikini Kill, Lyle told Pitchfork, “I felt like I was getting drafted or something.”

Shortly after these 2019 performances, it was announced that Bikini Kill would headline the third night of Chicago’s Riot Fest, a three–day punk and music festival. During her set, Hanna paused to tell the audience, “I just wanted to say that we’re a feminist band and we’re headlining a festival,” calling attention to the mostly masculine lineup: The Friday and Saturday headliners at Riot Fest 2019 were blink-182 and Slayer. Vail announced during the performance that it had been over twenty years since the band played in Chicago, with their last tour stop being the Fireside Bowl in 1995.

The upcoming North American tour will be the largest set of performances that Bikini Kill has played since the '90s. Many of the venues they play will be larger than the band is used to: When they pass through Philly in May, it will be at Franklin Music Hall (which has a capacity of 2500), not an underground or basement venue. Since they first broke up, the band went from having a cult fanbase to acting as the face of a major musical movement.

In 2015, Hanna told Portland Mercury that she wasn’t interested in a riot grrrl revival. Her advice to young punks wishing they had been part of her scene was to “look at what punk rock feminism brought to the table and find the stuff that you can take into the future that's great, and throw the stuff that was stupid away.” Vail, meanwhile, told Pitchfork that she doesn’t see the reunion as a “nostalgic exercise,” but that “it’s a way to keep these songs alive.”

Regardless, this Bikini Kill reunion is part of a larger riot grrrl renaissance. Sleater–Kinney is in the midst of a national tour, queercore band Team Dresch released their first new song in almost 20 years this past summer, and new bands like Pussy Riot and The Regrettes have all sprung up in the past decade. The genre originated in response to the male domination of the hardcore scene, but it soon became a tool to decry misogyny worldwide. The modern resurgence is indicative of the current political climate. “These same issues still exist,” Vail told The Guardian. “Being a woman in public is very intense, whether it’s in the public eye or just walking down the street at night by yourself.”

Hanna, Vail, and the rest of Bikini Kill have little interest in being the leaders of the scene. They want, like most musicians, to play music that’s important to them. The works they write and perform are deeply personal and uncensored. That enough people related to these songs to turn Bikini Kill into national icons, whether in the '90s or today, speaks to the power of the band and the revolution they created.