To say the political climate at the inception of the travelling art exhibition 30 Americans was different from that of today would be an understatement. When the Rubell family first premiered the exhibition of contemporary art by African American artists in 2008, reviews of that first show glimmered with the shiny hope of an Obama presidency. In today’s context, the show holds simmering undertones of protest.

30 Americans is a travelling exhibition that began its journey at the Rubell Family Collection in Miami in 2008. Since its debut, the exhibition has made appearances in Raleigh, Washington D.C., Milwaukee, New Orleans, Detroit, and Cincinnati, among other places. Now, at the Barnes Foundation of Philadelphia, 30 Americans returns to the northeastern United States for the first time since 2011, when it made a stop at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. Including over 60 works of video, sculpture, painting, photography, and drawing, 30 Americans brings fresh perspectives of American identity to the Barnes.

Exhibitions like 30 Americans can be puzzling to the white art establishment. Previous reviews of the show have questioned “why, aside from the color of their skin, any of these artists belong in a room together,” or criticized it as being “an exhibition tailored to leftist sentiments”—a remark overheard from a fellow patron. But by imposing these political limits on the exhibition, critics often fail to understand the way each piece explores a facet of American identity that many museums have yet to include in their own permanent collections.

Some of the most remarkable pieces in the Barnes’ version of 30 Americans are three of Nick Cave’s famous Soundsuits, full body costumes meant to be worn, that Cave created as a response to racial profiling by police. Notably, these Soundsuits cover the entire body, suggesting that Cave sees covering his body as the only way to avoid this profiling.

These Soundsuits are in communication with several of the other pieces in the exhibition, even those radically different from them in medium and presentation. One of Glenn Ligon’s famous oil stick works, Stranger #21, hangs on a wall nearby. Stranger #21 takes its inspiration from a James Baldwin story entitled “Stranger in the Village,” which navigates Baldwin’s experience in an all–white Swiss town in the 1950s.

Known for his play with text, Ligon makes quotes from Baldwin’s story completely illegible in this piece, by covering the canvas with coal dust. This material is both dark and sparkling in a way that reminds viewers that coal, under pressure, becomes a diamond. In tandem with Baldwin’s words, Ligon comments on his own identity by meeting the story of overwhelming whiteness with a black surface that tempts prolonged examination into what’s hidden beneath it.

Every piece in 30 Americans brings up complex questions of American identity, sexuality and violence, power and status. The exhibition’s curator and Associate Professor of History of Art, Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, said that “wherever it has traveled, 30 Americans has changed things, in the art world and in the community,” at a press preview for the show. And in an essay Shaw wrote for the exhibition’s latest catalogue, she elaborates on this, naming its impacts on the Detroit Institute of Art and the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh, where the permanent collections have since evolved to represent more African American art.

Shaw said she can’t wait to see “the phenomenal impact this exhibition will have.” President of the Barnes Foundation Thom Collins added that “30 Americans resonates with the Barnes’ mission and history,” as Dr. Albert C. Barnes once established a scholarship for young Black artists. But while 30 Americans is undoubtedly tied in some ways to the Barnes’ history, this exhibition also finds ways of challenging it.

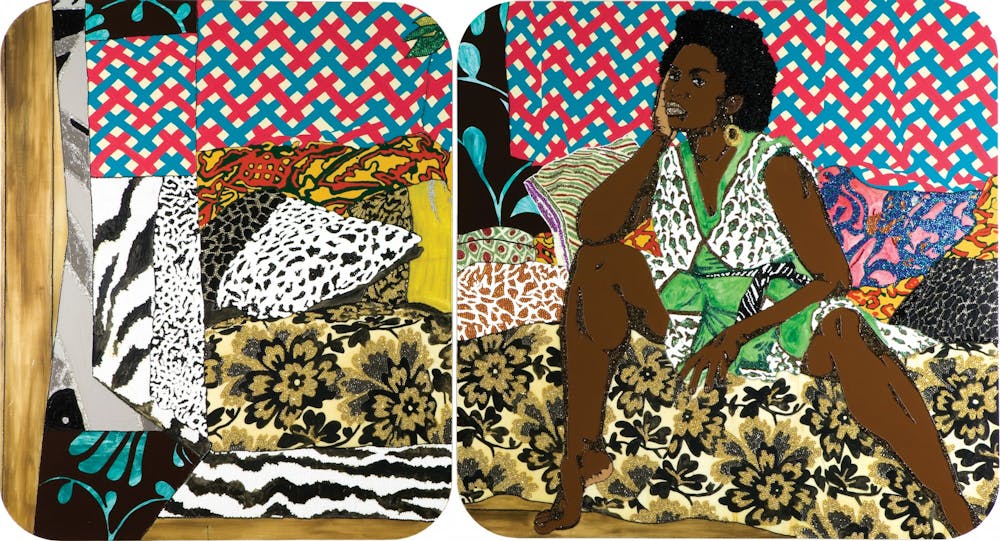

With works by renowned, record–breaking artists like Jean–Michel Basquiat, Kerry James Marshall, Lorna Simpson, David Hammons, and Kara Walker, 30 Americans pushes against the limitations of the identity purported by the predominantly white collection of the Barnes. Yes, these artists are all Black, but to leave their commonality at that would be a misunderstanding of the power of this exhibition.

As Shaw remarks in her catalogue essay, 30 Americans is an exhibition that is not only important for what it tells us, but for what it can inspire. She recounts the story of a photo of a young girl admiring Michelle Obama’s portrait by Amy Sherald, closing with a quote from Shinique Smith, whose mixed–media piece Crone–Huntress stands tall in a room of the exhibition that also includes works by Xaviera Simmons, Lorna Simpson, and Mickalene Thomas.

In regards to when the exhibition made its stop in Washington D.C. in 2011, Smith remarked, “I just realized that when young people like me come to the museum to see the show, there will be kids like me...seeing Lorna Simpson and Carrie Mae Weems, and thinking ‘I could be in this museum.’”

30 Americans is a show that is shocking and sad and loving, each piece shining in its confrontation with traditional notions of American identity in the art world. But today especially, these confrontations gleam with a resolve and inspiration that may be more pronounced than it was at its debut. In part inspired by the progress of the first Black presidency, this exhibition now stands in a much darker social context under the looming shadow of rampant white supremacy. Now, more than ever, this vision of a culturally diverse future seems harder and harder to picture. But 30 Americans is here to remind us of its possibility.