There’s one story that Reverend Chaz Howard never gets tired of telling. Thirty years ago, when Howard was in middle school, he remembers playing basketball at an all–boys Jewish sports camp in Maine. “It was the best of times and the smelliest of times,” he says with a laugh.

In one game against a rival camp—“I had the same animosity towards them as I do toward Princeton”—he recalls feeling so in–the–zone in the game until the referee called four “ticky–tack, cheap, phantom fouls” on him. The coach wanted him to keep playing, but Howard took himself out of the game “in full NBA prima donna fashion.” After a few minutes of sulking, the coach came over to Howard in an effort to motivate him to play again, saying, “Chaz, we need you out there. I know it’s unfair, I see that, but we need you out there.”

Howard likes to tell this story because he knows how unfair life is sometimes. Especially today, in the presence of so much rampant racism, sexism, homophobia, anti–Semitism, Islamophobia, and other iterations of hate, the temptation to leave, to “move to Canada, to Africa, to wherever else” is strong.

“I think about this story often, because I think so many of us feel defeated,” he adds, sitting in his Houston Hall office. “One of the most common things I hear from people in this room is ‘I just wanna give up,’ but we literally need you out there.”

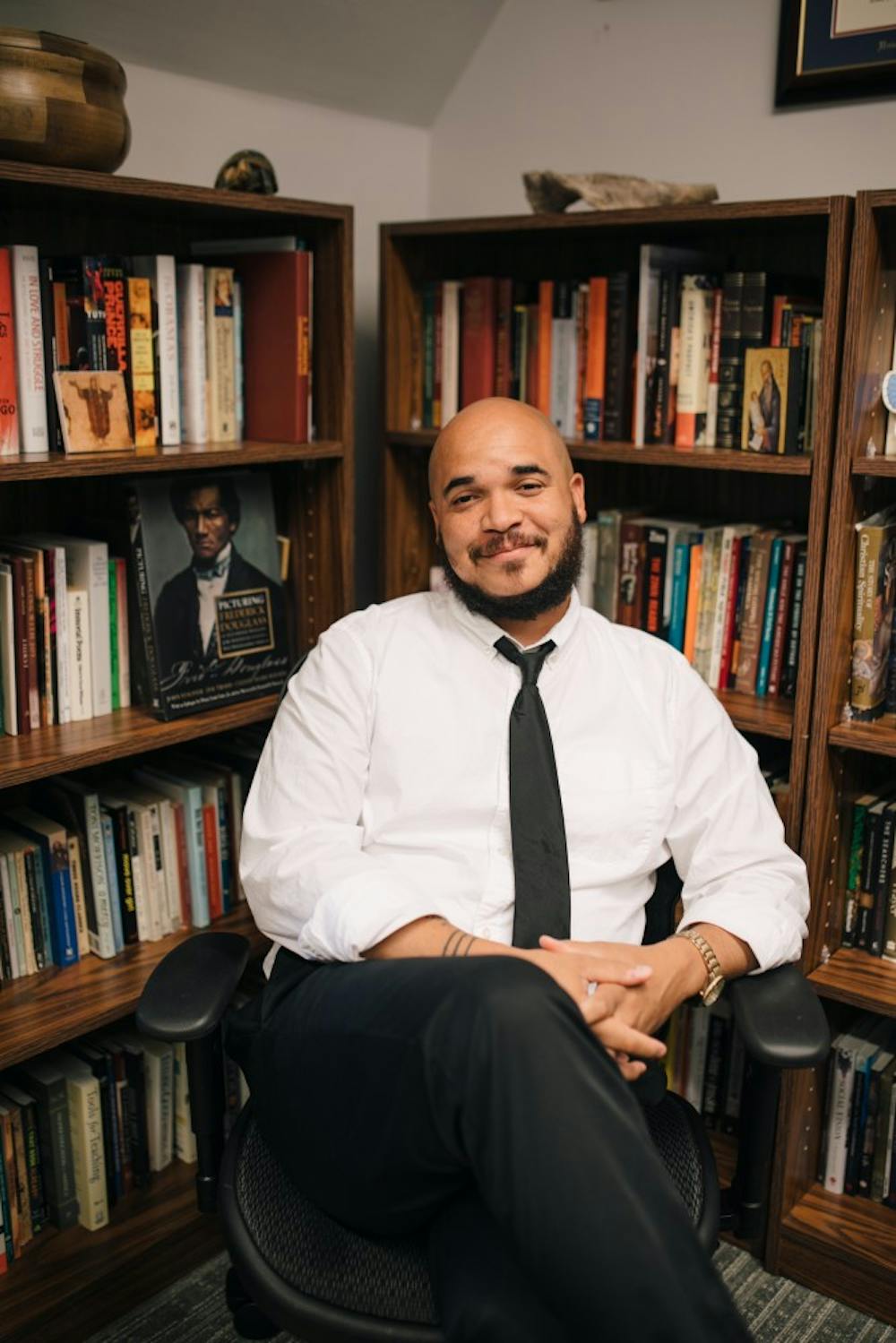

As Penn’s University Chaplain, Howard acts as a leader for the diverse religious life at Penn, helping to oversee student activities and official ceremonies. He graduated from the College of Arts and Sciences in 2000, and began his chaplaincy here in 2008. At that time, his office was “essentially in a closet in the Quad”—a stark contrast from the spacious room in where he now resides, comforted by dark leather armchairs, an antique chess set, and his blue betta fish, Will Ferrell.

He often thinks about the way, “religion at Penn has changed over time. We were once a militantly secular school, and now we see ourselves as a nonsectarian school with a vibrant religious and spiritual life that’s part of our celebrated diversity,” Howard remarks.

Though much of his role as chaplain involves overseeing the religious groups that comprise this vibrancy on campus and participating in official university ceremonies like Convocation, he also meets with many students individually for the purpose of mentorship or as part of a counseling journey in conjunction with other on–campus resources like Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS). Conversations that begin with Howard acting as a friendly sounding board can evolve into ones of loneliness or troubles at home, for which his office’s amiability provides a haven.

That’s how Angelica Du (E ‘20) knows him these days. “My boyfriend used to work in the Chaplain’s Office, so I would do homework there every afternoon, and since Chaz worked there, we would have conversations from time to time,” she says.

Though she got to know Howard in these moments throughout her first two years at Penn, Angelica’s connections to him grew stronger after she joined the Christian Union in her junior year and started attending events where Howard spoke about race and racial reconciliation in the church.

“This past year, I was struggling a lot with mental health, and he reached out to me saying ‘Hey, do you want to start meeting with me regularly, so that I can help you through what’s going on?’” Angelica felt grateful for his offer, at first almost rejecting it because she didn’t think these meetings were a part of his job. “Actually, it’s a big part of my job, to meet with students,” Howard says.

But job is a tricky word for Howard. He often thinks about the difference between his profession and his vocation—or between what he wants to do and what he sees himself as called to do. He understands his calling as helping the homeless, and has spent a long time working with Project HOME, a local nonprofit organization that seeks to combat the cycle of homelessness in Philadelphia.

“I think the 25–year–old me who was doing street outreach through Project HOME was in a very different season of life than 47–year–old me, who physically just can’t stay up to do a night shift on the Parkway anymore,” he says.

Howard now uses his platform to teach, write, and speak about the pandemic of homelessness. He’s working on a new book on the topic that’s slated to come out next fall.

His passion for combatting homelessness is rooted in specific memories of seeing homelessness at Penn as well as ongoing education about the homelessness crisis. “I remember walking to class when I was an undergrad and walking under the bridge near 1920 Commons, and seeing someone sleeping on the heat grate there,” Howard says with a look of raw emotion. “That was probably the first time that I was really heartbroken here at Penn.”

Howard now tries to incorporate principles from his earlier work into his job now. “It’s maybe a stretch, but a Catholic author Henri Nouwen talked about how college students are the most homeless population out there,” he says.

Howard wants to be careful not to diminish the real homelessness of those forced to sleep on benches or struggle in the cold, “but the emotional vulnerability of life on the street mirrors emotional vulnerability of people who are in college. The feeling of not being seen, feelings of being isolated and alone—I see that on campus sometimes, on every campus.”

The responsibilities of Howard’s job often mean that he has to help handle intense—and sometimes grave—emotional situations on campus. In the midst of a death or emergency at Penn, his voice is often the one that relatives will hear first as the bearer of bad news. And it takes a significant emotional toll.

“I think that’s far and away the most difficult thing to do,” Howard says, “to find out from Public Safety that someone’s died, and then we’ll call that person’s parents to tell them the thing that they feared the most in life has happened, and then to hear their parents scream and drop the phone.”

He delivers these words slowly. The memory of the recent death of Gregory Eells, the former executive director of CAPS, is fresh in his mind.

“Greg’s loss a few weeks back really, really hurt for several reasons.” With tragedies like this one, Howard believes there’s a temptation for Penn students to look for flaws in the administration’s handling of the news. “This sounds patronizing, and I don’t mean for it to, but there’s a base distrust of ‘the man’ that young people have, and should have—that I had, and still have a little bit.” He sees this distrust as the source of people’s anger with the way the administration sometimes handles times of suffering.

He wants students to know that administrators and Penn employees care about mental health, even if students don’t always see it. “There are 50 to 60 thousand employees here, and a lot of us care,” Howard says. “A lot of us speak openly about our own vulnerability.”

This compassion extends beyond moments of tragedy. Though Howard espouses a communal increase in joy, peace, justice, and love, he knows that preaching those ideals is easier than adopting them. One case that’s gained national attention is that of Amy Wax, a Penn Law professor notorious for her controversial comments regarding race and immigration. Calls for Wax’s termination have led to little action, due to the protection of her tenure status.

“I think as we engage just vitriolic, hateful, wrong stuff like Professor Wax’s comments that are literally white supremacist and are hateful—it’s easy to be hateful toward her too. And I think that’s dangerous,” says Howard. While he also wishes Wax weren’t employed at Penn after her comments, he still wants to respect her as a human.

Howard saw the same tension between love and hate exemplified in a social justice protest he participated in outside of the White House last summer with Penn’s former chaplain and current Associate Vice Provost for Equity and Access, Reverend William Gipson, and some other local clergy.

One thing led to another and “we got arrested,” says Howard. “But there was a Mexican–American priest or pastor right next to me, and as he was getting turned around to get cuffed, right in front of the White House, he turned to it and literally made the sign of the cross as a blessing, and started praying for President Trump and his marriage and his kids,” he recounts. “And he did it in Spanish.”

Howard takes this moment as an example of how to “fight with one hand and embrace with the other.” He sees this conflict as one of the ultimate challenges to humanity—one that’s “so much easier said than done.”

He applies this same attitude when thinking of how to react to the recent mass shootings at places of worship like those at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, and the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, to name only a few. Howard acknowledges the terror that comes from these attacks, saying that “the great mark of our age right now is fear.”

As chaplain, he helps students, particularly those of affected religious communities, through these difficult times. Tafshena Khan (N ‘20), president of the Muslim Students Association, says that Howard played a big role in comforting Penn’s Muslim community after the New Zealand mosque attacks in Christchurch. “We had to organize a vigil overnight,” she says, “and he really played a key role in helping us do that, and making sure that there was a safe space for us on campus.”

But beyond wrestling with these darker questions, Howard still sees glimmers of hope in these tragedies in the way they shed light on the balance between despair and prayer. The testimonies of faith that he saw in those religious communities that returned to services the following week after such chaotic violence were examples of grace and courage to Howard.

“Fear,” he says, “is the garden of sin.” He likes to use an image of a candle in a dark room to help explain the way that he understands the relationship between fear and love in the world. “When you bring a candle to the room, you help to push back the darkness there. I think there’s a similar way we can dispel fear from society when we respond with love.”

Beyond giving talks and support for the different facets of religious life on campus, part of Howard’s job also involves teaching. Alongside one of Penn’s associate chaplains, Steve Kocher, Howard helps lead a Graduate School of Education class and program called iBelieve, or formally, Interfaith Dialogue in Action. The program brings together students of diverse faith backgrounds, even atheism, with a mission to foster dialogue and a commitment to service among them.

The class, which is open to both undergraduate and graduate students, includes trips “that we hope build on the dancing story Chaz loves to tell,” says Kocher, in reference to a TEDxPenn talk Howard gave about an interfaith service trip to New Orleans that ended with a group of Orthodox Jewish students and deeply observant Muslim students dancing together in a jazz club.

The goal of these classes and trips is not only to strengthen the connections between different religious communities on campus, but also part of a larger effort by the Chaplain’s Office to “make any student feel welcome,” says Kocher. They try to make sure that the office does a good job of connecting to non–religious support networks as well.

Yasmina Ghadban (E ‘20), a member of Penn’s Reach–A–Peer Helpline (RAP–Line) who helps train new volunteers, says that of all the staff and faculty members that come to give advice on counseling, “Chaz and his lessons are by far the most memorable.” Though Howard’s advice for new RAP–Line members mostly involves advice on how to engage with someone in issues of faith, Yasmina says “he also shares his own story, and shares ways we could do better in having a more faithful community at Penn.”

Howard hopes to improve upon this role of being both mentor and friend to everyone in the Penn community as he moves forward in his chaplaincy. “In the first several years of one’s career, one’s kind of climbing. I feel like I’ve stopped climbing,” he says, reflecting on his last eleven years as Penn’s youngest chaplain ever. “I’m interested now in really trying to solidify the foundation of religious life on campus and repair some of the holes that might be there.”

Until he fully sorts out where his next callings will lead him, Howard will continue to write and teach and pray and lead, using love as his guiding principle. He often speaks of a need for God in his work, “some sort of supernatural, divine underpinning,” that he prays to in the most difficult moments.

He calls out to say, “I need you. I cannot do this on my own.”