In chaos theory, the ‘butterfly effect’ is the phenomena which supposes that the slightest shift in initial conditions can surmount to substantial changes in final circumstances. If you are anything like me, then the simple sight of y = mx + b induces an uncomfortable back–of–the–throat queasiness. I know for a fact (read: Wikipedia skim) that Jennifer Egan majored in English Literature (C'85), yet, her novel A Visit from the Goon Squad parallels a physicist's investigation, as it tracks initiality, or the unpredictability and impulsivity of human nature, to finality, which she calls “A→B.”

To the bludgeoning beat of naked emotion that thrilled 90’s rock, the form of Egan’s novel is as much of a complex character as the ones who reside within her plot. Through the use of split timelines, a range of narrative voices, and even Powerpoint, she captures around forty years through 13 different points of view. This range provides 13 different narrations, immersion in split–second decisions, and the shredding effects following loss of others and self—all propelled by the goon of time.

Currently, Egan is the Artist-in-Residence for the UPenn English Department. Previously, the department has welcomed artists to instruct creative writing classes. But, Egan's role is different: she is teaching "English 086: Self, Image, Community: Studies in Modern Fiction," seamlessly instructing attentiveness to close-readings, contextualizing works within history, while indulging her students with bites of her own approach to writing.

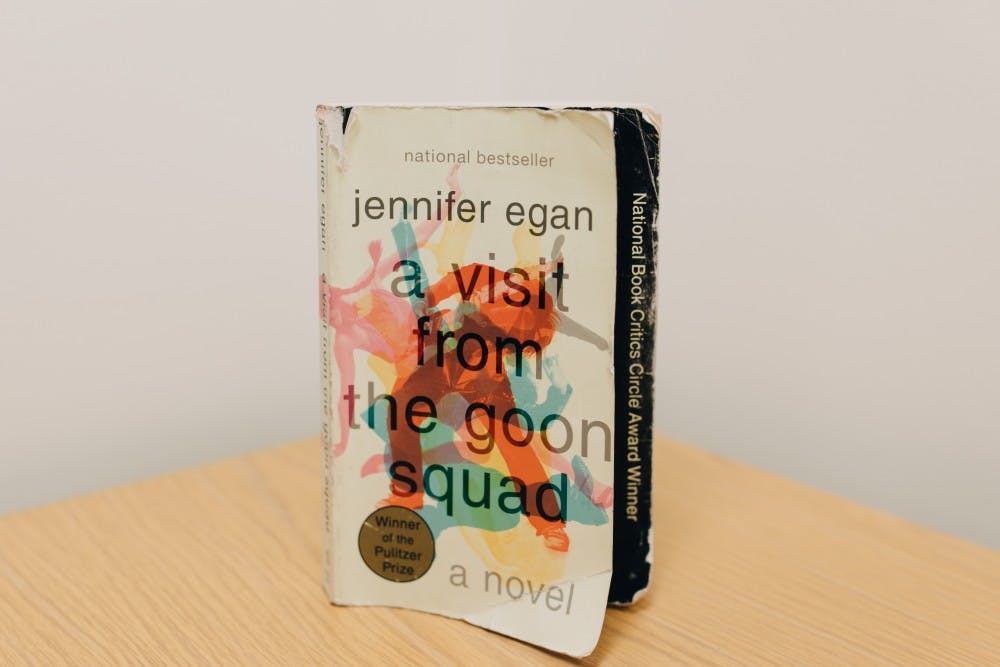

As a writer, Egan has authored several novels. In 2017, she published Manhattan Beach, a New York Times bestseller, and recipient of the 2018 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction. In 2010, she published — and according to my overwhelmed bookshelf, this is saying a lot — my favorite novel, A Visit From the Goon Squad. Not only did the novel win my heart, but also the 2011 Pulitzer Prize, the National brook Critics Circle Award, as well as the Los Angeles Times book prize.

The third chapter, "Ask Me if I Care," displays Egan's attentiveness to the double entendre of minor choices. The first meaning is in terms of age, the rash decisions committed in teenage simplicity, before time ages our notions of right and wrong. The freckle–loathing Rhea describes the inception of her best friend’s, Jocelyn, relationship with the hedonist, coked–out Lou. It is Rhea who observes their relationship through the blitz of a thousand eyes at their three person dinner and under Lou's arm as he demands oral sex from Jocelyn. Yet, Jocelyn is not the epicenter of the chapter, it is Rhea, swelling with tears and existential questioning of what causes infatuation and what degree of caring, or not–caring, makes a person real.

It is only until twenty years have lapsed (or, one chapter, for the reader) that we are provided with Jocelyn’s narration. In "You (Plural)," Egan features the second meaning of minor choices. It is resides in the literal, the actions that we fully expect to be inconsequential, and are far too often proven incorrect. Situated in Lou’s once–riotous–now–sterile home, Jocelyn is forced into a state of reliving the time that has passed since her teenage hitchhiking and running away with Lou to returning to live with her mother, who ticks off each day she’s been sober. The reader experiences the excruciating personal and dark results of Jocelyn’s teenage years, and it is one of Egan’s many insights into the wreckage resulting from our seemingly futile decisions.

The novel’s centerpiece of loss’ ripping impacts become even more pronounced in "Out of Body." Rob is a NYU undergraduate whose college career began with his arm around Sasha as her fake boyfriend. All at the arm's length of a second person narrative, exhibiting Rob’s distance from himself, the “one who is saying” and from his friends, “who is doing whatever it is,” this chapter delves into the effects of suicide throughout the novel. At first, it is the discomfort that Rob feels amongst his friends, prompting his litany of apologies that ends with “I am sorry I make you nervous because I tried to kill myself.” Then, it is the finality of the chapter, where Rob drowns after swimming in the New York River.

The "Out of Body" chapter shows Sasha as a focused student, who abstains from the drug usage her friends and boyfriend engage in, attempting to leave behind her Italian life of theft and (me— postulating) prostitution. However, in the first chapter "Found Objects" Sasha is years old and has relapsed into shoplifting, and in her apartment is a picture of Rob. The final chapter shows that Sasha is married to Drew, her college boyfriend and one of Rob's best friends. These bookends portray the instrumentality of the end of Rob’s life and the effects it espouses on the characters throughout the novel.

Egan leaves the reader on a note that is simultaneously and paradoxically somber yet hopeful. The constant acceleration of time has situated the reader in New York in 20[XX] — Egan purposefully withholding the transfixed date from us (I'm not sure if it was in attempts to relieve or heighten our anxiety, but, for me, definitely the latter). Her futuristic New York vision portrays the pervasive loom of surveillance, marketing paradigms aimed at child consumerism, and the ability to "T” each other when several minutes of conversation has rendered us too exhausted to continue. Yet, this lack of connection hallmarked by technology is subtly juxtaposed to the connection which has undergirded the novel, such as between characters Bennie and Sasha, Sasha and Alex, and Bennie and Alex.

It is almost as if, after authoring an entire novel that’s theme was dedicated to the ways time shifts and distorts memory, Egan asked the reader, “Remember Alex?” And, if you do not, well, case–in–point. Alex, the once–twenty–something who went on a date with the yes–no smiling Sasha, is working as a “parrot” for Bennie Salazar, her past boss. The layers of this connection draws Egan’s novel full circle. All of the fluctuations through time—Alex’s date, Bennie firing Sasha, Sasha leaving New York—are accelerated in four condensed words, “she had sticky fingers,” and an intentional stroll towards Sasha’s old apartment, to discover she is no longer there.

Sometimes, time can be summarized briefly. Other times, it is a goon hurdling us through constant twists and turns. Yet, Bennie’s conciseness cannot slow the series of connections and changes and pauses as time persistently ticks on, but rather lays the groundwork for more journeys from A → B, to complete “some history together that hasn’t happened yet.”