It’s been said that if you were to meet an exact copy of yourself, you wouldn’t recognize the copy as being you. That’s partly because we can only see our own image in reverse. Whether it be in mirrors or in pre–flipped selfie cameras, the us we recognize isn’t us at all. Instead, the version of ourselves with which we are most familiar is our opposite, our exact converse staring back at us. And this version is the only self that we know.

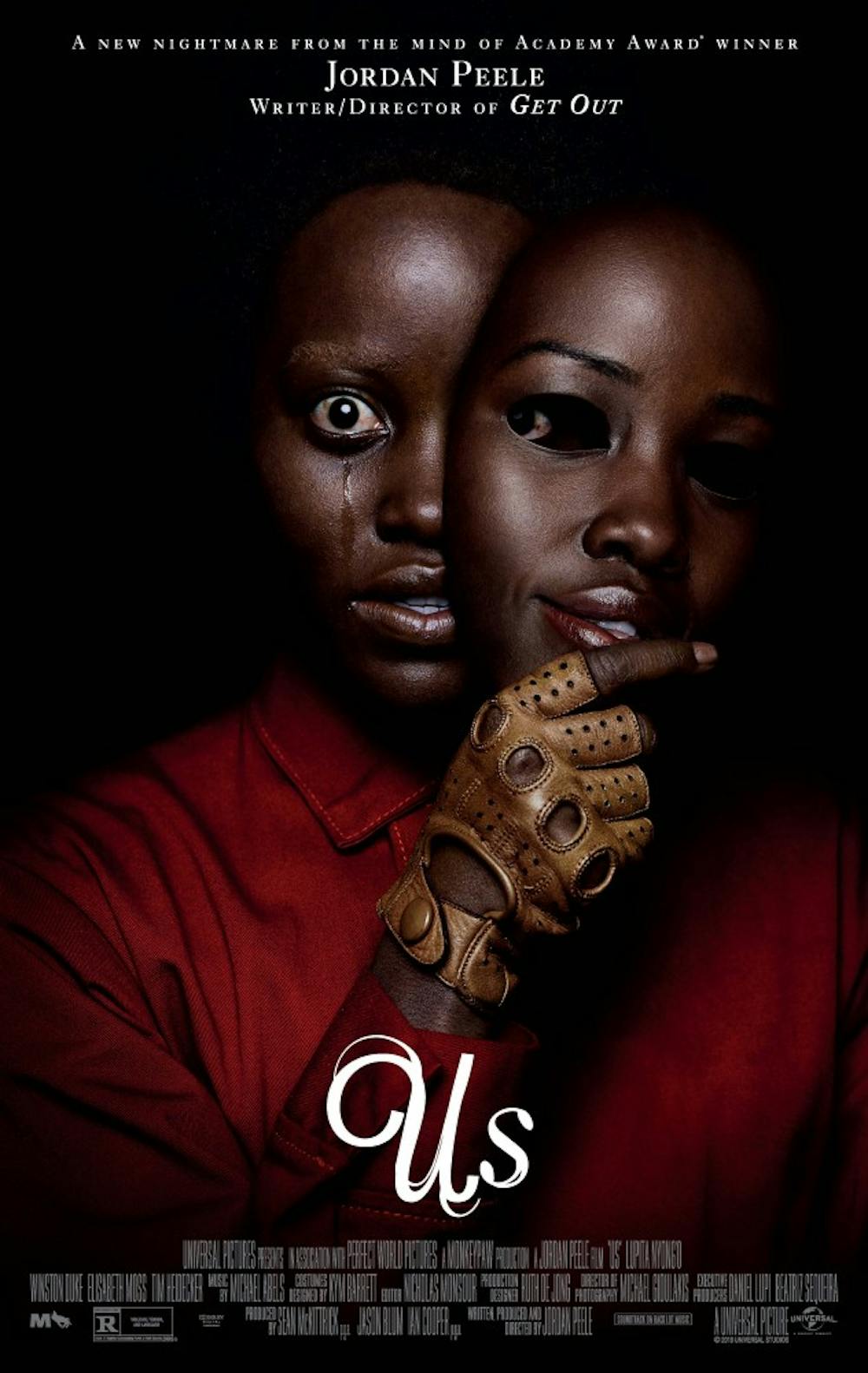

This idea of the warped self is one of the central themes of Us, the sophomore effort of writer/director Jordan Peele. Even the plot of Us is a sort of mirrored image, where the past and present are similar, yet eerily different. The film begins in 1986, with our protagonist, Adelaide, on a family vacation with her sparring parents. Adelaide wanders off into “Shaman Vision Quest” a funhouse with a caricatured and vaguely offensive Native American figure overhead, inviting onlookers to come in, to find themselves. Years later, Adelaide (Lupita Nyong’o) returns to Santa Cruz with her own family. Gone is the scared little girl who disappeared into that cartoonish hall of mirrors, which, incidentally, has now been renamed “Merlin’s Enchanted Forest”. The funhouse where Adelaide got lost on that fateful night is exactly the same, just glossed over, given a new, more politically correct sheen to counteract its insensitive past.

SPOILERS AHEAD!

Adelaide has been running from what happened in the funhouse all those years ago, and try as she might to gloss over it, she simply cannot move on. She knows her past is catching up with her. She can feel it. It turns out that all these years, she has, quite literally, been running from her own shadow— her own tethered doppelgänger named “Red.” Every member of Adelaide’s family has their own, slightly more evil mirror image, who have arrived tonight to finally exact their revenge. It turns out that everyone in the U.S. has one of these doppelgängers. Originally created as part of a government experiment, these people were forced to live a life underground, acting only as a shadow tethered to their above ground counterparts. For every happiness anyone feels, their shadow feels pain. The message here is clear: everything in our country is built on the backs of those who never get to experience it for themselves. Us isn’t just about evil or horror, its about the pervasive culture of greed and privilege and class in America. Our doppelgängers (or the "Tethered") are invisible, yet we are tied to them, whether we know it or not.

Perhaps the most telling line of Peele’s allegory comes in the beginning of the film, soon after Red arrives. When asked who they are, Red strains the following reply: “We’re Americans.” This underscores the message of Us and one of Peele’s most biting criticisms of America to date— we are the haves and the have–nots, the seen and the invisible, the “us” and the mirrored selves we refer to as “them.” The theme of warped mirrors is everywhere in Us, even beyond the funhouse: with every cracked mirror and repeated movement, with every forced imitation the Tethered perform, we are reminded that they are simply mirrors of those we are used to seeing.

And with all the references to duality and the past, it’s hard not to think about Peele’s own career. Us is Peele’s second feature, and while it is something entirely its own, it's also inextricably linked to 2017’s Get Out. Universal acclaim is a rare phenomenon in Hollywood, and earning said acclaim with a horror movie is even rarer. So when Jordan Peele’s genre–bending directorial debut Get Out was released in 2017, the film was heralded as revolutionary.

Importantly, Us is not Get Out. But one must imagine that the success of Get Out was still fresh in Peele’s mind. How does one follow up an unsuspecting masterpiece? There’s something distinctly overeager about Us, as though it's an attempt to eclipse the long shadow cast by its predecessor. Just as Adelaide attempts to outrun her shadow, Peele is attempting to make something bigger and better than his first film.

It often feels like Us is answering all the wrong questions. Those it answers explicitly (like the two monologues by Lupita Nyong'o included for backstory) are completely unnecessary, while critical information about how exactly the world Peele has constructed works at all is never even touched upon. So, while Get Out doesn't require a huge suspension of the reality of reason, Us does; which is probably why it feels like such a departure from Peele’s previous work and like more of the same simultaneously.

Still, Us is a resounding accomplishment all on its own. One has to applaud Peele for taking on such an aggressively involved concept for his sophomore effort. Peele manages to touch on so many different parts of American identity while focusing on only one family: he captures us and the U.S. in Us.