In 1968, Penn students protesting the war in Vietnam staged rallies outside the on–campus recruiting sessions of Dow Chemical Company, which supplied napalm to the Department of Defense. The demonstrations forced Dow to cancel recruitment events at Penn two years in a row. Anti–war activism only escalated—between February and March 1969, there had already been a six–day College Hall sit–in, a faculty research strike, and numerous student protests against the university’s involvement in biological and chemical warfare research.

On March 4, 1969, students and faculty organized a teach–in dubbed the “Day of Conscience.” Classes were cancelled across Penn—at the suggestion of the Provost—and over 1,200 students attended the teach–in to hear about “the use and misuse of scientific knowledge” and “the role of the university in society.” It is the legacy of this event that the Faculty Senate invoked for “Teach–in 2018,” held this March.

Teach–in 2018 repurposed the language of the Day of Conscience, stating that it would examine “the University’s role in society” and the “use and misuse of scientific knowledge.” In 1969, the phrases referred to a critical analysis of Penn’s involvement in chemical and biological warfare research and its impact on surrounding low–income neighborhoods. In 2018, they entailed expert panels on artificial intelligence, lectures on positive psychology, and an “augmented reality scavenger hunt.”

The official Teach–in 2018 website announces that it is “Penn’s first teach–in since March 1969.” But a trawl through The Daily Pennsylvanian archives reveals a long tradition of teach–ins at Penn, starting before 1969 and continuing through every decade since. Penn students used the teach–in to discuss topics ranging from the Gulf War to the War on Drugs. Many were critical of the university and explicitly anti–administration, focusing on issues like racism at Penn, tuition and rent increases, graduate student unionization, and gentrification.

As recent as 2011, a group of Penn students and faculty organized a teach–in called “What the Fuck, Penn?” It took place at the Compass on Locust Walk and covered issues including Penn’s role in gentrification, its treatment of dining workers, and hiring processes for faculty of color.

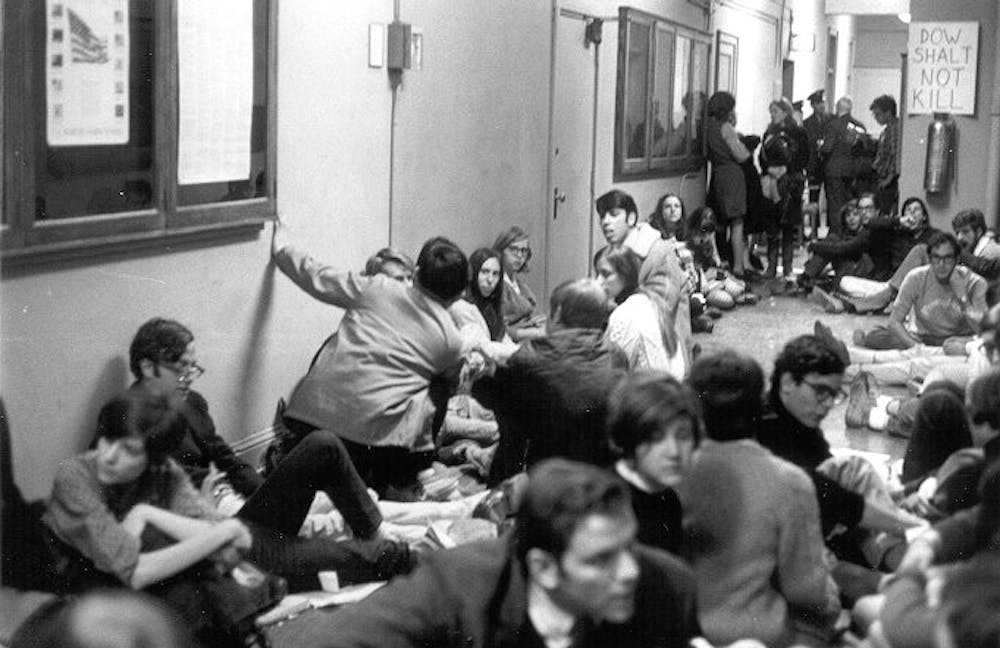

Student protest, sit-in held in Claudia Cohen Hall | University Archives and Records Center

“It was the teach–in at the compass, and we were questioning Penn’s moral compass,” says Social Welfare PhD candidate Meghna Chandra (C ‘13, SWP ‘22), who co–organized the teach–in. In the promotional video for the event, Penn professor Walter Palmer narrates, “As students, we must ask the impertinent question: whose bones and blood are we walking on for our privilege?”

In May 1990, around 100 students, faculty, and staff braved the rain to attend a teach–in on College Green protesting President Ronald Reagan’s appearance as keynote speaker for the University’s 250th anniversary celebration. 19 people—students and professors—spoke over three hours, highlighting the Reagan administration’s damaging policies towards higher education, the AIDS crisis, and women’s rights, which they said made him an inappropriate figure to invite to Penn.

But the teach–in wasn’t just aimed at Penn students. Sociology professor Fred Block told The Daily Pennsylvanian at the time that he was speaking at the teach–in because “the University administration has forgotten the consequences of Reagan’s policies.” Professor emeritus Edward Herman, playing on Keats, declared: “The modern university says, ‘Money is power. Power is money. That is all ye know on earth and all ye need to know.’”

Neither of these teach–ins were mentioned in the promotional material for Teach–in 2018. John Noakes (GR ‘93), who co–organized the 1990 Reagan teach–in as a graduate student, isn’t too bothered by the lack of official acknowledgement. “I won’t take personal offense,” he laughs. “I think it’s a much bigger act of cooptation to take the term ‘teach–in’ for something that’s sponsored by the administration than it is to ignore ones that happened in between.”

Teach–in 2018 was the brainchild of the Faculty Senate. Engineering professor Santosh Venkatesh, Senate Chair during the teach–in and one of its principal architects, says he and other members felt a sense of urgency around issues like “fake news,” rising authoritarianism around the world, and “an increased disquiet and distrust in the body politic.”

Venkatesh says the organizing process for Teach–in 2018 was “driven top–down,” from the Faculty Senate. Teach–ins like the one against Reagan, though, were organized by Penn students and sympathetic faculty members, often to protest administrative actions, or as part of larger student activist movements, like the 1986 teach–in organized by the Penn Anti–Apartheid Coalition, which campaigned for Penn to divest from companies with ties to South Africa.

Venkatesh also makes the distinction between the “University–wide” Day of Conscience and all the other Penn teach–ins, which he describes as “local,” and “on one specific issue.”

Student protest: Moratorium Day, October 15, 1969 (Vietnam War), 'guerilla theatre' | University Archives and Records Center

History PhD graduate Emma Teitelman (GR ‘18) does not share this interpretation. Emma says in an email that “the distinction itself seems to sanitize the politics of older teach–ins at Penn. Faculty and student organizations co–sponsored teach–ins not about abstract, academic questions, but rather about pressing social and political concerns of the moment [...] Because many of these teach–ins implicated Penn as complicit in, for example, chemical warfare and American imperialism, they were not exactly embraced as ‘university–wide.’”

Ira Harkavy (C’70, GR ‘79), a prominent student organizer in the College Hall sit–in that preceded the Day of Conscience, says that Teach–in 2018 is distinguished by the significant role the Faculty Senate played in its organizing. “In ‘69 I think faculty played a key role, and in this one faculty played a key role, but it was really led by leadership of the faculty senate,” he says. “They really took the lead, with the administration’s support.”

“Terms like teach–in are always plastic,” says Noakes. “But I think inherently if you have an event that’s staged by the administration it’s not a challenging event, it’s just a new way to teach, and I have no objection to it, but it’s not counter–hegemonic or counter–cultural. It’s actually something coming from the top.”

Meghna, the compass teach–in organizer, was also a member of the Student Labor Action Project, which in 2013 campaigned with Hillel dining workers who wanted better employment benefits. With SLAP’s help, the workers successfully unionized a month after they went public with their demands. Her experiences with SLAP and the compass teach–in meant that when she returned to Penn for her doctorate and heard about Teach–in 2018, she was skeptical.

“I’d always thought about teach–ins as something radical and revolutionary, that actually involved asking critical questions that shine a light on structures of power and also get to the politics of knowledge.” When Meghna attended the introductory event for Teach–in 2018, she says, “there wasn’t even a space to ask questions. Like, you had to write your question down on an index card.”

The historian Paul Lyons, describing Penn in the early 1960s, wrote that “The campus seemed to be dominated by Greeks, jocks, and the utilitarian pursuit of careers.” It’s a description that still rings true today—Penn, largely pre–professional and politically moderate, is not Berkeley. But that popular image fails to account for the decades of radical student organizing at Penn that in many cases gave way to concrete results. The selective history touted by the organizers of Teach–in 2018 obscures this legacy.

But those other teach–ins happened. It may not have been in the interests of the administration to recall them, but students like Meghna believe it is in the interests of Penn students to do so.

“It shows how important it is to talk about these questions about the purpose of knowledge,” Meghna says, “and we wanted to do our own teach–in just to really have a space for students to ask those questions and hear from people who are more oriented towards finding the truth, which isn’t always taught in university classrooms.”

Student protest against apartheid, to encourage Penn Trustees to divest in South Africa | University Archives and Records Center

In the promotional video for the “What the Fuck, Penn?” teach–in, Palmer reminded his audience of the legacy of student activism at Penn. “Back in our day, when we saw injustice in our schools, industries, and communities, we raised questions, we demanded answers, we fought back,” he narrates. “We taught each other, and those around us, that as students, we are able to think critically, and act on our beliefs.”

Palmer’s words are accompanied by black–and–white photographs of students marching with protest signs and crowded sit–ins in College Hall. In one, taken in 1970, after Nixon announced US military involvement in Cambodia, two students are looking out from a balcony onto College Green, where protestors are sitting on the ground from the Peace Sign to the entrance of Van Pelt Library, covering every inch of the grassy expanse. More students perch on building ledges and railings. They number in the thousands.

Naomi Elegant is a senior from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia and studies History. She is the Developing Features Editor for 34th Street.