Up a short flight of steps in the lobby of International House Philadelphia spans a row of artworks across the wall that, at first glance, seem to have nothing to do with each other. One is an abstract black–and–white monoprint that resembles a Jackson Pollock scatter–painting. Another is a colored–pencil drawing of “Satan,” who dons a black cloak with the words “No one escapes me” scrawled across it, the facial expression oddly resembling something out of a rage comic.

This diverse collection is Truth and Image, an open–call exhibition of artwork that “absorbs, captivates, transfixes, and ultimately delivers the viewer to newly imagined destinations.” On display in the East Alcove Gallery of the Lightbox Film Center until Dec. 15, the exhibit is a celebration of the building of worlds, tapping into unrestrained imagination to create fantastical and impossible things. Each “world” is conceived by a different artist, bringing a myriad of worldviews into one space. As visitors move around the gallery, their premises of what is normal are temporarily suspended. Within the boundaries of thin, black frames, space becomes relative, and reality distorts to fit the norms of each artist’s conceived world.

One work is a mixed–media collage titled The Collector II by Tom Herbert, featuring a Renaissance–esque man–bird hybrid set in the foreground of red forestry, horses, nude women, and images of history perching below a row of jars containing abstract objects such as cords and netting. Like much of Herbert’s other artwork, the piece revolves around deconstructing print images and reassembling them to create a narrative. The human figures incorporated in the collage appear mid–movement, many in a row as if indicating the passage of time, resembling the designs on Ancient Greek kraters. One can only theorize that Herbert has woven a mythology and a history unique to the world encompassed in The Collector II.

Another is Michelle Haberl’s digital photography print, Out to Pasture: A Sunfresh Saga I, a whimsical landscape of billowing white sheets suspended above a grassy, golden plain. The sheets are hung in ways that resemble empty hammocks, conveying a sense of absence that has the viewer on their toes and feeling slightly uneasy despite the artwork’s bright, peaceful surface. Haberl leaves room for viewers to interpret the story behind the scene: here is a world, whose presence of humans or cities or buildings has yet not been established. All that is shown is a web of ropes and sheets in a wide expanse of nature.

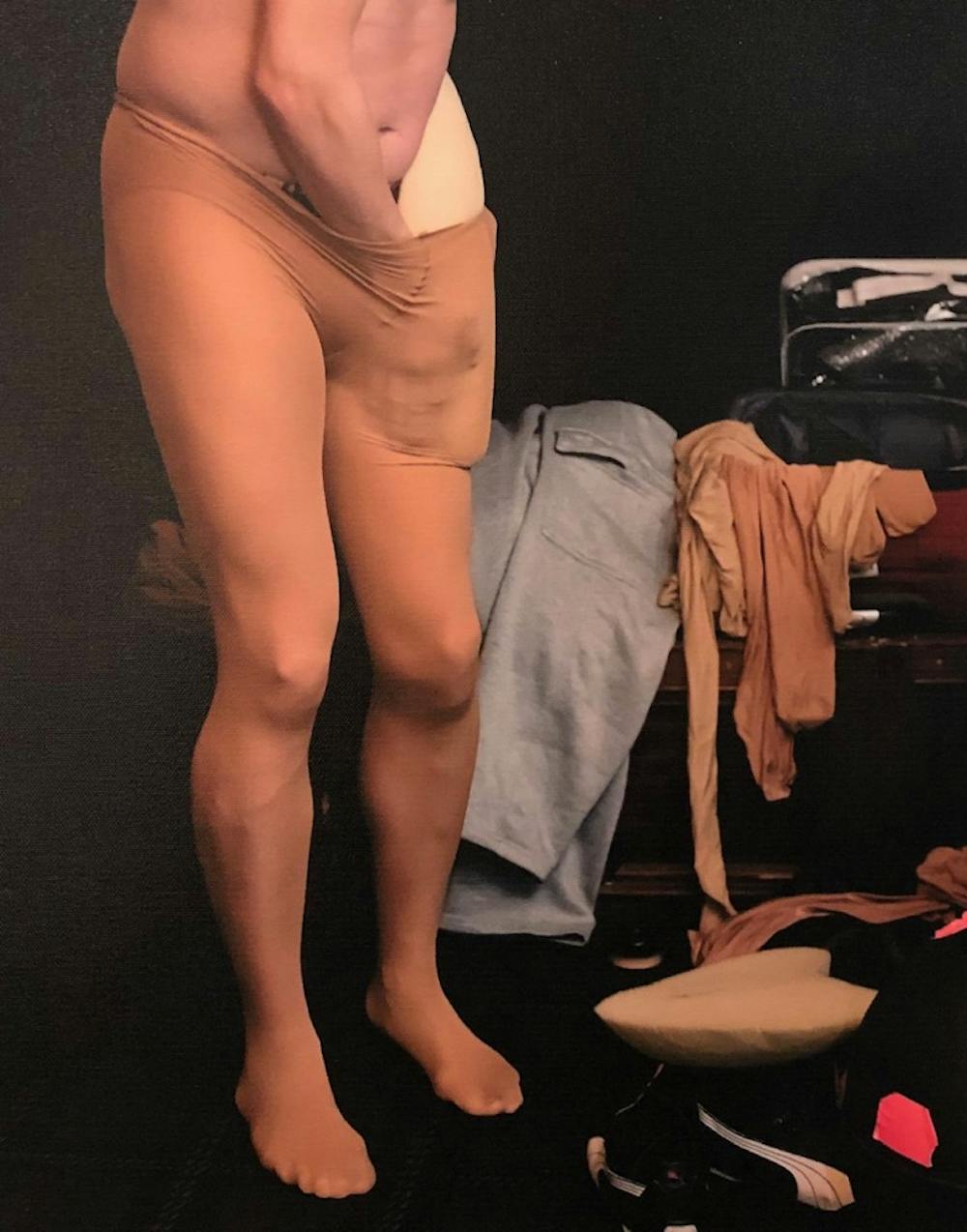

On the opposite side of the gallery is a print titled Lessons in Glamour III by Ellen Rosenberg. Taking on a more vulnerable tone, it depicts a drag queen in the dressing room in the midst of costume removal, captured mid–transformation. The photograph is flesh and fabric against a stark black background, almost resembling a painting at first glance. Rosenberg offers the viewer a glimpse into a space that, while real rather than fantastical, is to many viewers “otherworldly.”

As a whole, Truth and Image is a jumble of styles, artists, and intent. Beside each work, only the title, artist, medium, date, and price are listed, leaving the true meaning of each piece up to each individual’s take. The common thread that ties Truth and Image together is a suspension of reality and the power of visual imagery to create new and often supernatural realities. Although the exhibit inhabits only a small, quiet gallery, it contains worlds that expand beyond measure in the viewer’s own imagination.