On the face of the Allegheny SEPTA station is a mural of a woman pinching a palette in her left hand and a brush in the other. Behind her, a festival of tents and people and clowns and bagpipe music crowds the underside of the track, but she is intent on introducing the magic of color theory to the children who crouch beside her.

Every so often, the elevated railway screeches past, above the strip of pawn shops and hair salons, discount pizzerias and Toyota Camrys parked on the fringe of Kensington Avenue.

Omaya Torres (C ’21) remembers seeing “The Heart of Kensington” being painted. She recalls a childhood of blissful ignorance. “People generally assume that the neighborhood I grew up in is bad, which objectively I guess it is. Kensington is the center of the opioid crisis in Philadelphia,” Omaya smiles. “I lived through that but I didn’t know I was living through that.”

The ceiling of her Kensington home was “literally falling down, that’s not an exaggeration.” Sidewalks were perennially littered and many of the houses on her block sat abandoned. Despite the structural improvements that came with it, moving from Kensington, a predominantly black and Hispanic neighborhood, to Mayfair, an Irish–American one, put the then thirteen–year–old in “a bit of a crisis.” “I didn’t belong here. I didn’t fit into this neighborhood. This cultural shift, I hated it. I wanted to go back home where I’m used to.”

Over time, Omaya's anxieties subsided. Mayfair became home. Five years later she faced similar anxieties when she enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania. Starting school in University City came with its own culture shock.

Photo provided by Omaya Torres

Of the 3,699 admitted students in the class of 2021, 172 of them are from Philadelphia proper.

One of these Philadelphia admits is Amy Yeung (C ’21). Born at the Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Center City, Amy spent her youth between the Italian Market and East Passyunk, two blocks away from the cheesesteak rivalry of Pat’s and Geno’s.

Amy attended Julia R. Masterman Secondary School and spent her junior summer in Penn’s Young Scholars Program, an initiative for Philadelphia high schoolers to take college courses. It was her first visit to campus. “I didn’t realize there was an area like Penn in Philly,” she admits. There seemed to be some inexplicable distinction between Penn as an institution and Philadelphia as a city.

Amy places herself in the middle. "I went to an okay school downtown. I had the ‘good’ parts of Philly for most of life.” Still, “Penn socioeconomically is much different. I came into school, and people were wearing boat shoes. I was like, what the fuck are boat shoes?”

Joshua Snitzer (C ’21) attended Central High School, a public magnet school that yields more Penn admits than other Philadelphia-area schools. A 2017 report from the Associated Alumni of the Central High School of Philadelphia counts 48 students accepted to Penn. Despite such a high count of Penn admits per total student body of 2000 students, Joshua says that the culture at Central did not strive for the Ivy League.

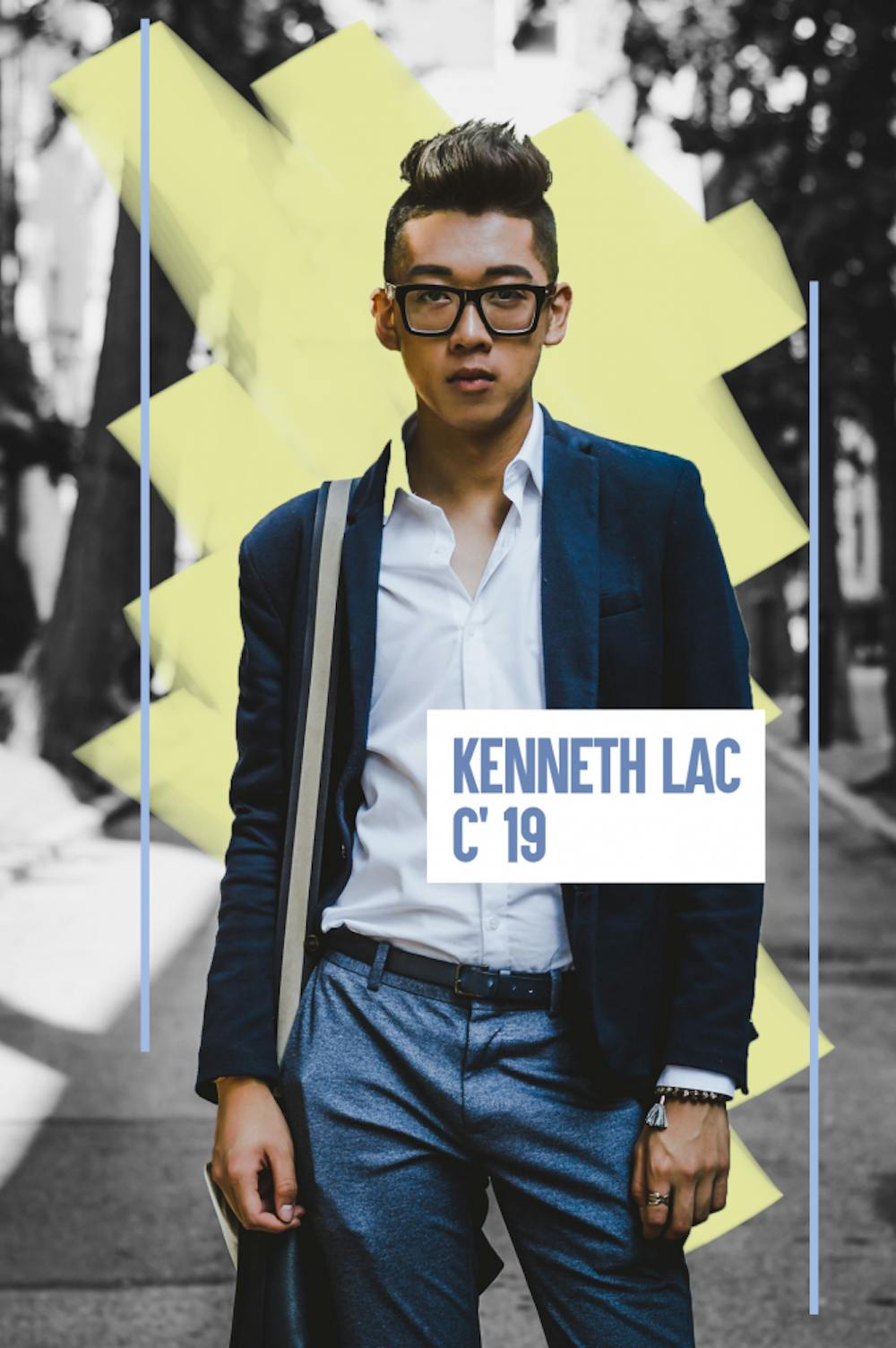

Provided by Kenneth Lac

“Penn was kind of seen as this place that was almost unreachable. A lot of people wanted an affordable college education and do well, because they were the first in their family doing it, which I think is very admirable.” Joshua notes that many college–bound Central graduates attend Temple University or the Community College of Philadelphia. For him, “Penn was aspirational.”

Omaya didn’t know about Penn until her junior year at the Philadelphia High School for the Creative and Performing Arts (CAPA). “The only other colleges that I really heard about were Temple and Drexel.”

Philadelphia is a nucleus of American history—the city of brotherly love housed both Continental Congresses and served as the nation’s interim capital. Philadelphia has been around since the first burgeonings of a United States; it’s where the Declaration of Independence was signed, where ENIAC was built, and where the Eagles savored the sweetness of a first Super Bowl win.

“I can’t explain why, but people who live here don’t want to leave here,” Amy says. “Even though it’s a huge city, there’s a sense of tight–knit community.”

By nature, Penn is transient. Students are Philadelphians for the duration of their schooling. There’s a fleetingness to Penn that feels mismatched with the long–standing traditions of the city it’s in. Once the degrees are complete, the diplomas delivered, only 10 percent of graduates stay to work in Philadelphia. The rest bid goodbye.

Kenneth Lac (C ’19) is another Central alum who never considered Penn growing up. “I didn’t know its prestige ‘til late high school. Public school kids’ framework of success is diminished, not at their own fault, but by institutions that deprive them of resources, that tell them they’re not good enough.”

Kenneth grew up in Northeast Philadelphia to an immigrant Chinese–Vietnamese family. He’s been trying to leave the city for a while now; it “just got boring to me,” he admits. The Philadelphia he knows is tough, never glitzy, and he’s seen how a “demand of food, destination, [and] entertainment,” driven in part by Penn students, has transformed and gentrified parts of Philadelphia into something he no longer recognizes.

Kenneth laments how many popular BYO destinations in Chinatown “were the places I used to go for real to eat, not to get trashed.” And the dishes Penn students tend to order are a “testament to [their] understanding of what Philly has to offer,” which is to say, there is more to Ken’s Seafood Restaurant than kung pao chicken.

Omaya is similarly frustrated, particularly by the way ignorance translates into geography. “A lot of people here are so reluctant to leave Penn’s campus and so reluctant to see the world beyond this little bubble, so whenever I hear someone say they’re not going past that street, it’s irritating.”

“It’s an unwillingness to learn, and that comes from the perception that Philadelphia is a crime city. I don’t think most people would dare to say it out loud, but when you call something ‘sketchy,’ when you use the words ‘ghetto’ or ‘ratchet,’ there are consequences and implications,” says Kenneth. “It’s mostly structured in some racial or socioeconomic discrimination and a lot of people aren’t willing to acknowledge that. And they freely throw those words out to describe certain neighborhoods that I call home.”

Photo provided by Amy Yeung

Kenneth acknowledges that many students come from backgrounds far removed from University City. Adapting to vastly different demographics can evoke culture shock, in the same way coming to Penn after growing up in Philadelphia came with a culture shock for many. “Your initial anxieties are valid,” he sympathizes, “but you have a choice to unlearn that and to realize the full potential Philadelphia has.”

Of all the murals Omaya has seen, “The Heart of Kensington” is her favorite—more for reasons of nostalgia than aesthetics. There’s a story in the bustle the image depicts, history on the wall it’s painted on. Omaya is currently taking an Academically Based Community Service (ABCS) course titled “The Big Picture: Mural Arts in Philadelphia.”

“Even in the most remote places—places that no one goes to, there’s a mural. There’s a mural in the corner of this building that no one ever sees, but it’s beautiful. And I love it.”

The class has allowed Omaya to better appreciate the nuances between neighborhoods, especially in the West Philadelphia area she never ventured to as a kid. She had heard of the “Penn bubble” before college and sought to “pop it, immediately” upon arrival. She’s grown closer to the city since her time at Penn, but it’s taken active steps.

Omaya is eager to stay in Philadelphia. Most Penn graduates will opt to do otherwise. Still, she hopes they learn to appreciate the city in the meantime.

Angela Lin is a sophomore from Eden Prairie, Minnesota studying Politics, Philosophy and Economics. She is a features staff writer.