Sterilized bacteria. Tooth enamel. Crystallized amino acids. Not your typical oil–paint–and–watercolor mediums. But in Anna Dumitru’s BioArt and Bacteria, these words can be spotted across almost every label. Running through November 24 at the Esther Klein Gallery, located on the first–floor of the University City Science Center at 3600 Market St., the gallery is an exemplification of how the British artist is contributing to an emerging movement known as BioArt that merges art and science, using living organisms and biotechnology to create meaningful artwork.

Bacteria are the invisible core of Dumitriu’s canon. They are sterilized and sewn into her fabric, documented on her magnified film, glazed in with her pigments, and tenderly adopted as her main source of both inspiration, both material and conceptual. As a BioArtist, Dumitriu’s mission is to visualize the relationship between humankind and the microbial world, especially concerning infectious diseases, through the combination of ancient art–making techniques and modern–day laboratory procedures. Her work delves into the messy history of medical ethics and disease treatment, creating a disarmingly visceral experience.

Upon entering the revolving doors of the gallery, viewers are immediately struck by Ex Voto, a shimmering conglomeration of aluminum that spans an entire wall. Hundreds of votive offerings are strung on a web of hanging ribbons—each has been created by an exhibition visitor, patient, scientist, or medic gin the spirit of documenting personal experiences with infectious diseases and antibiotic treatments. The work is dyed with various species of bacteria found in the gut as well as natural antimicrobial substances such as madder root, and the votive offerings symbolize wishes, both answered and unanswered, immediately drawing viewers into the wistful yet daringly optimistic world Dumitriu seeks to create.

Against the back wall of the gallery is an excerpt from one of Dumitriu’s key projects, the Romantic Disease Series. Here, a series of several pieces explore the history of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB), the bacterium responsible for TB that can be transmitted through tiny drops in the air. One piece, titled Rest, Rest, Rest! is a minuscule hospital bed made from cloth dyed with the extracted DNA of tuberculosis. The title and concept describe the rest-obsessed nature of tuberculosis treatment prior to the discovery of the Streptomycin antibiotic in 1943. Back then, patients were often confined to bed, made to follow strict daily regimes, and sometimes even had their lungs artificially collapsed for rest.

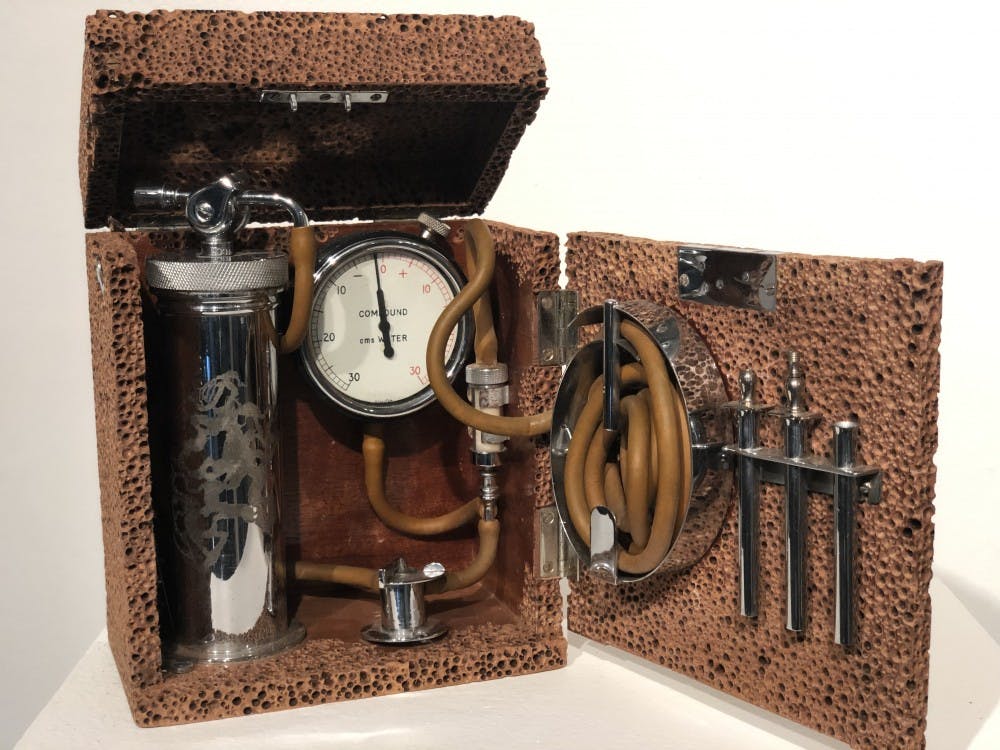

The next piece over, Pneumothorax Machine, is a spin on the machine originally used to collapse these patients’ lungs. The altered machine has a carved case, representing the texture of lung tissue, and an engraving on the metal, which illustrates a positive Ziehl-Neelsen sputum smear test used to diagnose patients with active tuberculosis. Overall, the Romantic Disease Series seeks to inform and contextualize rather than sway, and each piece speaks for itself without delving into controversial territory.

In another corner is one of the exhibition’s staples—an alteration of clothing titled Make Do and Mend. The piece is a wartime women’s suit marked with the label “CC41” for “Controlled Commodity 1941,” representing the scarcity and need to ration commodities during World War I and the year in which penicillin was first used to treat a patient. Each hole and imperfection in the suit has been patched with pink silk E. Coli–stained silk, the bacteria itself genetically modified to remove a penicillin–resistant gene. Here, Dumitriu has used modern technology to regress the organism to its pre–antibiotic state, carefully reflecting on the growing menace of antibiotic resistant and how humankind might deal with it in the future.

Dumitriu’s work may play with living organisms, but its true medium is none other than time. Each piece picks apart the nuances of history through the lens of disease, microbes, treatment, and war across each century. A trip to the Esther Klein Gallery this November will not only be an opportunity to unwind and enjoy art, but also a perspective–shifting journey that will change the way you view the medical past.