Another rock & roll legend has passed. Marty Balin, frontman and founder of Jefferson Airplane and Jefferson Starship, left us on Sept. 27, 2018. He was one of those few artists who managed to carve out a new path for music and culture. He stood at the vanguard, carrying the flag of psychedelia, a sound and philosophy that would come to change the world. Now that he’s gone, we may continue the trend of blaming an artist’s death on the year and making his tragedy our own; or we can take a step back and try to honor him through his legacy. I favor the latter.

From the second half of the 1950s, Beat Generation writers like Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg began writing on and about drugs, raising awareness of stimulants and hallucinogens. This trend continued into the early 1960s, when the idea of an altered consciousness started to really take off. It was during this time that novelist Aldous Huxley wrote his infamous essay "The Doors of Perception," in which he described, in excruciating detail, his experiences with interconnectedness and self–transcendence after taking two–fifths of a gram of mescaline.

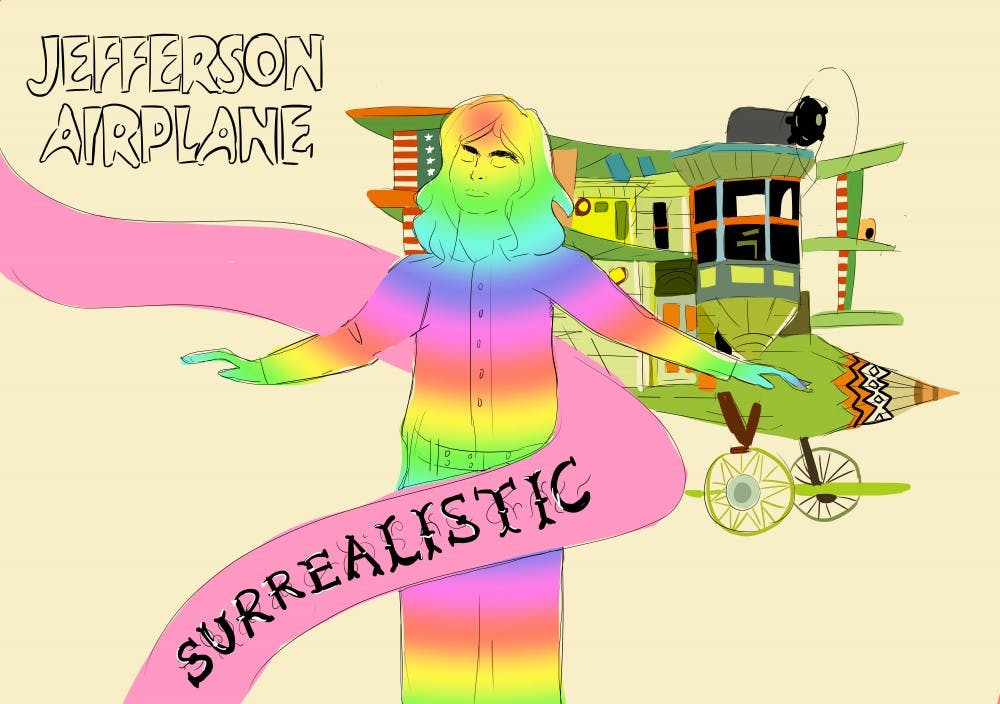

Jefferson Airplane was founded in the context of a budding subculture that revolved around the usage of hallucinogens to expand the reach of the mind. They explored the sounds that best explain and mimic the state of an altered consciousness and, in doing so, they became one of the first bands to play what we now recognize as psychedelic rock and psychedelic folk. "White Rabbit," their first hit single, portrays some of the characteristics that would come to define the genre. The song features “exotic” instrumentation in the shape of a Spanish rattle, a drone–like backing rhythm and allusions to Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, which served as a medium to convey their surreal experiences on psychedelic drugs, while also bypassing radio censors.

As Jefferson Airplane grew in popularity, the sounds that defined the often misconstrued genre of psychedelia began to solidify in the public’s subconscious. Pink Floyd’s dissociative song structures, Jimi Hendrix’s deconstruction of harmonic conventions, The Doors’ (curiously named after Aldous Huxley’s aforementioned essay) Jazz–infused floating synths, and The Beatles and Beach Boys’ usage of modal melodies, surreally whimsical lyrics, guitar feedback, reversed tapes, and “exotic” instrumentation all helped mold the genre into what it is today.

All of these forces in the musical world came together in 1969. That year, Jefferson Airplane would be the headliner in two key historical music festivals, one of which would mark the climax of the psychedelic movement in all its glory, while the other would mark the beginning of its decline. Drug culture and rebellion became one and the same in the second half of the 1960s. The New Left, hippies and Civil Rights advocates all converged at the Woodstock Festival of 1969, a celebration of peace and opposition, and a massive success for the counterculture. However, in a failed attempt to replicate that same sense of communal coexistence, things turned sour at the Altamont Free Concert in California, where racial tensions, the unfortunate hiring of a biker gang as security, and widespread panic resulted in the death of four innocent lives. What had previously been a place for interconnectedness between all members of the counterculture became a place of division, and the ideals that held all of its factions together were put into question. This marked the decline of psychedelia as a culture and as a genre.

Nevertheless, the influence of the movement lived on in future generations, mainly in the shape of progressive rock. Many of the bands that started in psych rock moved on to prog, as was the case with Pink Floyd and Jefferson Airplane’s reincarnation in Jefferson Starship. King Crimson’s "21st Century Schizoid Man" best exemplifies the influence of psychedelia in the progressive rock era. One that would reach across borders and lay the groundwork for German krautrock and Brazilian tropicalia.

The influence of psychedelic music also had a great impact on black musical tradition. Jimi Hendrix’s popularity is partially responsible for the creation of two subgenres: psychedelic soul and psychedelic funk, also known as P–Funk. When it comes to psychedelic soul, it brought with it the rebellious sensibilities of the 1960s counterculture, and bands like Sly and the Family Stone demonstrate how the philosophy of psychedelia lives on in their music, which is layered with social commentary. And when it comes to psychedelic funk, George Clinton is the man that defines the genre. His influence was so powerful that the etymology of the term P–Funk is debated between stemming from psychedelic funk and Clinton’s sister–band collective Parliament–Funkadelic, both of which incorporate the oscillating electric guitar licks that they inherited from Hendrix.

And now, we’re seeing yet another revival of the sound that Marty Balin helped create, in the shape of neo–psychedelia. This psychedelic renaissance has kept the heavy sound distortions and references to trance-inducing experiences typical of the 1960s expressive style. So, next time you’re listening to The Flaming Lips, Animal Collective, Deerhunter, Tame Impala or even MGMT, know that Marty Balin helped set the stage for their modern classics.