“First, a soothing word.”

The opening sentence of the first–ever 34th Street Magazine is this promise. Below a shakily hand–drawn masthead, the inaugural letter from the editors prefaces the new magazine. On October 11, 1968, while Penn’s campus was hungover from the Summer of Love, swarming with anti–war protests, and watching the newly–released 2001: A Space Odyssey, Street entered the “renaissance of non–ennui.” The editors hoped to “elicit articles from members of the community who have had little or no previous outlet in print” and offer a “compleat” entertainment guide in each issue.

And with that letter—wrapped in a cover of an enormous pig sniffing a police officer’s cap—Street entered the Penn community. It had been conceived by Charles Krause (C ‘69), known then as Chuck, who ceded the position to Bill Mandel (C ‘69) after he was named Editor–in–Chief of The Daily Pennsylvanian. Mandel, who had also applied for the top DP spot, accepted, and began what would become a decade–long tradition of DP–hopefuls being given control of Street as a consolation prize.

“It was a life,” said Bill Mandel. “Not a lifestyle.”

34th Street logos through the years.

Mandel spent so much time in the DP office that he didn’t graduate from Penn, missing one Spanish credit. Although he enjoyed a career in journalism like many Street alums, he did so without a Bachelor’s degree.

The first issue established boundaries that Street would redefine and push against over the next 50 years: it was a magazine by, but not necessarily about, the Penn community. It primarily covered entertainment, but it was also political (“Don’t Oink Back” was its first feature). The writing had flair but wasn’t obnoxious (okay, sometimes it was obnoxious). Street began as a supplement to The DP to expand its arts coverage and explore feature–style writing. In addition to the Art, Cinema, and Drama sections, Music was divided into “Oldtime” and “Secular.”

Street's October 11, 1968 issue, "Don't Oink Back." Edited by Bill Mandel.

“Subtle hatred of University’s guts is displayed by neighbors,” Street wrote in its first issue about Penn’s relationship to Philadelphia. In the next handful of years, Street would interview Kurt Vonnegut, the Jerry half of Ben & Jerry’s, Jamie Lee Curtis (pre–Activia), and the New York Times Crossword Editor.

“Those were crazy days,” Mandel recalled. “We’d run around, we’d stay up all night [...] I’m sure it’s the same now.”

Arnie Holland (W ‘71) was a freshman when Street began in 1968. He had been gunning for a top spot in the DP’s executive board, but was offered the Street position instead.

“After a moment’s surprise, I took to it like a duck to water,” Holland said. He was passionate about music and movies, and inspired by publications like The Village Voice and The Boston Phoenix.

“The war influenced everything because we didn’t know if we’d get drafted after college,” Holland said, recalling listening for his draft number on the office radio. While working for The DP, he covered the anti–war movement at Penn and elsewhere; he wrote about getting tear gassed at a Cleveland protest.

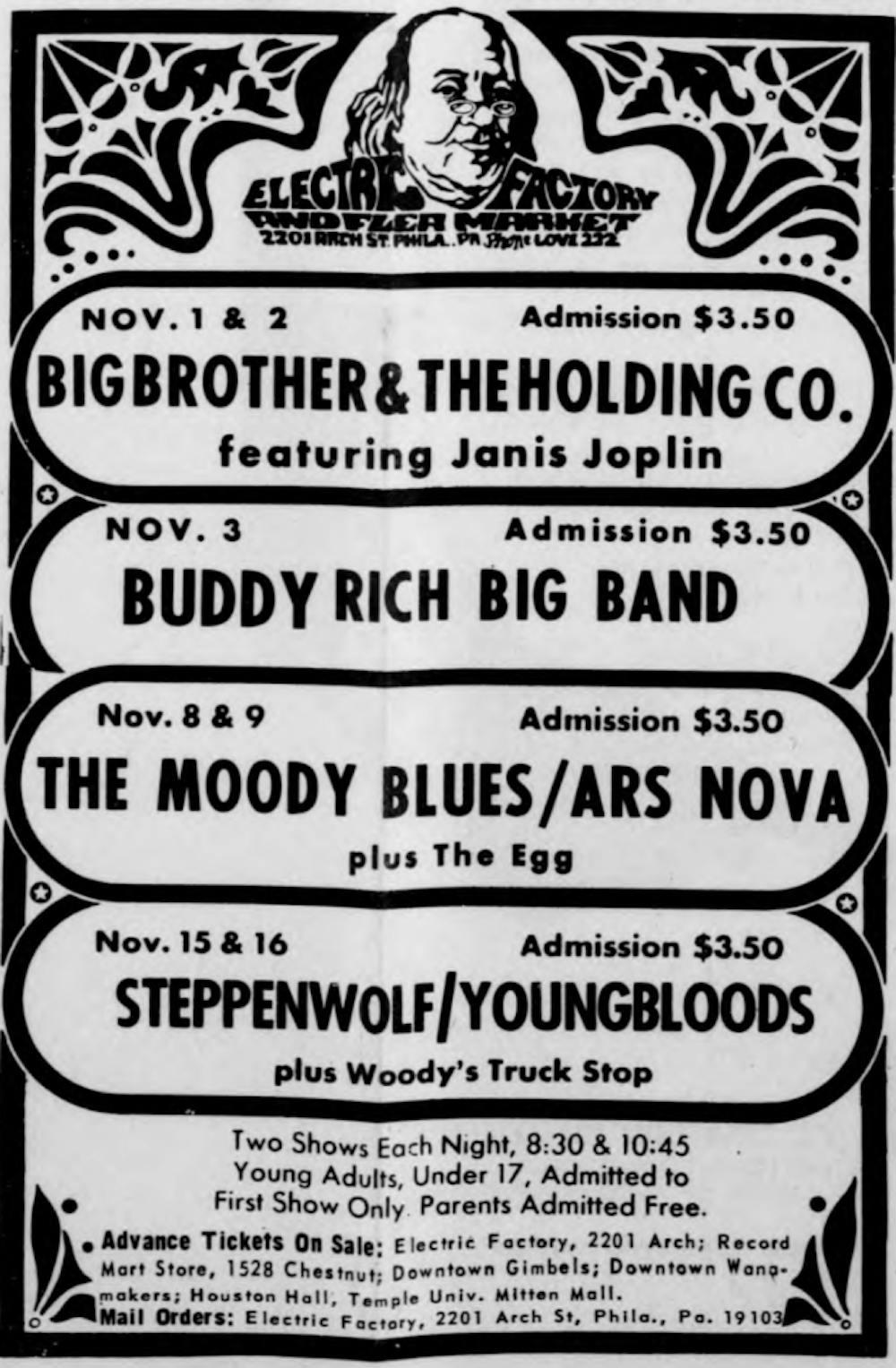

By contrast, Street was a way to flirt with political subversion while getting free albums and concert tickets. Managers sent writers passes to Philadelphia’s Electric Factory or the Spectrum Theater in exchange for reviews of Van Morrison, Janis Joplin, Cream—whichever musician was touring in Philadelphia.

Electric Factory poster from 1969 advertising a Janis Joplin show.

In its review, Street reported Janis Joplin was “wailing, moaning, screeching, stomping, jumping, crashing, twisting, swinging and tearing herself and 17,000 others to pieces.” The deluge of shows led one Street writer to speculate in an October 1968 issue that “maybe Philly isn’t so dead after all.”

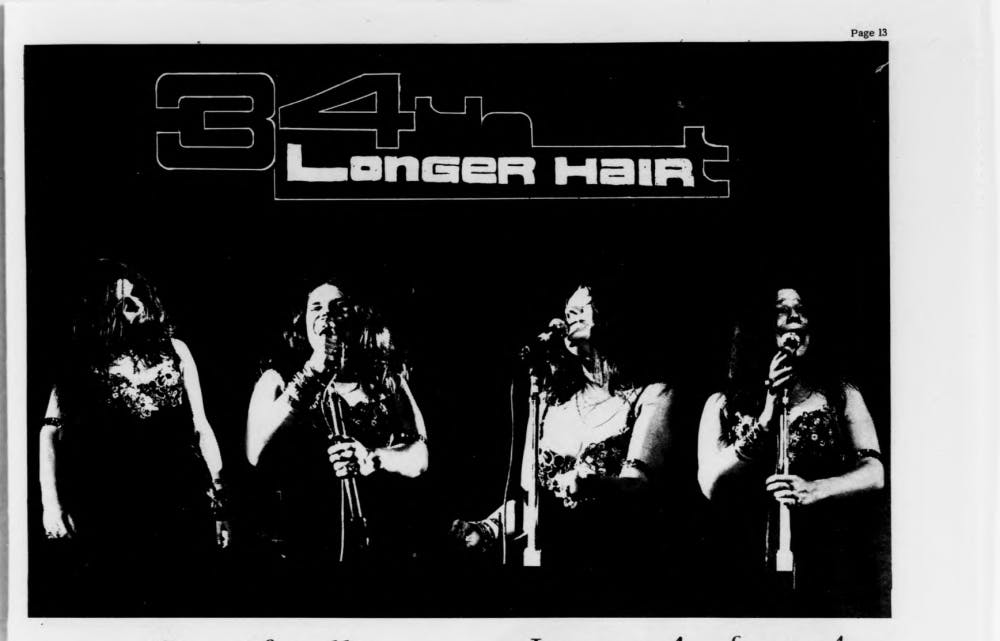

Street covers a Janis Joplin concert in its Music section, then referred to as "Longer Hair."

Just assembling the paper was more laborious in the ‘60s and ‘70s. A bullpen of manual typewriters were centered in the Street office. To print on a continuous page, writers would glue stick sheafs together. As Editor–In–Chief, Arnie laid out the pages into the massive printer on production night, lining the type to his T–square. Arnie shouldered the five– to six–hour process each week. He left the printer’s office at 3:00 or 4:00 a.m. and drove back to campus before dawn (except the night his car was stolen).

Just a few years after Mandel’s “99% male” DP office, women were breaking through the ranks. More writing opportunities and the promise of arts coverage offered women a previously uncovered campus niche. Early female writers, like Valerie Wacks (C, W ‘73) and Claudia Cohen (C ‘72), found a voice in Street.

“She and I would sometimes go to events together. They weren’t really dates because she was very clear to me she wanted to marry a rich guy,” Arnie said about Cohen. “Which is exactly what she did.” Claudia Cohen Hall on campus, is named after her.

Following alt–weeklies in other cities, Arnie spearheaded distributing Street across Philadelphia. After recruiting a fellow Penn student to drive, he mapped out distribution points around the city: record stores, malls, other college campuses.

The plan fizzled out, but it created a precedent for Street to be more Philadelphia–facing than other Penn publications, a trend it has continued to alternately embrace and buck during its run.

Still, the oldest issues reflect many of the same topics that Penn students still chew on in print. “Higher education once prepared young people for life, whereas now it prepares them for jobs,” a Street editorial railed in 1969, arguing a Bachelor’s degree was the cultural equal to the “‘U.S.D.A. choice’ stamp on meat leaving the Chicago stockyards." Sound familiar? Probably.

In its first decade, Street lived entirely in the DP’s shadow. Mitch Berger (C, G ‘76), Co–Editor with Lee Levine (C, G ‘76) in ’75, decided to “take on” 34th Street after a year as a top DP editor. He describes it as a resuscitation effort.

“I don’t think anyone on campus read it,” Berger recalled. “It was an in–house organ of the Philomathean Society.”

At that time, Street covered a narrow band of “obscure, avant garde” entertainment that ranged from student poetry to the 677–page biography of French statesman Charles Maurice de Talleyrand–Perigord. Too obscure for the casual Penn audience? Street didn’t think so: on April 18, 1974, Street printed a book review of the “fast–reading” volume by Jean Orieux, opening the article with an excerpted exchange between Talleyrand–Perigord and Countess Sophia von Kielmannsegg and anointing the book a “massive contribution to the controversy.”

Berger’s vision for the magazine was more Philadelphia–focused, summed up by the credo, “Don’t be so insular, don’t be closed in, leave camps.”

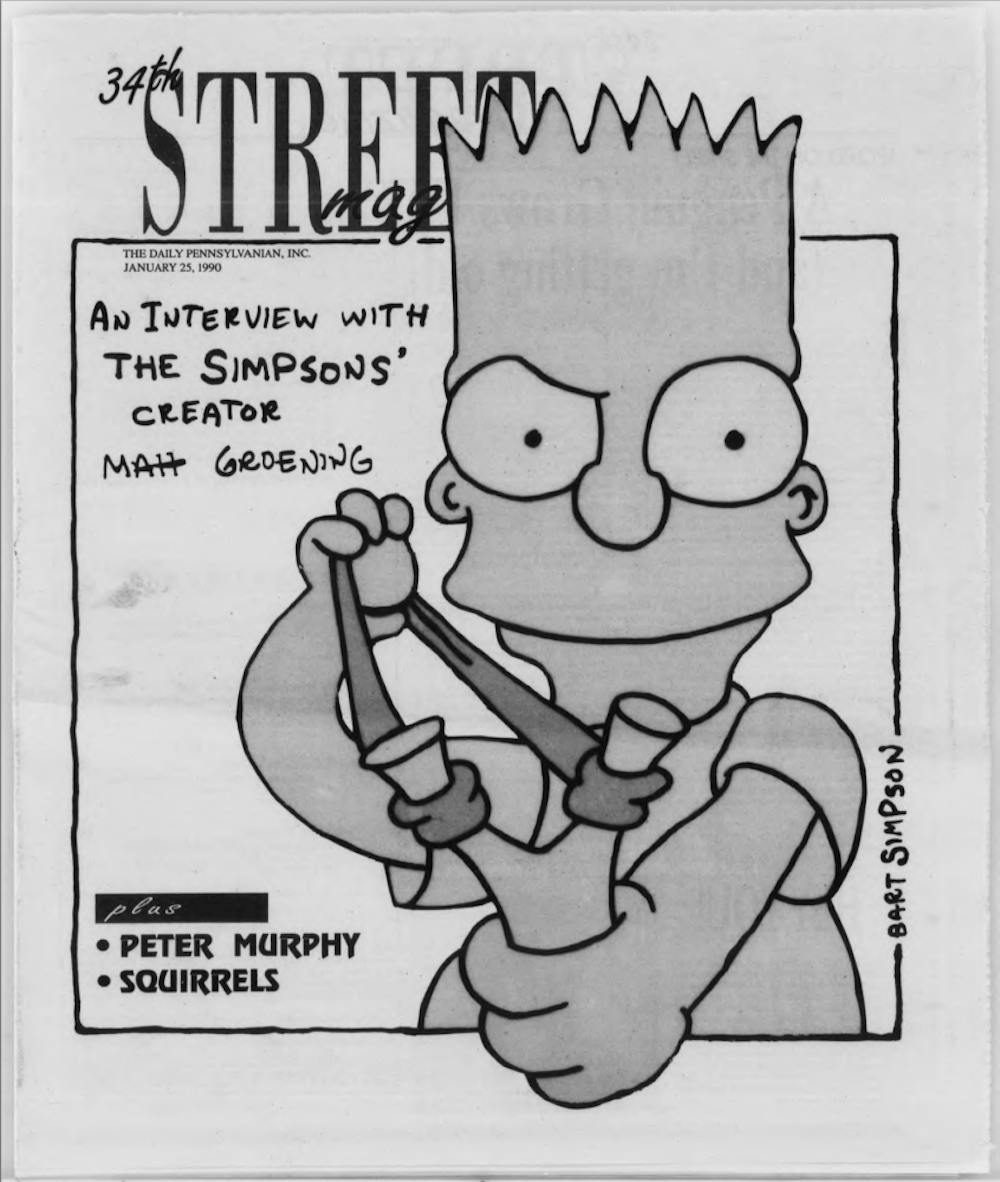

Street's January 25, 1990 interview with Matt Groening, the creator of "The Simpsons."

As Philadelphia approached the bicentennial, the city was shifting from a backwater “cheesesteak kind of city” to a destination for consumable culture. Inspired to record the new opportunities for student revelry, Berger injected new voices into the paper. Street’s backbone became ongoing columns written by four campus men, including Buzz Bissinger, current Penn professor and Pulitzer prize winner. Influenced by Gonzo journalism, the men penned self–referential columns on topics such as local martini fare (“The offerings vary in taste from rancid to very potable”), police brutality against black Philadelphians, and fantasies about riding a silver stallion down Locust Walk.

In 1975, Street’s namesake was razed by the University. Sergeant Hall, on the eponymous 34th and Chestnut Streets, was a former apartment building–turned–women’s–dorm–turned–DP–office. Since its demolition, The DP and Street have lived at 4015 Walnut Street, a former fur storage facility.

As Co–Editor with Lu Anne Stewart (C ’77), Charles Service (W ‘77) created the first beat reporter positions in 1976. It was the first time the fledgling publication didn’t source its talent by siphoning off of The DP.

The old issues show how Penn stereotypes have changed over time—and remained the same. In 1976, a Street cartoon featured a male pre–med student clobbered by a Gucci bag, explaining that Penn women, “1) entice their mates, 2) abduct them, 3) ship them back home, 4) where the women’s daddy’s [sic] pay the postage due.”

Even so, some coverage was “a world different in 1976 than 2018,” according to Service. For instance, an article about gay students on campus called “Can Gay Mean Happy?” prompted a homophobic letter to the author written on used toilet paper.

Almost ten years after its conception, Street was going through a growth spurt and refining a style and tone recognizable to today’s Quakers.

Howard Gensler (C ‘83), the Co–Editor in 1981 with Aphrodite Valleras (C ‘86), confirms Street “started with a political bent” but had retooled to a mostly entertainment focus by the time he assumed the top position. As an editor, he saw much of his role as a curator for how students should spend their entertainment budgets.

“We didn’t take some of it that seriously,” Gensler admitted, remembering the one–liners hidden in the pages, listing fake movies, and the inaugural joke issue’s front page headline: “Is Pope Coke Fiend?”

"Is Pope Coke Fiend?" cover story from February 25, 1981 joke issue of Street.

By the mid–’80s, the erudite references had been largely leached from the pages, with a new emphasis on more accessible entertainment. In contrast to its review of the encyclopedia–sized French biography, Street covered a 1984 “beer–drinking guide” written by three “Yalies.” Capitalizing on the local cult meetings, a student reporter went to consecutive Hare Krishna and “Moonie” (Unification Church) meetings to compare the free food offered to cult members because “they may well invite you to dinner in hope they’ll convert you to their religion.”

“The Krishnas didn’t stop feeding me until I felt like the fat man from Monty Python’s Meaning of Life. But the food and the service was excellent,” concluded the writer, giving the Krishnas four stars and the Moonies just three and listing the mealtimes and transportation routes for hungry students.

The irreverent writing didn’t impress all readers: an Annenberg staff member wrote to Street after the “Soul Food” article to call its “casual treatment” of cults’ indoctrination efforts “patently unacceptable.” A College graduate of ‘85 inquired in a Letter to the Editor:

“Why do you feel it necessary to flay certain musicians and filmmakers with non–funny one liners?”

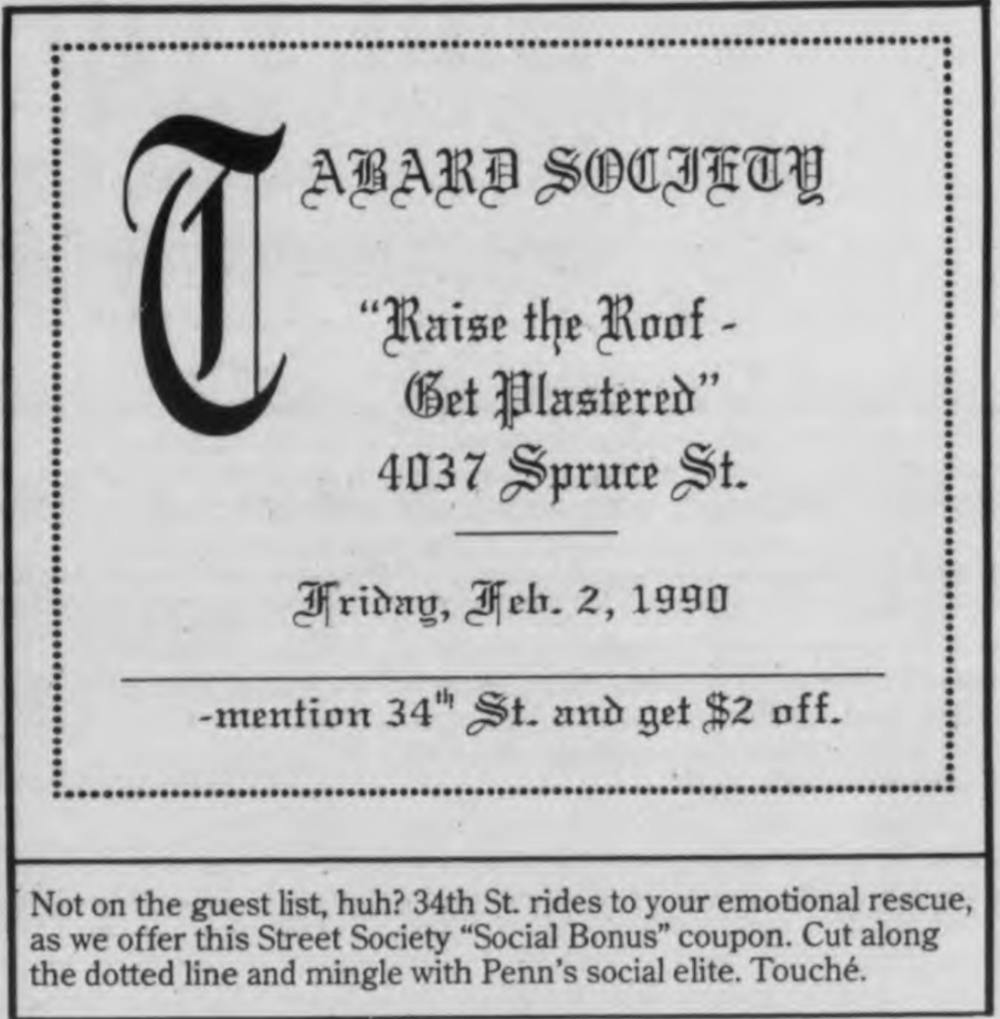

As Street entered the ‘90s, it was refining a breezy, infotainment style a la Entertainment Weekly. Street printed a coupon for a Tabard Society party in February 1990, offering “emotional rescue” for students excluded from the guest list. During the collapse of the Soviet Union, Street—ever abreast of current events—reported: “In a very big country whose red flag has tools on it, a lot of people got together to say they want to have lots of different parties rather than one big one.”

Humorous coupon created for a Street Society article in 1990.

Inspired by publications like The A.V. Club and Spy magazine, Street entered the ‘90s with takes on mostly–mainstream “funny goofy pop culture snarky bullshit,” according to Matt Selman (C ‘93), Editor–In–Chief in ‘92.

In a 1990 issue dedicated to fashion, students pose in moody black–and–white shots wearing lycra tennis suits, rayon dresses, and strappy sandals. The gossip column, Street Society, reported weekend misadventures of Penn students using their full names (not as chilling in the pre–Google era). An older incarnation of the now–dead Round Up, Street Society was mostly preoccupied with who vomited at Greek events.

"Urban Legend," the January 23, 2003 issue of Street that documents the rise of Urban Outfitters.

“Let me spell it out for you. P–A–R–T–I–E–S. You gotta have more parties,” the Street Society columnist, pen name Roy G. Biv, declared. “I can’t subsist on the porage [sic] you folks pretend is a social life. And frankly, I’m not getting enough free alcohol.”

“I always pretended everyone cared and read it,” Selman said, even when “hundreds” of unread copies in garbage cans each Thursday said otherwise. Raucous meetings with lots of laughter were a bigger draw than circulation numbers, anyway.

Some coverage was “the fluffiest fluff ever to be puffed out,” Selman recalled.

A photo of two dogs having sex cost the magazine advertisers. Sometimes the deadpan style was funny. Sometimes it was needlessly mean. Even so, the magazine interviewed The Simpsons creator Matt Groening, the band Weezer, and wrote features on fake IDs and clubbing in Philadelphia.

"Under Wraps," cover story from February 12, 2010 issue of Street.

By the mid–aughts, Street was still operating like an alt–weekly for West Philadelphia. The staff was “very cool, no one was in Greek life,” according to former Managing Editor and Editor–In–Chief Julia Rubin (C ’10).

Rubin took on the role of Managing Editor and Editor–In–Chief back–to–back—a two–year stint that launched her career in digital media after graduation.

“I spent an incredible amount of time in that office,” Rubin laughed, recalling the windowless room and dirty couch and Monday night pizza. “So much time. But it made me feel really adult.”

While the 2008 recession was speeding the shift from print to online media, blogs flowered on the unprofitable internet. Following schools like Columbia, NYU, and Penn State, Street’s then–Editor–In–Chief Kerry Golds conceived Under the Button, originally a Street blog. The original concept was an offshoot of Street’s old Highbrow section—current events with snarky commentary, campus gossip, and quippy observations.

"The Dividing Line," cover story from April 23, 2015 issue of Street.

As the recession hit print media especially hard, advertising dried up. Rubin remembers short 16–page issues: “It would be like, ‘You guys have a lot of pages because we don’t have ads, but this issue is going to be very few pages because you don’t have ads.’”

As Street entered the 2010s, the staff, led by Rubin, who was a sorority member herself, got “more Greek and, dare I say, mainstream.” Coverage shifted more exclusively to Penn students, birthing landmark Street projects like the sex survey.

The current iteration of Street will be swept away as surely as new headlines push down the old ones. New names on the masthead, new leadership, new ideas for ways to package Penn will replace the ones now. That isn’t unusual for anything at Penn, where the shelf life of involvement is no longer than four years. But unlike most extracurricular groups, there's so much output—50 years of archives. Physical evidence that demands to be touched and paged through and revisited to see how Penn has changed.

But first, a soothing word.

*An earlier version of this article stated that the Editor–in–Chief of 34th Street who started Under the Button was Kerry Jones. The article has been updated to reflect that the editor's name is Kerry Golds. 34th Street regrets these errors.