A couple of years ago, a friend and I fell victim to a harmless fixation on Salinger’s storytelling. We were sixteen back then and in hindsight, that obsession was a sort of collective mania that we were actually late to join. Late, I say, because it wasn’t The Catcher in the Rye that we read over and over. The culprits in our case were Salinger’s out–of–print publications, a collection of 22 short stories that traced his legacy starting from his time as a student writer at Columbia University to his later success in The New Yorker.

As I read through the stories in Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties, I inevitably drew some parallels to those early days of short–story reading, and to the author that made me fall in love with a genre that is, much too often, not given enough credit. By the time she arrived at Penn as writer–in–residence in 2016, Machado had already built a career that would make others envious: her stories, published in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, and Guernica, were already praised in the journalistic and literary fields.

This is why, when I try to ask Machado about her first book, I hesitate for a moment—“debut,” so suggestive of inexperience and clumsiness, doesn’t quite cut it. Her Body and Other Parties was a finalist for the National Book Award, and has won numerous accolades since its release in October 2017. It is already booked to be translated in 17 languages. Reviews were so stellar and moving that some—she told Penn Today in late 2017—made her wife cry. And now, as reported by Vulture in June, the stories are to be adapted into a “Black Mirror–esque” anthology–style TV series. It is set to premiere on FX, along shows such as American Horror Story and Atlanta.

“A couple of the stories, I think, are pretty straightforward to adapt,” says Machado, but her statement will most likely leave readers who are familiar with her work questioning. Granted, most of her tales—with a chronological plot, some characters, and a clearly defined setting—are traditional. Her writing style is anything but.

Personal interventions, multiple plot lines, and seemingly unconnected events—such is Machado’s oeuvre, which could, interestingly enough, pass as non–fiction at any time. It’s a unique experience, Her Body and Other Parties, a book in which words are not just instruments, but one of the centerpieces in a composition so masterful, so harmonious, it resembles poetry.

But there’s one key recurring motif in Machado’s stories—one that, due to FCC restrictions, is likely to strip the TV adaptation of a similar impact: sex. Though ubiquitous throughout the collection, sex is crucial particularly in the second story, “Inventory,” which is essentially a list of descriptive sexual encounters meant to draw a parallel between the physical and the emotional through sex with men, then women.

“I think [sex scenes] are really fun, and I think they have a lot to tell us about our assumptions about gender and sexuality,” Machado says. “I'm not putting them in there to be like ‘whatever, I included a sex scene.’ I think that it's important to have it in there for some reason. It's not just for kicks.”

Indeed, it’s hard to imagine the stories in Her Body and Other Parties without the sex. Machado’s words are graphic, powerful, and cleverly provocative. Her associations—she writes of an orgasm, “I felt like a guitar and someone was twisting the tuning pegs and my strings were getting tighter”—are meant to incite, to shock, and to challenge the male view on women’s sexuality.

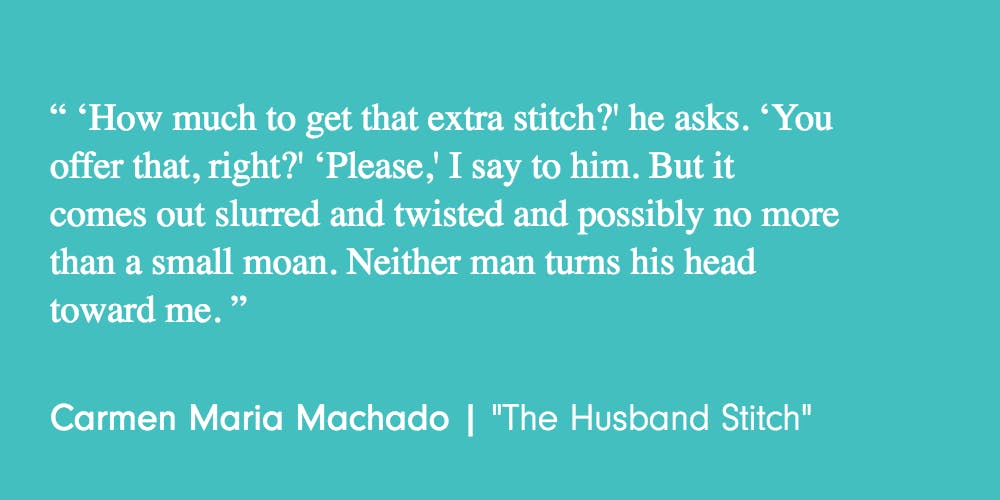

“The Husband Stitch,” the collection’s opener, was called “the strongest and scariest story” for a reason, and it is what probably inspired the association with Black Mirror. A feminist retelling of “The Green Ribbon” shouldn’t ever have had to be dystopian; but in 2018’s post–Harvey Weinstein world—Machado’s book was published only two days before his sex offenses were exposed by The New York Times—such tales don’t even seem fictional anymore.

Had I read “The Husband Stitch” in a different context, Machado’s story would have probably passed as another—yet nonetheless shocking—fictitious tale meant to draw attention to the oppression and powerlessness of women, even in the modern world. But it was only a couple of days before I started reading Her Body and Other Parties that I came across a short Buzzfeed article detailing the practice. It was so disgusting it made me screech. What is even more disgusting is that it is still relevant.

Written as a first–person narrative, “The Husband Stitch” tells the story of a woman whose only request from her boyfriend—then husband—is not to meddle with the green ribbon she wears around her neck. The man keeps asking why. The woman still says no. In spite of her protests, he tries and tries, until she finally gives in and he finds out that the secret she kept so deeply was meant to protect both of them.

And the story is interlaced with anecdotes that could be turned into individual short stories at any time. Such as the one about “a girlfriend and a boyfriend [that] went parking,” and who presumably are killed when the boy refuses to leave, even after the girl tells him that she is uncomfortable. Machado ends with the line “I’ve forgotten the rest of the story.”

Anecdotes like the ones in “The Husband Stitch” are difficult to even incorporate into a story that’s already so short to begin with. Machado herself is unsure of how it can be done:

“I'm always really interested in the way that people adapt books that feel unadaptable. It's almost like translation—you're taking the thing that you know, and you're trying to fit it to this new place in a way that's meaningful and interesting. That's what's so cool about it.”

Machado also knows other stories are likely to delay production. She describes “Especially Heinous”—the longest, novella–sized story—as “basically a Law & Order: SVU fan fiction. The structure of it is really unusual, and I could see that being a challenge for someone to adapt.”

In “Especially Heinous,” Machado goes through twelve seasons of Law & Order: SVU episode by episode. But naturally, there’s a twist. “Closure,” which premiered in January 2000 and is about a woman who tries to remember what her rapist looks like, is retold simply:

“It was inside of me,” the woman says, pulling the bendy straw out of shape like a misused accordion. “But now it is outside of me. I would like to keep it that way.”

The attention Machado pays to women’s autonomy—or lack thereof—is second only to the collection’s focus on inclusion. Challenging assumptions about race, gender, sexuality, and body–image is what Machado is particularly concerned with. “I'm thinking about the diversity of this book, and I want to maintain that. This book is obviously incredibly queer, and I also feel like there’s a temptation to put that white, skinny polish on it.”

“I already told [the writers]. I want bodies that fall outside of the traditional…You know, I want fat women, and I also want lots of women of color. I don't just want a bunch of skinny white ladies.”

That is Machado’s one and only request of the show’s producers. Other than that, she says she is “really excited for whatever happens. Even if they seem hard to adapt, I'm excited to see what all these other artists and other thinkers or do with the material.”

Carmen Maria Machado’s book can be purchased online on Amazon, or on the Barnes & Noble website. Read Street’s feature on Carmen Maria Machado from March 2018 here.