Bill Mandel was a Founding Editor–in–Chief of Street from May 1968 to May 1969 and DP Associate Editor from May 1968 to May 1969.

This piece is part of a series of personal narratives written by Street alumni in order to celebrate the 50th anniversary of 34th Street.

Two things I noticed my first day at Penn in September 1965 were stereo speakers stacked in multiple dorm room windows playing “Satisfaction” by the Rolling Stones–which had just been released—and a bunch of fraternity brothers roughing up students protesting the Vietnam war in front of College Hall. A small crowd shouted encouragement. In September ’65, being antiwar was sufficiently anti–American to deserve a stomping.

Then change came, fast enough to open minds and change hairstyles: Yearbook photos for the Class of ’69 were taken in the fall of 1968. All the guys had short hair. By the spring of ’69, when the yearbooks were distributed, the head shots from just eight months earlier were relics. All the guys now had long hair. (Apologies for the gender–imbalanced reporting. The change was simply easier to notice among the men.)

The summer of 1965 saw a racial uprising against police oppression in the Watts section of Los Angeles, followed by 1967 rioting in Detroit, Newark, and Milwaukee. The next spring, Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated just a few weeks after appearances in Philadelphia. MLK was in town to support a garbage collectors’ strike (I was lucky enough to draw the interview assignment for The Daily Pennsylvanian). At The DP’s invitation, RFK had spoken to a roaring student audience at the Palestra. So had U.S. Sen. Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota, whose insurgent antiwar campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination helped drive President Lyndon Johnson from the race. Johnson triggered a delirious campus Rowbottom when, in a surprise, he ended a March ’68 speech by announcing he wouldn’t seek reelection.

That August, as the whole world watched, police attacked young antiwar protesters at the Democratic National Convention—bloody live war coverage not from the jungles of Southeast Asia but the streets of Chicago. Many fellow students, finishing up their summers at home before returning to Penn, reported watching Chicago with their weeping parents, many of whom had lived through World War II and wondered if the freedoms they’d fought for were fraying.

34th Street was born into this churning zeitgeist as a weekly supplement to The Daily Pennsylvanian in October ’68. We started 34th Street to provide an expanded home for arts coverage and breathing space for the stylish, sprawling, personal long–form New Journalism pioneered by Tom Wolfe and Hunter S. Thompson. Beyond offering glorious open pages for text, art, and photography, 34th Street, crucially, provided a locus for a new campus community being born.

In 1968 there was no Internet, social media, email, underground or FM radio, or even more than a few alternative print weeklies. The establishment media—newspapers, TV, radio—were still living in the Mad Men ’50s. The white, male, government/business establishment power structure, long unquestioned and unchallenged, monopolized dissemination of news—“There were 50 people at the antiwar rally, according to police,” lied Philadelphia’s newspapers and radio stations, when there were more like 5,000. There was no media home for alternative, progressive voices, thoughts, insights, points of view…the truth.

The Daily Pennsylvanian provided one counter–establishment outlet—we were thrilled when Penn’s president, Gaylord Harnwell, referred to The DP as “the daily tissue of lies.” But The DP was locked into the tight, limited format of a newspaper. The news needed room to breathe.

•

We created 34th Street as a greenfield, with no preconceptions, no limits, no traditions (and of course no budget). Given the boiling social tensions of assassinations, police rioting, and the fundamental questioning of all Authority for the first time in generations, one might have expected 34th Street to begin life squalling with anger. But the editors, mature and battle–weary college juniors that we were, had already seen enough anger. We aimed to give readers and creators not only a new home for emerging perspectives and art forms, but also useful gifts of knowledge about Penn and the surrounding world. So we decided to counter–program.

Bill Mandel's Letter from the Editor, from the October 11, 1968 issue of Street.

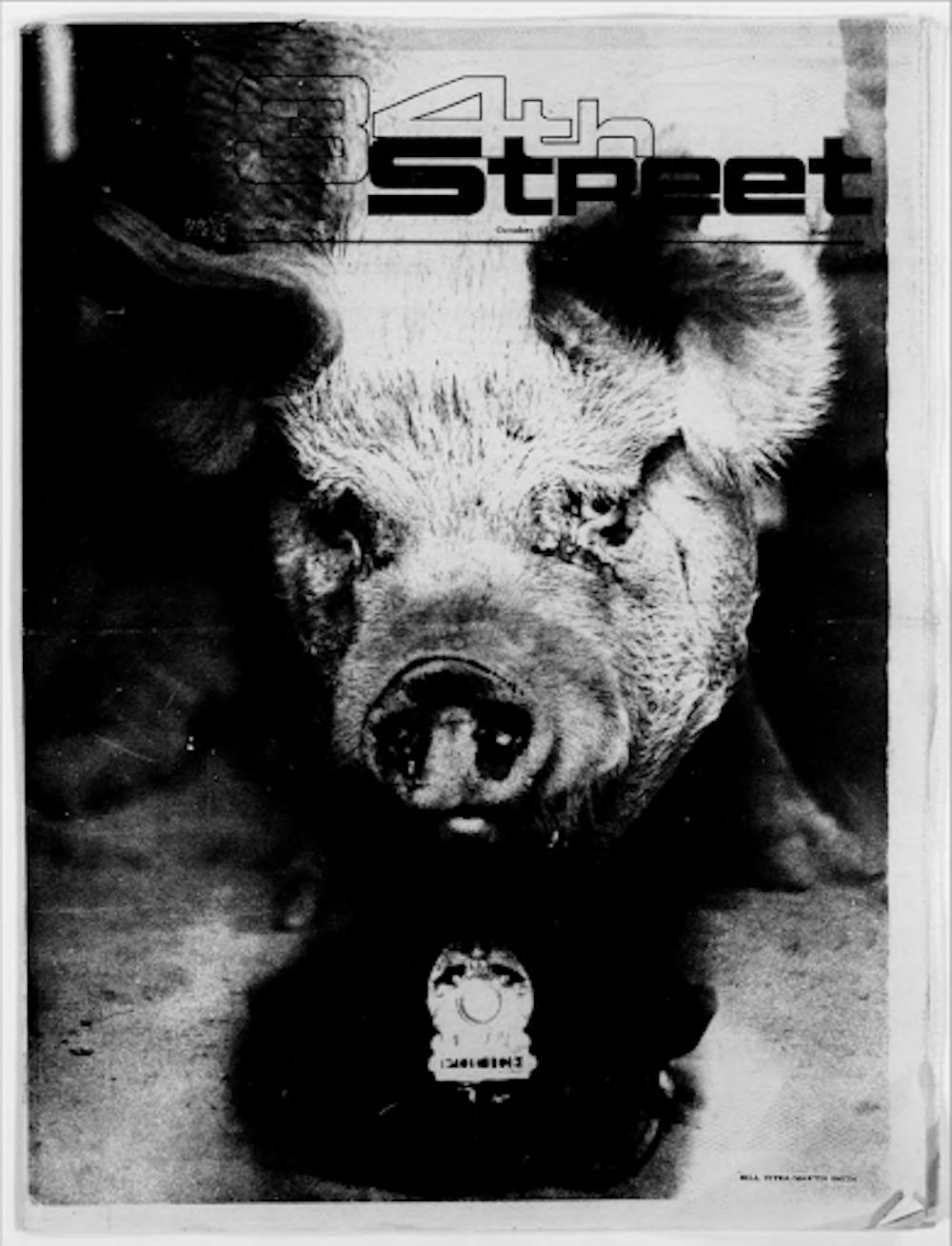

Our very first issue, in October ’68, carried a cover story called “RFD” (Rural Free Delivery) that argued all wisdom did not reside exclusively in the coastal elites (sound familiar?). Our second cover story, “Don’t Oink Back,” addressed aggressive police behavior by advising students to stop calling police officers “pigs” without 1) thought to the humanity behind the shield, and 2) realizing that meeting brutal behavior with brutal name–calling merely confirmed the Establishment’s worst criticisms of university spoiled brats.

Sure, the politics were serious, but we were also having fun. For the “Don’t Oink Back” cover, we needed a photo of a mean–looking pig wearing a police hat. Pre–digital editing software, if you needed a photo of a pig wearing a police hat, you had to find a pig and put the hat on it.

The fearless photographer Martin Smith (W ’69) was willing, so we trekked out to the University’s veterinary farm in Kennett Square, where we quickly realized that real pigs are big (400+ pounds), ornery, and averse to posing. We waded through pig slop to one relatively benign–looking swine. Our safety margin allowed time for one take, one shot. Summoning Frisbee skills and a prayer, I lofted the police cap toward the pig. For just a moment, the cap sat just right. Martin brilliantly captured it, and we fled flailing and flopping through the muddy offal. And as it turned out there’d been little to fear: the pig didn’t chase us. It just ate the hat. On the ride back to West Philly, Martin’s Nikon was the only thing in the car not covered with pig excrement. But we were happy. We had our cover.

•

Though I was the founding editor, 34th Street was the idea of Charles (Chuck) Krause (C ’69) Editor–in–Chief of The DP from 1968 to 1969. During his editorship, Charles brought a unique sense of artistry and experimentation to The Daily Pennsylvanian, at one point turning the paper into a single–sheet wall poster that was slapped on plywood sheets like giant concert flyers to be read by students boycotting classes and occupying campus buildings to protest the war. In the half–century since, Charles has continued using the powerful journalism inherent in fine art to influence social and political change. After a career as a foreign correspondent for The Washington Post, CBS News, and PBS (as well as serving as a Penn Trustee), in 2011 Charles opened the Reporting Fine Art gallery in Washington, dedicated exclusively to showing modern and contemporary politically–engaged art.

•

I started this piece recalling September ’65’s omnipresence of “Satisfaction” echoing across the freshman Quad, and the did–that–really–happen sight of frat boys beating up Vietnam war protesters in front of College Hall. Another sharp memory of that autumn was Homecoming, where we watched the 50–year Class of 1915 march (totter and shuffle stiffly, it seemed to us) proudly by. These white–haired, shriveled relics were veterans/survivors of World War I! I couldn’t imagine a time so ancient, or a consciousness so removed from the surging issues preoccupying us in 1965.

Now I’m part of the cohort that, if we live, will toddle along under our 50–year banner at Homecoming 2019. Will we look equally prehistoric to the freshman Class of 2023? Probably. But 50 years can teach a lot. I understand now that the Class of 1915, under its wrinkles, had not only accumulated wisdom beyond my immature understanding, but had remained intellectually passionate and engaged—perhaps more so then than ever—as their bodies developed the halting gaits and facial wrinkles I’d ignorantly dismissed as markers of irrelevance.

All of which is to say that starting 34th Street remains one of the greatest thrills of the founders’ lives—regardless of what we accomplished later—and the fact that Street still exists a half–century on is a proud testament to an unbroken Penn tradition of curiosity, inquiry, dashes of snark & cheek, and the compulsion to make sense—in words and images—of whatever world we find ourselves in, so we can make it a better place.

Bill Mandel is a seven–time Pulitzer Prize nominee—no cigar—for columns (blog posts before their time) in The San Francisco Chronicle & Examiner. Bill left daily journalism in 1994 when he saw the Internet would kill newspapers as we knew them, and has worked since then helping Silicon Valley executives shape their communications to address issues in the industry and the larger society.