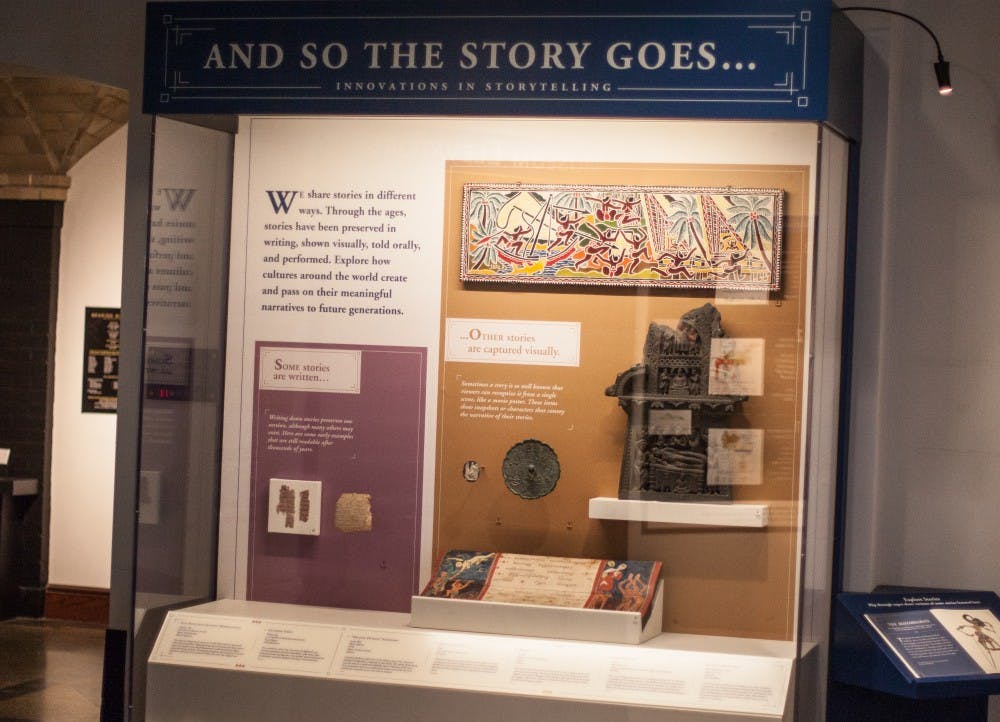

Through March 17 of next year, three Penn students, Braden Cordivari (C ‘18), Fiona Jensen–Hitch (C ‘19), and former Street writer Linda Lin (C ‘18) will have their own curated exhibit displayed in the Penn Museum. Titled “And So the Story Goes… Innovations in Storytelling,” the public exhibition explores how different cultures take on communicating narratives and innovated storytelling.

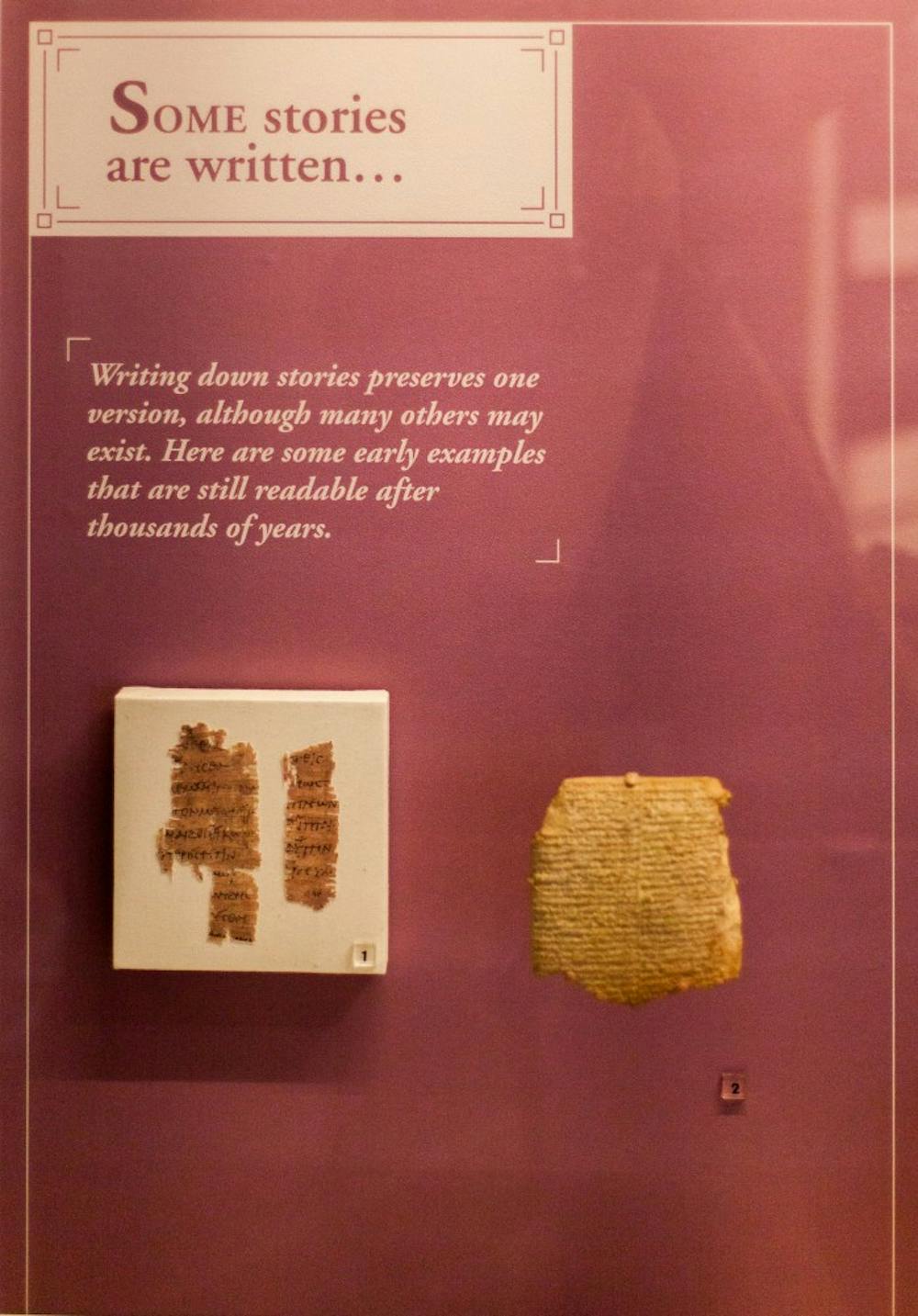

The exhibit consists of a wide–ranging set of artifacts from the Museum’s international collection that represent various, unique traditions of storytelling: a cuneiform tablet from Iraq with the tale of Gilgamesh written in Sumerian, a 1970s storyboard featuring a Caroline Islands story, and a Neoclassical gem carved with characters from Iliad. There’s a Burmese mask, a Japanese shadow puppet, a Thai Buddhist manuscript, and a Cochiti Pueblo clay doll.

The opportunity to curate an entire exhibit emerged through the Museum’s Student Exhibition Internship Program, a year–long position in which student–curators develop an exhibition in line with the Provost’s yearly theme. The theme of this past year? The Year of Innovation.

From developing content to creating the text for labels to designing the installations, Cordivari, Jensen–Hitch, and Lin oversaw the entire process. Originally, the topic they were assigned to within the larger theme of “innovation” was on the practice of writing, including the materiality, what people write on, and types of writing, such as creative writing, intellectual writing, and op–ed.

But “writing wasn’t necessarily the way that we want the objects to be solely perceived as, and it is not as dynamic to us,” Fiona explained. “So we shifted from writing to a broader theme of storytelling, which is a more common human aspect. Hopefully storytelling can connect to visitors, probably even in ways that they haven’t thought of before.”

As the three looked into the objects, they ended up grouping all 15 objects into five sub–thematic sections: written stories, visual stories, stories told by storytellers, stories told in performances, and stories told using aids or tools. This shows how people have used objects to change the ways that stories are told, depicted, and embodied.

One of the displays is a Navajo string game. The thin strings stretched out to form images of scenes and objects are not merely, as it is described, a game, but a tool for story narration. It tells of the shapes of constellations in narration, as the bands reshape to form the stars of the Coyote constellation tossing the stars into the sky. While this is not at once clear, a video recording provided by the Navajo Nation Museum is shown alongside the string game to recreate how the string was used. Such interactives are particularly important as many of the objects are used in performances or as props in telling stories, the full effect of which would be lost without seeing them in use.

The string game is only one example of storytelling. But the act in itself is all but universal. Some begin as oral tales; some, as written texts; others, as elaborate performances. For example, the exhibit also includes a 3rd century Egyptian papyrus fragment, a Neoclassical gem from Europe, and a sung reconstruction of the Greek epic, all depicting aspects of the story of Homer’s Iliad. Whether on papyrus, gemstone or through computerized technology, the same narrative is shared across time persists, albeit through different means.

“You cannot universalize things. We are careful that we didn’t make it teleological or make it like a timeline. Because it’s cross cultural and context specific, we can’t say this form evolved from that or was transformed from that,” Fiona explained. “The aspect of innovation was simply the method of storytelling. We want to show the modes that you didn’t think about before.”

Similarly, many objects are not tied to just one type of narrative. The Japanese horagai conch–shell trumpet in the exhibit, for example, had been used by militaries, Buddhist monks, and street performers. The Javanese puppet on display was also selected as an example of how a written story came to serve as a rich source of artistic and cultural inspiration, and is still told in a myriad of ways, including shadow puppet shows. “Story is a mechanism of collective memory. It’s up to storytellers how they want to pass on a story, whether they want to change the narrative modes or add in their interpretations,” Fiona commented.

“And So Story Goes” illustrates how storytelling itself is a means of human creativity; it doesn’t need to be an improved version of a previous form or have a technological advance to be considered as innovative.

And so the story goes.