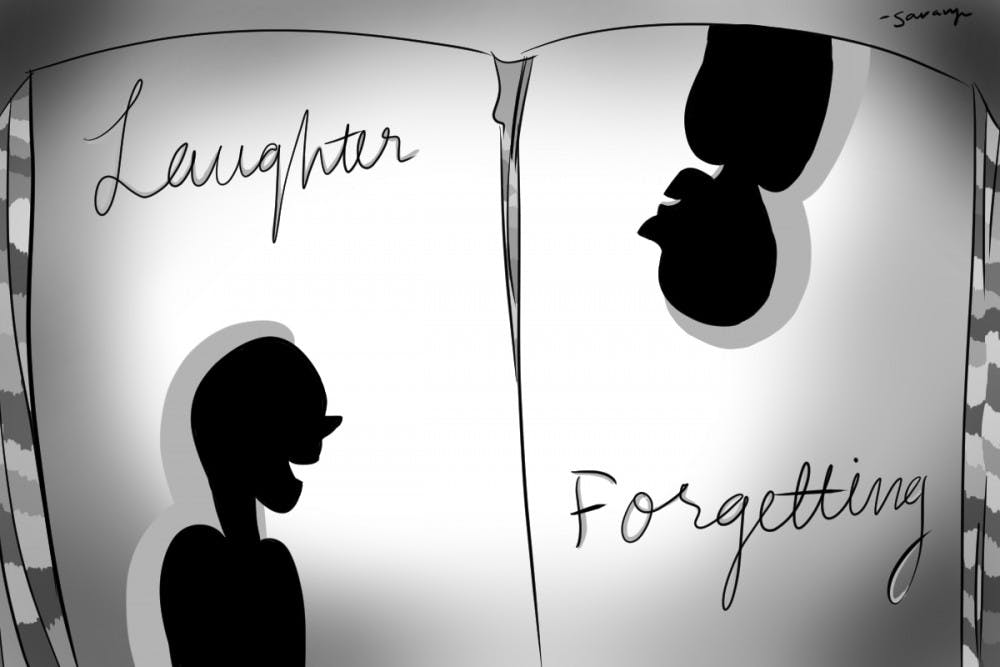

The book ends with a line about bare genitals. To be specific, bare genitals staring stupidly and sadly at the yellow sand. And no, that’s not why this book is fitting to read after NSO. The ending of Kundera’s The Book of Laughter and Forgetting is a showcase of the line between the meaningful and the meaningless, a line crossed by laughing and forgetting. And that’s why this book is fitting for the new year—past the literal level, past the political jest, and past the tinges of nihilism is a reminder to laugh and to forget, to draw our own lines between what is meaningful and what is meaningless.

This week is a new start: it’s excitement and it’s nerves. It’s joy and it’s stress. And too often lost among all these mixed emotions is the sight of what really matters at the end of the day. That line is blurry. In his novel, composed of seven isolated narratives strung together by their underlying themes, Kundera presents laughing and forgetting as an antidote. Laugh at the past, laugh at the mistakes. Forget the wrongs, forget the disruptions. To move forward, the past shouldn’t be given any more weight than what the future holds. It’s a message synonymous with “Just keep swimming” or “Don’t look back.”

But at the same time, while laughing and forgetting can be a solution, it can also be a force of destruction. In the first few pages, Kundera recounts a photograph from 1948 set in communist Czechoslovakia with Vladimir Clementis standing next to Klement Gottwald, the first president of the state. When Clementis is charged with treason two years later, his image is removed and his fur hat once sitting on his head is no longer his, but Gottwald’s. The message is clearly political and societal, but the same applies to the individual. Laugh at the past, laugh at the mistakes—and erase ourselves. Forget the wrongs, forget the disruptions—and erase our personal histories. As Kundera puts it, laughter originated with Satan, but was learned by angels, making it such that it’s impossible to truly know if it is angelic or demonic. It is then the balance of the two extremes that allows us to draw the line between the absurd and the meaningful and make sense of what it is that carries significance for us.

Yet even with all the intricate, underlying political and individual implications, Kundera’s words flow easily. Each of the seven parts contains some drop of inane that makes the book a good read even if just for an amusing story. Take what you will of it—The Book of Laughter and Forgetting is one for a laugh, for a historical view, and for a personal reminder. And that’s why this is one to read for the start of the new year.