Years ago all of the shelves in Penn’s Barnes and Noble store were consistently filled to the brim with books—spines out. Now, employees stack the shelves with the covers out to make the shelves look less empty. If one book is bought, employees will come back later and shuffle the books into a more appealing configuration. Only a handful of books span each shelf in the Art History & Criticism section. In Photography, one shelf has only four books on it. Two shelves in U.S. Travel don't have any books at all.

One employee of four years has watched as the store's book section slowly bled out, its shelves gradually replaced by coat racks of university apparel.

"Every year we send back so many boxes of unsold books,” he said matter–of–factly from behind the Information Desk.

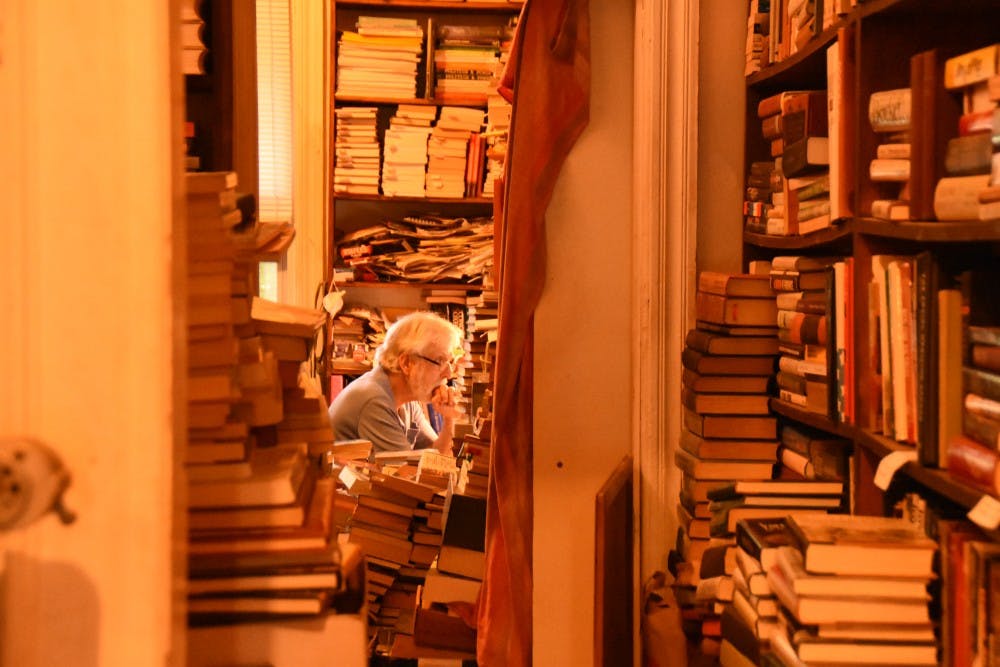

Debbie Sanford (C ‘71), the co–owner of House of Our Own bookstore on 39th and Spruce Streets, started the store in the fall of 1971 as an intellectual escape from the trauma of the Vietnam War and the looming perils of the draft. The store grew to house an arts and crafts section, course books for students, and every other imaginable literary genre. “Prior to e–mail, professors always came in to place their orders for the upcoming semester,” Sanford recalled. “We would go around the store and talk about what books they have been using and what worked. We really enjoyed it. We loved doing it.”

Since the internet became mainstream in the late 90s, book publishers and stores have come to rely on the it for sales. “The world has changed,” emphasizes Greg Schirm, the other co–owner.

Now, Amazon accounts for more than half of all online sales, placing small businesses in a stranglehold. To even allow book publishers to sell on their online marketplace, Amazon demands steeper discounts, more prolonged periods to pay, and better shipping. The company's approach to publishers was once called "The Gazelle Project" after Jeff Bezos, Amazon's founder and CEO, said that the company “should approach these small publishers the way a cheetah would pursue a sickly gazelle.”

DP File Photo

In the face of such strong–arm tactics, bookstores around the country—including those that orbit Penn's campus—have had to drastically reevaluate their businesses. The opening of the physical Amazon@Penn Center—the only one in the entire city—blocks away from their stores, further compounds the threat.

"Did the Amazon Center coming to Penn have an impact on our business? Yes, yes it did," Ashley Montague, the owner of the Penn Book Center, said with a sigh. "It moved us from being basically in a good position to being in a not good position."

For Montague, that meant stepping away from their highest source of revenue: textbooks.

"We had seen some declines because of Amazon, but once the depot came to Penn it went to 20%," she said. "That was when we said 'Oh, O.K. We can't be bringing in massive quantities of books, employing large numbers of people to manage these books, and simply pack up the books and return them because of the Amazon phenomenon.'"

It isn’t the first time that booksellers have had to reassess their business—the mass–dissemination of the World Wide Web and the e–reader soon after proved to be formidable hurdles for the industry as a whole. But Amazon is different. For many small businesses, the company isn’t just a hurdle, or a setback, but an existential threat. It forces stores to not only diagnose what is economically viable but to also look inward and to consider what being a bookstore fundamentally means.

Montague's strategy now, as it has become with many stores, is to become everything that Amazon is not. That means not competing on price or delivery time, but doubling down on trade books and the idea that those who shop at independent bookstores, at their core, are those who want to get a book recommendation for another person, who love to aimlessly comb through the shelves in search of literary gems, who join book clubs.

This emphasis on community–oriented bookselling has resulted in hiring the store's first event organizer—a graduate student by the name of Erik Baranek. Baranek is neither a social media guru nor a public relations specialist, but instead a regular bookworm and an ardent defender of the independent bookstore.

Ashley Montague, Penn Book Center

"There are things that Amazon can never beat a brick–and–mortar store in. They can have the most complex algorithms to tell you what books you are going to like because of what you ordered in the past, and they might even be right most of the time, but it's a really different experience than getting a recommendation from a person," he said. "As for why I was brought on, I think is for people to start having those experiences and that they like those experiences."

It’s a sentiment that Sanford and Schirm from House of Our Own echoed: “Some people now, which never happened in the past, come in an ask, ‘I am looking for something to read, what would you recommend?’ said Schirm. “That never happened in the past."

Penn's negotiations with Amazon started in 2014. Before then, several Amazon centers had already existed on college campuses across the country. But unlike the other universities, according to Christopher Bradie, the Associate Vice President for Business Services and overseer of Penn's relationship with Amazon, Penn did not want a physical retail extension of the Amazon’s online shopping experience. It was looking to mitigate the influx of packages coming to campus. According to Bradie, campus package rooms in dormitories were buckling under the weight of a massive flow of Amazon deliveries, while at the same time, packages being sent to students in off–campus housing were being stolen. To Penn, the center would be a solution these problems.

While both the Penn Book Center and employees at Barnes & Noble were eager to point the finger at the Amazon@Penn center for all of their woes, Penn Business Services contends that the problems these companies were facing would have persisted with, or without, the center.

The center has brought additional benefits that have made its services more and more appealing to student shoppers. New Amazon Student Members get Prime membership benefits for free for the first six months—and then eligibility to receive further discounts on Amazon Prime till graduation. Not to mention that if one were to order a Prime–listed item before 10 am, the item would be ready to pick up at the center the next day for free. To promote these benefits, the company has even hired “Prime Student Ambassadors” on college campuses to hold informational events and giveaways where they coax students with free phone wallets and sunglasses in order to sign–up.

According to Julia Wietrzychowski, a Wharton junior and a Prime Student Ambassador on Penn’s campus, her target demographic is incoming freshmen: “A lot of people when they are going from high school to college they wouldn’t necessarily have their own Prime account… so it’s about spreading the word that the first six months are free,” she said. “One of the frames that they want us to go at is that if you need something in a pinch it’ll be there the day of.”

The company currently has over 100 million paid subscribers, with a retention rate of over 90 percent, according to Bloomberg. That’s higher than CostCo, who've long touted their loyal consumers.

Both corporate Amazon and Amazon@Penn’s manager did not respond for comment.

The question that remains to be answered is whether or not small retailers and Amazon can exist side–by–side within the bounds of University City in the long term.

For Ed Datz, the Executive Director of Penn’s Facilities and Real Estate, the Penn department that oversees the small retailers that operate out of Penn, that answer is yes. He’s confident that small brick and mortar businesses will continue to thrive on Penn’s campus:

“If you go ahead and look at it five years ago, with the proliferation of tablets and e–readers, there was a belief that bookstores were going to go ahead and fade away,” said Ed Datz, “But what you have seen is no different for vinyl coming back to records, and people returning to reading from an actual book.”

Greg Schrim, House of Our Own

Part of what will contribute to the success of that coexistence is the university’s new “Shop Penn” marketing initiative. Announced in May of 2018, the marketing campaign is aimed at reinvigorating retail—both big and small—that operate out of Penn–owned real estate. While the Amazon@Penn center is part of this campaign, small bookstores like House of Own Own and the Penn Book Center have the most to gain because they are now able to get marketing that they never had before.

For Barbara E. Kahn, a professor of marketing at the Wharton School of Business and the author of the recently released book “The Shopping Revolution,” loyalty is what has made Amazon such a disruptive force—for all retail, not just books—and in order for small retailers to continue to stay afloat they need to adapt to the retail game that Amazon is no doubt the master of.

“What used to work doesn't work anymore," she explained. “If you are going to compete on easy–to–deliver and cheap price, you won’t win against Amazon.”

James Meadows is a senior from Washington, D.C. majoring in Communication. He is the Crime and Legal beat for the Daily Pennsylvanian.