At the end of our last legal studies class this semester, the professor, in his characteristic hyper–excited tone, was shouting instructions for the final paper: “don’t use flowery language,” “get to the point,” “keep it short and relevant, not sweet!”

Fairly sound points, I thought, albeit slightly contradictory since he was running overtime. Arguably the most memorable was “write like Antonin Scalia.”

Perhaps one of the most entertaining parts of RBG, Julie Cohen and Betsy West’s newest documentary, is the brief insight into “the odd couple:” Justice Ginsburg and Justice Scalia. Ginsburg is shy and reserved, Scalia was flashy and effusive. Ginsburg seeks to use the Constitution to “strive for a more perfect union,” Scalia wanted to find out what the words “meant to the people who ratified the Bill of Rights, as opposed to what people today would like.” Ginsburg’s discourse is notoriously liberal; Scalia’s skewed particularly conservative. And yet, they worked well together, and not only thanks to their mutual love of opera.

As Ginsburg recalls, her mother, who is afforded considerable screen time, gave her two pieces of advice. One was “be independent.” the other was “be a lady—don’t allow yourself to be overcome by useless emotions, like anger.” And Ginsburg, carrying herself with grace and elegance at all times, regardless of how garish her surroundings were, follows that advice religiously.

Ginsburg’s career echoes her thoughts on opera, which she articulates in one of the interviews: “The sound of the human voice…it’s like an electric current.” She rose to power during a time when freedom of speech was jeopardized by the Red Scare looming over American political thought, and eventually became one of the loudest, fiercest voices advocating for gender equality, completely revamping both the legal profession and the approaches to court rulings to make them more inclusive.

Notable about RBG is the fact that, in the relatively brief ninety–minute running time, it manages to move away from Ginsburg’s otherwise steely demeanor and examine her relationship with her mother, husband, grandchildren, and even personal trainer.

Wearing a blue sweatshirt with the words “Super Diva!” emblazoned in big, white letters on the front, Ginsburg, aged eighty–five, lifts, does twenty push–ups a day, and when she’s done, she’s ready to go again. Her determination is, as she says, both what accounted for her impressive career and what made her husband fall in love with her: “He was the first boy I ever knew who cared that I had a brain.”

Ginsburg herself thinks that without Martin, her husband, she would have been “perhaps 22nd on a list [of prospective Supreme Court Justices], not first.” Both fans of one–liners—Ruth, of burns, or “Ginsberns,” Martin, of silly, but never inappropriate remarks—the couple is shown as a source of inspiration for young men and women. RBG uses their marraige to illustrate how a relationship based on trust and mutual respect can go beyond apparent differences and give way to fruitful lives and careers. The two directors put great effort in portraying the marriage as Ginsburg wanted: case briefs and striking quotes are intercut with home–videos and love letters from Ginsburg’s personal archive, and the result is as much a love story as it is a documentary.

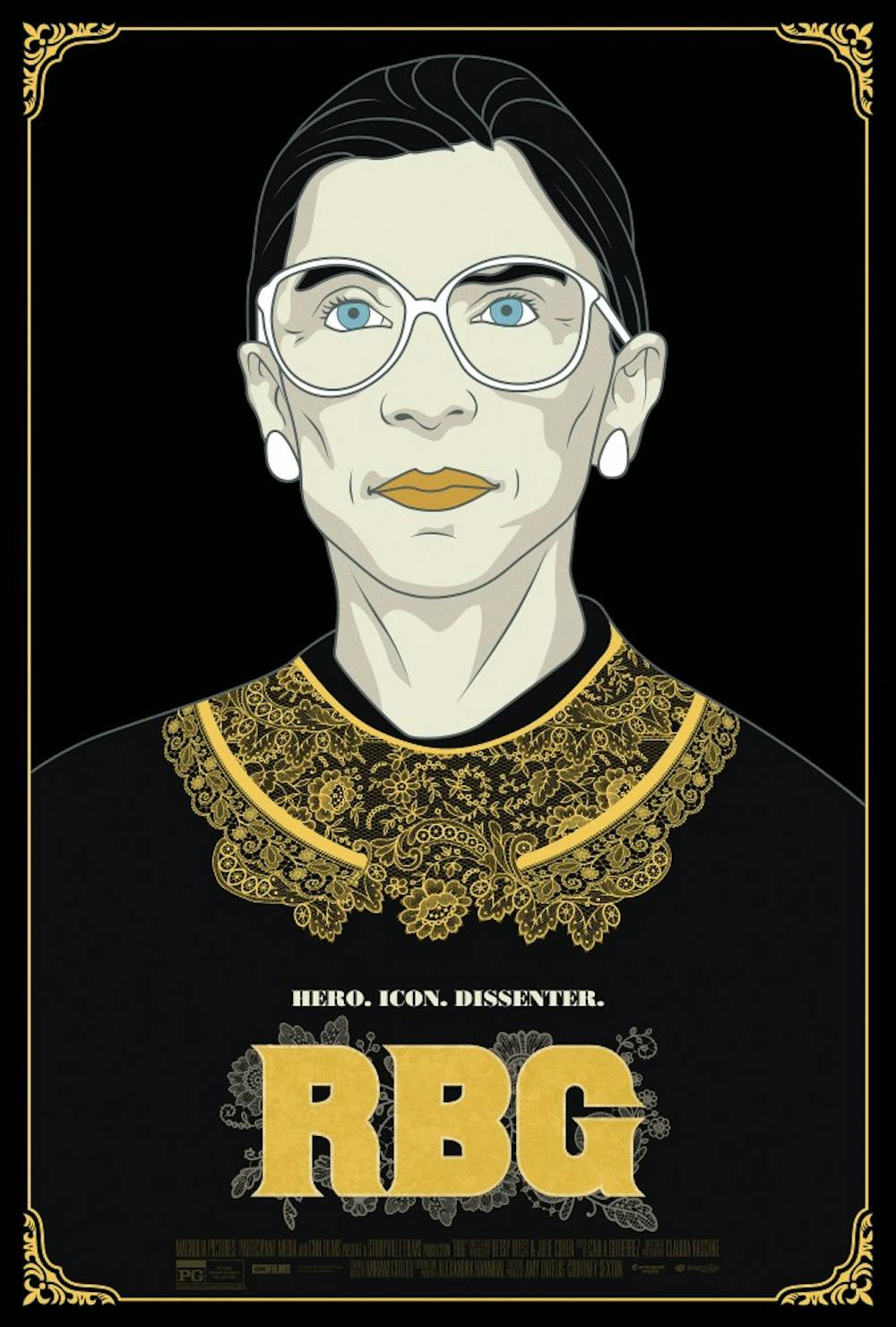

RBG, though barely noteworthy production–wise, will undoubtedly strike a chord with liberal audiences, for whom it is obviously intended. But the sheer force of Ginsburg’s speech and her remarkable achievements—she is, as one of the interviewees puts it, “the closest thing to a superhero [she knows]”—is what makes the documentary worth watching regardless of political affiliation. If anything, it is accessible archival material on a character whose life, both personal and public, is as striking as her characteristic statement, with which she continues to strike down any conservative opinion: “I dissent.”

Rating: 3/5

‘RBG’ opens May 11th at the Ritz Five.