When I was little, I would reread the Harry Potter series over and over again, its words conjuring images of the epic battles between Harry and Voldemort. But ever since the film adaptations appeared on HBO, I found myself curling up with my favorite characters in a different medium. Maybe it’s because watching it on TV is more passive. There’s no flipping of pages or scanning the lines; my eyes would fix on the same screen over the two hours. Or maybe it’s because having Harry on screen meant that I didn’t have to lug the heavy book–boxed set around in my backpack. Regardless, the outcome has been that I’ve read and seen the Sorcerer’s Stone countless times, leaving me looking for other ways to revisit my favorite characters. This semester, my screenwriting class provided an answer: read the screenplays.

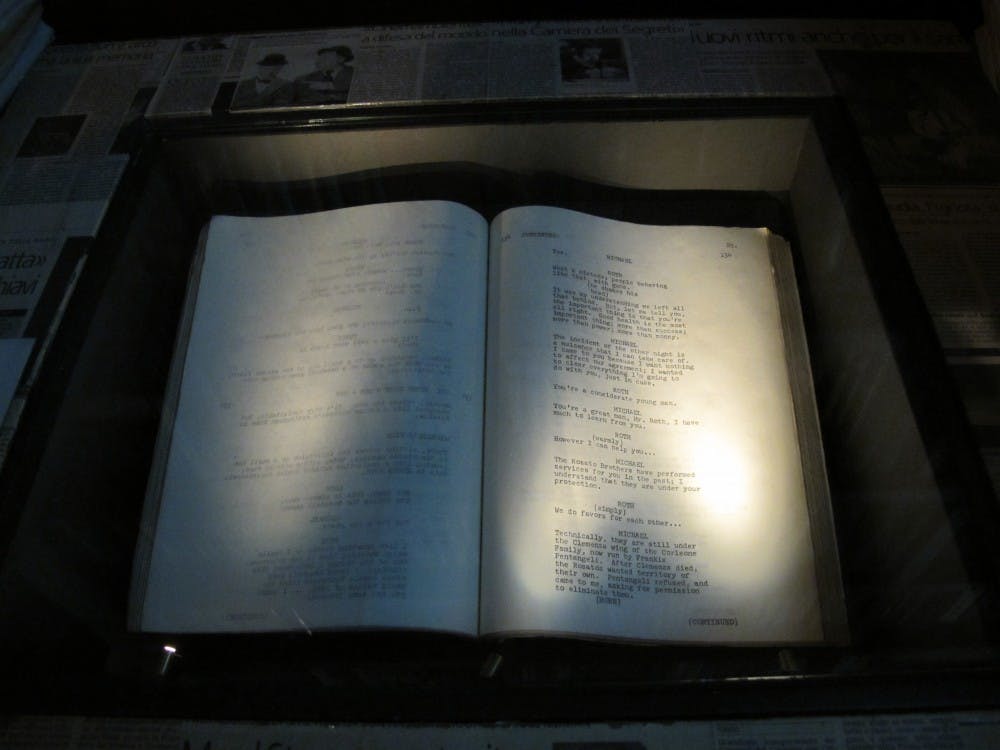

For those unfamiliar with what exactly constitutes a screenplay, it’s the script of a movie—the lines, the acting instructions, the scene directions, everything. Go stage left. Gasp in horror. It provides all the familiarity of the plot, but with a different form and from a different point of view. With a good screenplay, like a good novel, the action unfolds in front of the reader, the characters standing right above the pages. But unlike simple viewership and television–watching, screenplays require the reader to take an active role. In my own experience, I’ve become more attuned to the screenwriter’s voice, plot points, and divergences consequent of parting from its original source material or adding more information into the final film. By reading screenplays, I’ve learned what make my favorite films my favorite films.

The typical structure of the screenplay is as follows: three acts containing the background information, the confrontation and climax, and the resolution. Such a structure is to film as the golden ratio is to painting. With the first act, the screenwriter presents the setup, the inciting incident, and the first plot point, which typically falls around the 20–25% mark of the screenplay. The second act consists of the confrontation and the climax of the novel, when the protagonists attempt to solve the problem initiated by the first plot point, but fail to do so. This is where characters develop, either in isolation or with their cast of mentors and allies. Finally, there’s the third act: the resolution. The problems are solved and the questions answered. At times, the end of the films evoke the opening but are juxtaposed to show the aforementioned character growth. Even the most groundbreaking films, such as “Toy Story,” “Thelma and Louise,” and “Star Wars” adhere to this very structure.

The act of reading screenplays has also turned some of my least favorite films into my favorite pieces of writing. “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” is the best example. For those of you haven’t seen it (go watch it; it’s on Netflix), the plot follows Joel, who had literally erased the memory of his girlfriend Clementine after a fight through a New York City firm. Though often lauded as one of the best movies of all time, the movie felt slow to me and the supporting characters flat. It was hard to believe that Kate Winslet (once a stunning 1920s heiress) would fall in love with SNL’s oddball Jim Carrey. On the page, however, I discovered that these issues were resolved and the story was actually infused with unforeseen and unfilled plot twists and character developments. The final discovery infused the script with more cynicism. It’s impossible to delve into this without spoilers, but the lesson was clear.

Screenplays are different than movies and books. They often hold separate stories that contain more literary nuance than a blockbuster can carry. Because of this, even though it seems as if watching may feel easier, I’ve returned to a new way of reading.