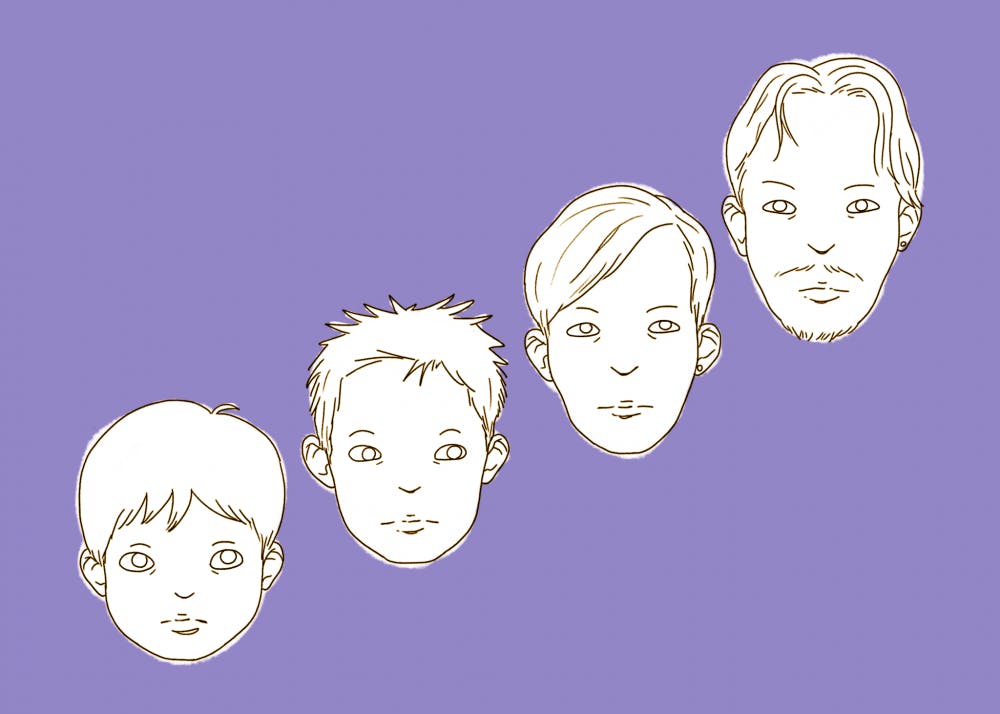

There were a lot of things to like about Boyhood. It was sweet and thoughtful, like any good coming–of–age tale should be, and, perhaps more importantly, it felt like a fully realized vision. The director, Richard Linklater, was on a mission in making this film, as he sought to do the unprecedented and use the same young actor again and again over the course of 12 years, to the effect that the audience could see a boy grow into a man right before their eyes. This unconventional approach produced a kind of raw movie magic—it was something people had never seen before. It is easy to attack the film for being nothing special, given how ubiquitous the slice–of–life coming of age film is. I dare to disagree.

Unconventional filmmaking can feel gimmicky, particularly in American cinema, where movies tend to be fairly cookie–cutter. Boyhood fits most of the criteria for solid coming–of–age drama, with one notable exception: the fact that it was a 12–year undertaking. This singular, but significant difference in the director’s vision opens up a new space for experiencing a story. It's difficult to deny that watching a character grow up before your eyes makes the movie feel more real, makes the characters feel closer to you, and their lives, however ordinary, mean more to you. Boyhood transcends its gimmick. It is a flawed film, as every film is, but that's no reason to reduce it to the brilliant idea and execution of that idea that got it so much critical acclaim in the first place.

In the end, it all comes down to the director’s vision, and what an unconventional approach does to elevate that vision. One particularly striking example is Sean Baker’s 2015 comedy Tangerine. There is a lot to unpack with this film when it comes to unconventionality—including the casting, filming, and subject matter. Tangerine offers a glimpse into the lives of people living on the margins of society, who we often neglect, but does so in a heartfelt and oftentimes hilarious way. The two main characters are trans women making a living as sex workers in Hollywood. The actresses who portray these women were cast in spite of never having acted before. Everything about the film, including the dialogue, feels raw and honest. This is enhanced by the use of three iPhones to film the entire movie.

Tangerine is important for much more than being a feature–length film taped entirely on smartphones, but the rawness that comes from the familiar grain of the iPhone camera does wonders for the mood of the film. It helps bridge the gap between the humor and grim reality that weave in and out of the movie. The humorous moments are filmed in a way we associate with online videos and hidden cameras, whereas the serious ones are dark and gritty. Baker, like Linklater, had a vision of how a unique take on production could alter and enhance the story being told. He too transcends the gimmick, and in doing so produces a moving portrait of women living at the margin who we rarely give a second thought.

A good movie that uses unconventional filmmaking techniques should stand for something. That special something should elevate a high–quality film and engaging story to new heights. In Boyhood, the 12-year production schedule reimagined the coming-of-age genre. It enhanced the effect of the ordinary motions of growing up and made them palpable. Similarly, by filming Tangerine on iPhones, Baker amplified a story full of raw intensity and grit. When a film gets buzz for attempting a feat of production, that doesn’t necessarily mean it is lacking in another department. Instead, projecting the themes of the film beyond its content and into the way it was made creates a unique viewing experience worthy of our consideration as people who love the craft of film.