When Zoolander 2 was released in 2016, I did everything in my power to pretend it didn’t exist. I immediately dismissed every trailer and subway station ad that inevitably found a way to sneak into my life, as though they were figments of my imagination. There was no way, I assumed, that the buffoonery that made the 2001 film Zoolander so outlandishly funny could be replicated without feeling completely worn out. I was also concerned that revisiting some of the original gags would force me to accept how juvenile they always were. Thankfully, I was able to avoid Zoolander 2 until it completely fell off the cultural radar.

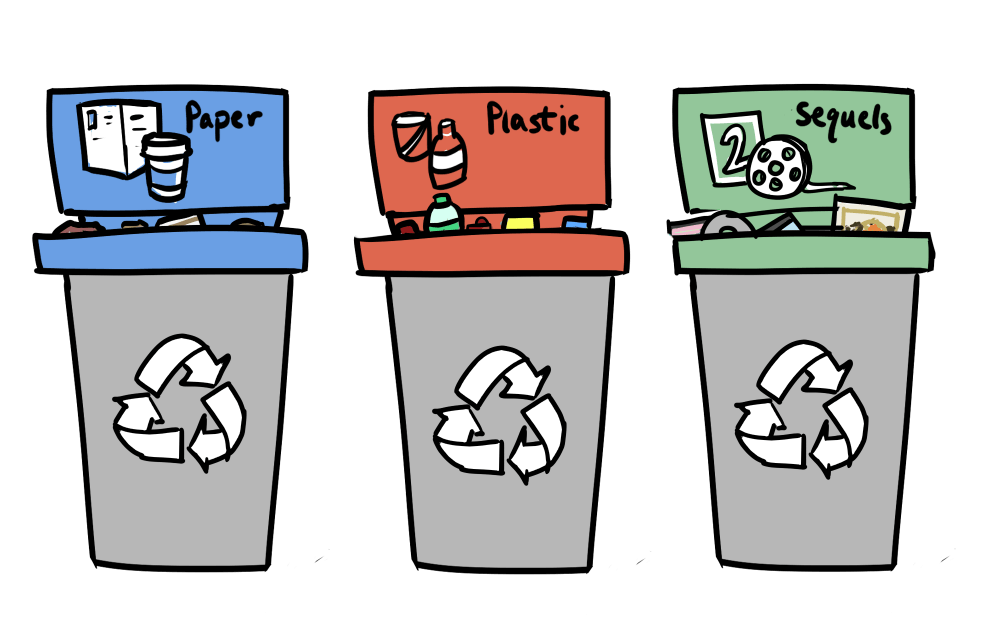

My fear was based on the general understanding that most sequels are made almost entirely for commercial reasons, and don’t need to be all that good to cash in at the box office. Although Zoolander isn’t a traditionally “good” film whose sequel would be expected to diminish in quality as a result of being a purely commercial venture, it does have the kind of stupid humor that shouldn’t be revisited beyond the original cult classic. When a movie delivers something to audiences so appealing that a sequel seems in order, revisiting those successful cinematic elements can backfire dramatically.

A phenomenal example of this is the 2017 film Kingsman: The Golden Circle, which received significantly less critical favor than 2014’s Kingsman: The Secret Service. Cartoonish violence and a ridiculous villain were what made the original film stand out. Too much cartoonish violence and an obnoxiously ridiculous villain made the sequel an absolute mess. Samuel L. Jackson’s comically twisted antagonist Richmond Valentine was far superior to The Golden Circle’s sadistic drug lord Poppy Adams played by Julianne Moore. An attempt to pump even more over–the–top elements into a sequel—whose predecessor succeeded by walking a fine line between passable and disasterous absurdity—demolished any chance of it elevating the original film.

Larger franchises tend to be more variable in terms of quality from film to film, depending on factors such as the choice of director and source material. Book–to–movie adaptations pose a whole new set of challenges, where the expansion of the narrative is not just a commercially valuable venture, but one that fans expect. Think of how much of a standout Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban was—every film in the hefty eight–part series (with the exception of the first) would inevitably become popular, but one shone particularly bright thanks to the wise appointment of Alfonso Cuarón as director.

Although one could name myriad cinematic classics that were let down by their sequels—Jaws by Jaws 2, Jurassic Park by Jurassic World, and The Godfather by The Godfather: Part III—the possibility of a sequel for the so–called modern LGBT classic Call Me by Your Name comes across as more of a passion project than a commercial scheme. Though the novel which the film is based on does extend into the future beyond the end of the film, the director, Luca Guadagnino, describes the possibility of a sequel as something quite unlike that literary ending.

Yet, in spite of the obvious emotional investment those involved in Call Me by Your Name put into the film and the future of its characters, the fear that too much of a good thing could ruin the subtle beauty of the original story remains. Call Me by Your Name was critically successful because it was crafted with care, and was a fully realized interpretation of the original novel. A sequel would need to somehow hit the same depth of emotion and understanding of the subtleties of human behavior as did its predecessor. Anyone who spent weeks after watching the film pondering parts of their existence they hadn’t formerly considered knows that this is not only a challenge, but a project that will likely take years of careful development. A good sequel does two things—it preserves the artistic merits of the original film and weaves them into a thematically–related, believable continuation of the narrative. Call Me by Your Name, for many audience members, was a standout in its tenderness and understanding of romantic vulnerability. The filmmakers responsible for that triumph would need to revisit those thematic elements in a new and relevant context.

In the world of big–budget cinema, sequels are relatively safe investments, as many of the top grossing films of all time are not the first in a string of films but some subsequent member of a franchise (Think Furious 7). That being said, the sequel is a fickle medium that should be handled with care, so as not to mar the triumphs of its predecessor.