The police officer told him he should have been dead.

His clothes were ripped, his eyes bruised. Beaten and shaken, Milo Garcia (C ’18) didn’t want a scolding at 3:00 a.m. on Broad Street. But that’s what happens after you fight back.

Like most Penn students, Milo had never been the victim of a serious crime. He was carefree when going out—wearing “a lot of logos,” running to Wawa, making phone calls on the street. So when three men sprang up on him and began tugging at his clothes, his instinct was to fight back.

What could have been a quick wallet or phone swipe turned into a full–blown fist fight. Though nothing was taken in the end, he wound up bruised and battered.

“It was an adrenaline rush,” Milo said. “I’m from a small town in Mexico where there is a lot of crime and that had never happened to me, so if it hadn’t happened to me in Mexico I wouldn’t think it would happen to me here.” Milo’s experience isn’t necessarily surprising—over the past 30 days, for example, there were 44 violent crimes committed in the neighborhoods making up Center City, compared to only 17 in University City. His reaction represents a larger mentality at Penn, though: Penn appears crimeless, and therefore Penn students think they are immune from crime in the wider city of Philadelphia. From NSO on, that idea of Penn’s safety is drilled into the collective undergraduate consciousness.

Despite the relative safety of campus, it isn’t necessarily the sunny utopia of Penn brochures. According to the Campus Crime Report aggregated by Penn’s Division of Public Safety, there were 28 robberies, 18 aggravated assaults, and nine burglaries on and around campus in 2016. To combat these numbers, the Division of Public Safety has constructed a system of manpower and technology—from stationed officers, real–time alerts, GPS tracking, and $3 million worth of lights sprawling the main avenues.

The University of Pennsylvania Police Department (or Penn Police) also boasts 120 officers and is the second–largest police force of any private university in the U.S.

The “Penn bubble”—that inherent sense of security on campus—popped for Milo in Center City that night when he was assaulted outside the Penn Police’s patrol zone. It was a reminder that, despite the ever–watching cameras and eyes on the street, police can’t be everywhere. When prevention fails, Penn resources can only respond after a crime occurs. Student responses after being criminalized can be complex and unpredictable, and usually invisible resources step in after the moment of danger. While the watchful eye of law enforcement may be comforting for students, others find it overbearing. In the precarious time immediately after the event of a crime, it’s often not clear what resources should be used, and depending on who you are, if you should even use them at all.

Milo still advises, though, that students use the support system that Penn has put in place. “My best advice? Use Penn’s resources,” he said. “You don’t think you need it until you do.”

Immediately after the attack, Milo had a concussion and was put on brain rest for two weeks. No class. No reading. No TV. Right before fall break, Milo found himself in midterm season without use of his laptop.

He was also angry at himself—for going out that night, for wearing his flashiest clothes, for making a phone call in an alley. Since coming back to school this semester, Milo has also started visiting the Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety at Penn Medicine, after a recommendation from SHS. The violent experience triggered Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, which Milo attributes to other previous traumatic events in his life as well. He describes it as “trust issues on steroids”—he struggles to talk to people and is easily startled, especially at night.

For student victims, Special Services offers emotional support, guidance, and counseling for any crime, according to their website. They specialize in “sensitive” crimes like rape, sexual assault, relationship abuse, harassment, and stalking. Director Patricia Brennan said they don’t care about boundaries of where the crime happened or how minor it may seem.

“Take phone theft for example. Your phone may be your lifeline. It’s not the severity of the crime, it can still shake you to the core,” Patricia said. “We know exactly how the legal system works and how to walk you through the criminal justice system to get it done.”

Milo’s case was rattling, but even close calls can dissolve a false sense of safety. Sara Ibriatta (N ’14) remembers a stressful night on Locust Walk her senior year. Returning from a long night studying in Van Pelt Library, Sara just wanted to go home to her apartment by Copa when a man began to pester her with random questions, approaching her with his hand awkwardly held in his coat pocket. Soon he was joined by a female accomplice approaching from the other direction. Sara kept backing up, telling them she didn’t have anything valuable, that she just needed to get home. They persisted, telling her not to make a scene. If it wasn’t for a group exiting Allegro and chasing the pair off, Sara doesn’t know what would have happened.

She ran home and immediately called Penn Police. She told them nothing had actually happened, but she hoped they would send out an alert warning others about the potential robbers. Yet they never did. The Department of Public Safety doesn’t send out alerts for every crime reported; just last fall, no alert went out after a man indecently exposed himself near 39th and Delancey Streets.

“Every time that someone gets robbed, someone else may have interacted with them,” Sara said. She was incredulous that the student body wasn’t warned, that someone else out there could have been victimized by the same people after she made it home safe. What she didn’t know, though, was that as soon as she called Penn Police, she set in motion multiple conversations within the infrastructure of the Department of Public Safety.

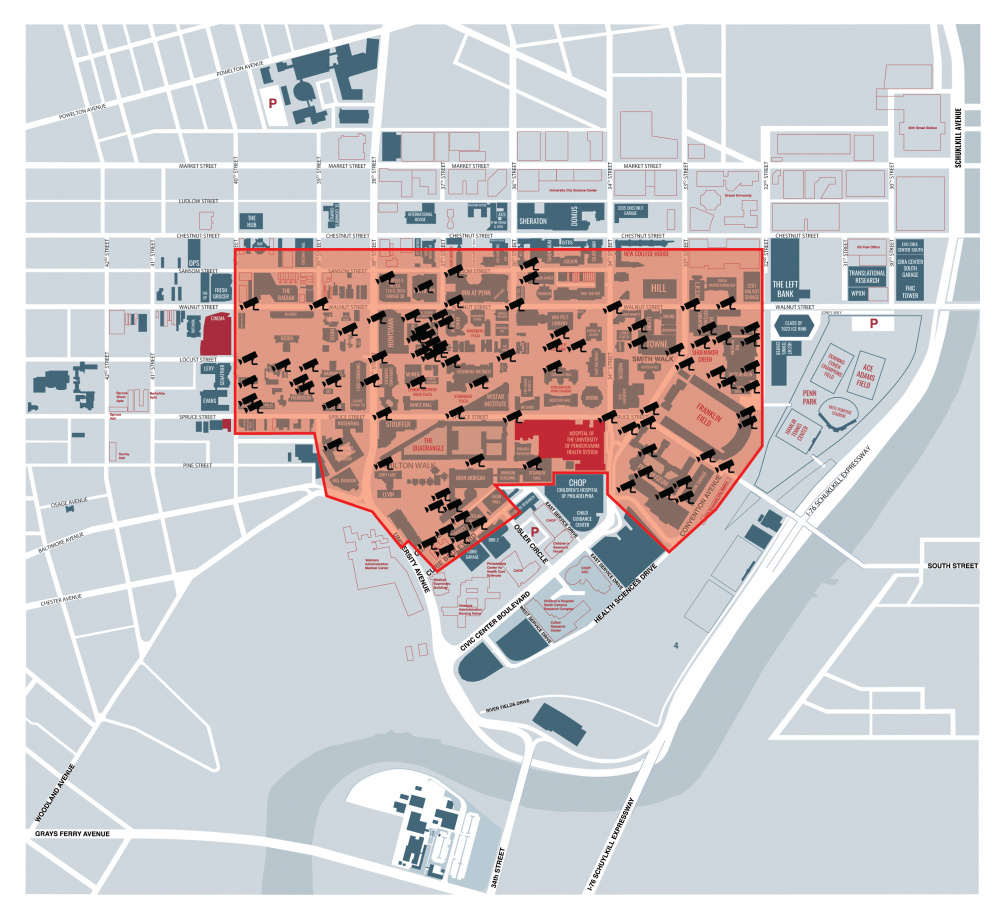

Maureen Rush, Vice President for Public Safety, said whenever a crime is reported, she and her team get on a conference call to decide whether to send out a UPennAlert. The critical question is if the crime has the potential to affect more people in the Penn community. With the patrol area stretching from 30th Street Station to 43rd Street and from Market to Baltimore, it doesn’t matter if the victims involved are Penn students or local residents. As soon as the crime is contained, a follow–up alert is sent out.

“The alerts have to be accurate, timely, and informative,” Maureen said. “We don’t want people to be alert fatigued. Hopefully, when you see that alert on your phone, you know it’s a big deal.”

The UPenn Alert system is just one way Public Safety responds to crimes across campus. Security cameras installed all around campus also allow the department to videotape crimes and find students’ exact locations. Cameras are installed in a range of locations, from the corner of 43rd Street and Baltimore Avenue, to Shoemaker Green.

Penn Police told Kiana Cruz (C ’20) that they saw her on one of their security cameras when she called them one evening in the middle of last summer.

The network of cameras is an invisible eye over Penn—usually unnoticed by students but always watching campus. It’s composed of about 145 pan–tilt–zoom cameras, which are constantly monitored, and more than 1,200 other fixed cameras.

Kiana and her friend had just gotten ice cream from Ben & Jerry’s and were walking back to 41st and Irving around 11:00 p.m. when they sensed someone was behind them. In a matter of seconds, the perpetrator snatched the wallet dangling from Kiana’s pocket and sprinted away.

“My friend’s first instinct was we should run after him, but I was like, there is no way we are ever going to catch him,” Kiana said.

Instead they called Penn Police and were told to stay put. While Kiana was still in shock, they pulled up.

“They found us in like five minutes. Detectives were there. They caught him. I made an ID. I got my wallet back. All before midnight,” Kiana said.

Kiana thought that the officers were friendly and professional, and she was impressed by how watchful they were of the situation. While driving them to the station, the two detectives cracked jokes and described stories from their days as former homicide detectives. Several months later, when Kiana had to testify in a court trial, the Department of Special Services, a division of Public Safety, drove her to court and offered support.

However, some alums like Ernest Owens (C ’14), find Penn’s security measures to be unnecessary and racially charged and aren’t comfortable seeking them out. In an op–ed for Philadelphia Magazine, Ernest said he was often stopped when returning to campus at night by Penn police officers who asked to see his Penn ID and real ID, even though he lived on campus all four years. In the beginning, he thought these were just one–time incidences. But as they happened more often to him and to his friends of color, he realized he was being racially profiled. Once, he was stopped for fitting a criminal description.

Soon he began to go out less, use Penn Rides to avoid walking at night, and wear university apparel more often to prove he was a student. The random checks decreased, to his disgust.

“I shouldn’t have had to wear Penn gear for protection,” Ernest said in an interview. “White students will be walking around at night intoxicated, and Penn Police works around them. Dark and brown students are surveilled whether we are engaging in those behaviors or not.”

Ernest never reported his mistreatment because he didn’t know who to talk to or who would listen. He said when other students complained about similar experiences to authorities, he only heard about them receiving shallow responses from Penn Police.

Now living in West Philadelphia and spending significant time in Center and Old City as an editor for Philadelphia Magazine, Ernest said his experiences at Penn have prepared him for the real world, where racial profiling still affects him and all people of color.

“The issue is we accept this treatment and don’t push back,” Ernest said. “We need people to say there is a problem with racial profiling in Penn Police and listen to the students getting profiled. Bring them to the table and engage with them.”

The Department of Public Safety did not respond for comment on the relationship between Penn Police and students of color.

Other students simply feel that seeking out Penn Police’s resources is too awkward or embarrassing. One option is Penn’s Walking Escort Service: for 24 hours a day, seven days a week, officers in neon yellow jackets are stationed throughout the patrol zone at student’s disposal. Anna Schmitt (CW ‘19) was one student who didn’t use it, until her perspective changed last semester.

It was only 9:00 p.m. on a Thursday when she was walking along 40th Street to her apartment on Baltimore and saw a large, boisterous group of teenagers. Out of nowhere, she felt the sharp pain of someone yanking on her ponytail and dragging her to the ground. Paralyzed by the shock, Anna could only beg them to take her stuff and leave her alone as the teenagers kicked her relentlessly. Instead, they told her to shut up. Cradling her head with her arms, rocking on the cold concrete, Anna felt helpless. A pair of graduate students saw what was happening and chased the group away.

Through tears, Anna told Philadelphia Police what had happened when she got home. They took down her information and her statement, but told her that unfortunately, similar incidents happens quite often, and there isn’t much they can do once the attackers run away.

Anna didn’t sustain any serious injuries and only had to miss one class. Nonetheless, the experience made a strong impression on how she gauges her safety at Penn.

“In the past, I was privileged to live in neighborhoods where nothing ever happened,” Anna said. “[And now] I have to think twice if I want to walk alone.” Like Milo, the illusion of Penn’s supposed safety broke for Anna after her experience, bringing her back to the reality of living in the city.

Anna considers herself lucky to have a strong support network of friends as well as the Public Safety Resources to make her feel safe. This means walking home with friends, not leaving the house after a certain hour and using Walking Escorts regularly.

Ernest never felt like he could do the same when he was a student.

“I never had an experience where I needed Penn Police,” he explained. “But also, I was too busy being described as a criminal than being criminalized.”