One of my favorite music pieces of all time is Covet’s “Sea Dragon.” It begins with a steadfast, inquisitive opening, then launches into a chaotic and turbulent fluency, which is strung together by fluctuating rhythms and a sorrowful undertone. It is the sound of how we glide across a violent sea, of how we find ourselves inside a whirlpool before we know it. It is the sound of how we forget to fall out of love.

During my senior year in high school, I met someone on Tinder. We'll call him Owen. He was lanky and charming and laughed at stupid things, and although we were too fundamentally different, we shared enough interests and a similar kind of loneliness that we clung to each other on and off for about a year. He broke it off with me right before I came to Penn, and although I have tried, we haven’t exchanged a word since. Nonetheless, numerous things have stayed with me from that relationship, one of those things being the elusive music genre of math rock.

The first thing I learned about Owen, both on his profile and on our first date, was that he played and listened to all kinds of music, especially math rock. Math rock is a genre of music that incorporates odd time signatures, complex rhythmic structures, and a blend of technical and melodic sequences; its focus does not fall on lyrics, but rather the instrumental aspect, which is usually dominated by guitars and drums. Within our first few meetups, I was listening to artists I never would’ve before, like CHON, Polyphia, and Covet: I fell in love with the energy of CHON’s “Perfect Pillow,” the color of Polyphia’s “Paradise,” and the pulsating calm of Covet’s “Hydra.”

By mentioning her in passing, Owen also indirectly introduced me to a musician named Catherine, who lived in our city and had just launched a band of her own. She would be pretty instrumental to my involvement in the math rock community. In fact, the first local show I ever went to was Catherine’s. It was a small backyard show, and my friend and I actually arrived there too late to hear her band’s set, but it was a mind–opening experience nonetheless. Upon walking in, I observed that nearly everyone knew at least one other person that they hadn’t come with: as more people shuffled in, people hugged in reunion, introduced each other to new friends, and huddled together on communal blankets on the lawn. “How do they all know each other?” my friend asked. “It’s like an underground community.”

In March, I drove to San Francisco to see Covet and Polyphia perform live. At this show, I experienced moshing for the first time. When I was bouncing around in the mosh pit, someone pushed me too hard and my knees met the ground, but a second later, two separate people bounded towards me and helped me back up before disappearing into the mosh pit.

I felt a small, warm glow as I drove home that day. When I told my friend about it the next day, he said to me, “Yeah, the math rock community is really great. If you were at a punk rock show, they would’ve trampled you. Math rock culture is the exact opposite.”

As Catherine’s band got bigger and started performing at bars, I followed them like a fangirl to every show. I showed my friends their videos, and I checked their Facebook page almost obsessively. Catherine had only picked up guitar a few months prior to when she started her band, and it inspired me how quickly she had created meaningful music and garnered followers.

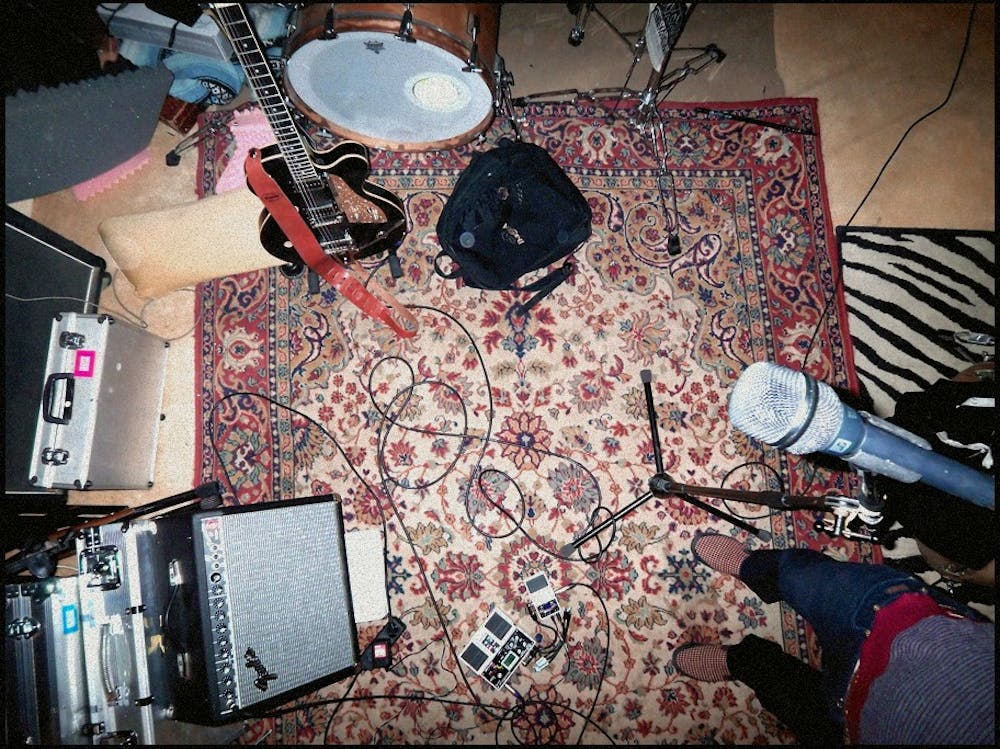

As I went to more shows, I discovered more bands and met new friends in one of the most inclusive communities I’d been a part of. People were, on the surface level, incredibly different—there were women in their early twenties who worked at gas stations, older men with untamed long hair who’d graduated from universities, and there was me, whom they welcomed with open arms: barely eighteen, living in an expensive and uneventful neighborhood, with parents that would never take music seriously. Feeling inspired, I bought myself a cheap electric guitar and began to teach myself to play.

All of this annoyed Owen—understandably, since he was how I knew of Catherine in the first place, and thus, how I’d been acquainted with the math rock community at all. Additionally, for undisclosed reasons, he couldn’t get into bar shows, which meant I was meeting a lot of people he knew of or wanted to meet, even though he had been following them for longer.

When I came to Penn, we stopped talking altogether. My late night texts went unanswered, and his calls, he eventually insisted, were accidental. Despite it all, I continued to practice my favorite pieces and write shitty ones of my own.

Before, I had appreciated music but didn’t think there was any way in which I could take part; the only form of art I was confident I could partake in (to a decent degree) was creative writing. What specifically drew me in about math rock was its culture: everyone could figure music out on their own, everyone could be a musician. Many of the artists I admired had never received formal training or didn’t know advanced theory. The genre was accessible regardless of skill level or money, and good friends often customized album art for musicians for free.

I also appreciated that it was mostly instrumental. Poetry is my main form expression, but it also gets exhausting to have to use words all the time. It was a relief to be able to hold my tongue and let the music stand on its own.

And perhaps subconsciously, it reminded me that Owen and me, despite having such fundamentally different goals in life, despite being incompatible in many ways, had still managed to more or less stick together for a year. I was grateful for the time we spent together, despite our rocky end. At the same time, the reminder broke my heart.

About two weeks into college, I discovered that his Instagram handle, which I’d long believed was overly edgy and dramatic, was actually named after a math rock song. I hadn’t felt sad about him for a while, but seeing his handle scattered perfectly across the Spotify page made me want to cry. It hadn’t been the healthiest relationship, and he hadn’t necessarily intended to introduce me to the math rock community, but he had. And I could never listen to music without thinking about him. In the end, we were incompatible as long term partners, but seeing such a familiar username in a place I didn’t expect to see it was both reassuring and painful. If we’d met under different circumstances, we probably could have been good friends.