When Aiden Castellanos–Pedroza (C ‘19) searched for colleges, he looked for three qualities: a robust financial aid program, a strong Psychology department, and the capacity to accommodate queer and trans students. Aiden’s college application process began like so many others do—with a Google search. One school consistently topped the results: Penn.

“Campuspride.org. That’s how I found out.”

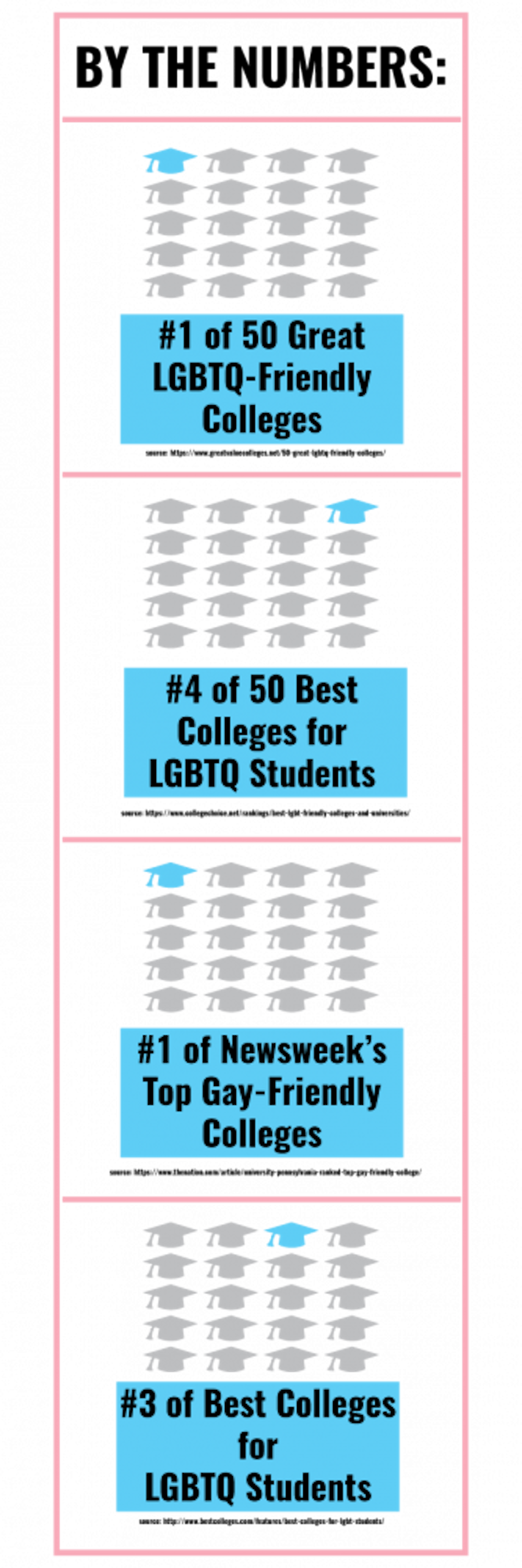

Campus Pride, a national nonprofit dedicated to promoting inclusivity on college campuses across the U.S., lists on its website a “Campus Pride Index,” which rates institutions on a scale of one to five in terms of queer–friendly policies, programs, and practices. Penn earned all five stars.

“At least when I was searching, Penn was actually number one in regards to trans support services. I was pretty blown away,” says Aiden, who identifies as transgender. He wasn’t aware until he was accepted that Penn was an Ivy League school.

When Aiden first arrived at Penn his freshman year, he found the University’s reputation to be generally accurate. “When I ended up getting accepted,” he says, “they were really, really accommodating with being able to get my name changed, with being able to get my gender marker changed.”

But as Aiden eventually found out, there are gaps in Penn’s protection of trans students.

Imagine consistently being referred to by a wrong name, or by pronouns that are not your own. Imagine feeling like you do not belong to your body. Imagine what it would be like use the restroom with constant fear of harassment.

These are common narratives of the trans experience used to elicit empathy from the cisgender majority—those whose gender identity matches the sex they were assigned at birth. Outlets like Vox, Time, and The Huffington Post have all relied on “imagine if” rhetoric—scenarios or hypotheticals that try to recreate the trans experience.

These stories tend to be palatable ways of garnering sympathy for trans people, whose gender does not match their assigned sex. But they communicate a fundamental truth: trans people face specific, pervasive obstacles.

Elliot Oblander (W ‘18), who uses they/them pronouns, deals with those obstacles every day. Perhaps the most routine one is where they can use the restroom. As an undergraduate Statistics student in their fifth year, they spend much of their time in Huntsman Hall. Despite the building’s 324,000 square feet, it only has one gender–inclusive facility—and it was just added in 2016.

“As opposed to just taking an existing bathroom and relabeling it or something, they had to build a whole new one,” they say. “So they’re not taking away from the cis people,” they laugh. “It’s a single stall bathroom in the very back corner of the basement.”

Elliot, whose hair cascades down the left side of their face, explains that once when the gender neutral bathroom was in use, they went to the men’s bathroom next door. "As I was washing my hands a guy walked in and saw me and walked out, and then walked back in looking really confused,” they say.

“Where am I going to pee today?” is a question Elliot has to ask everyday before heading out to class. Should they wear something more masculine–presenting in case they need to use the men’s restroom? Over 80% of Penn’s non–residential buildings still lack gender–inclusive restrooms. Even when they do, they can be hard to find.

Penn Facilities and Real Estate Services is aware of the need for more gender–inclusive accommodations on campus. “There are multiple prongs of the process,” says University Architect David Hollenberg, who oversees all of Penn’s campus facilities and their proposed changes.

The process of finding a suitable bathroom can be even more difficult in some of Penn’s older structures, such as Fisher Fine Arts Library, whose historic significance can hinder renovation. But if not all students can easily use the facilities in one of the most central libraries on campus, is the building fulfilling its duties?

For non–cis students like Elliot, asking “Where is the closest gender–neutral bathroom?” is, effectively, outing oneself.

The question of when and if to reveal one’s gender status varies by situation. Dylan (E ‘18), a Computer Science major who preferred not to be identified by their last name and uses they/them pronouns, explains: “Every time I form a professional relationship with a professor, I go through the process of asking myself: do I tell them my pronouns off the bat? Will this alienate me from them? Will they think I’m some special snowflake who wants attention? Or will they just respect that at face value and move on? I almost never experience the latter.”

The challenges extend also to professional environments. This year, when they went through On–Campus Recruiting, Dylan asked a firm about its gender diversity initiatives during an interview. The interviewer replied: “I myself have three homosexuals on my team.”

“You’re going to need to pay $1,000 if you want nipples,” Aiden says a hospital receptionist told him the day before he came in for a bilateral mastectomy, known colloquially as “top surgery” in the trans community.

Through the Penn Student Insurance Plan, Aiden believed he was able to have all components of his surgery covered, from the administering of anesthetics to the actual performance of the procedure—with the exception of nipple grafts. PSIP, overseen by Aetna, does not cover expenses for cosmetic procedures. Nipples, according to Aetna, are a cosmetic concern, so Aiden paid for the procedure out of pocket. (After this article was initially published, a spokesperson for SHS told Street that PSIP "fully covers all standard costs of chest reconstruction for transgender care, including nipples." The spokesperson added that Penn has an Aetna Student Health representative on site who students can approach with questions about their insurance.)

Aiden has stayed positive about the benefits offered through Penn’s plan.

Without the inclusion of transition–related surgeries and procedures in the PSIP—something that has placed Penn at the forefront of trans health care policy at the university level—Aiden could not have gotten his surgery at all. And beyond Penn’s progressive insurance plan, Student Health Service (SHS) is home to an LGBTQ Working Group, a coalition of a dozen–plus providers with expertise in LGBTQ+ care. SHS staffers also receive training on how to work with queer students.

But without a common knowledge of the accommodations SHS can provide, students may not reach out for the care they need.

“I’m not completely sure of what they cover and what they can do,” says Martina Liu (E ‘20), who identifies as a nonbinary butch lesbian and uses they/them pronouns.

As a low–income student, Aiden faces additional hurdles. He uses CVS needles to inject doses of testosterone, but the cost was initially a barrier.

“I didn’t think that I would be supported in terms of being able to get needles until I had to say: ‘I’m way too poor to afford this. I don’t think I can medically transition because I can’t afford it.’ It wasn’t until I said that [that] they were able to make accommodations.” SHS now provides him with needles free of charge.

But the University’s initiatives only go so far.

“Penn’s interaction with trans people is limited to ‘Do you want to change the name on your PennCard?’ and ‘Do you want surgery?’” says Dylan. “That’s super limiting for nonbinary folk. I don’t necessarily want to change my name. I’m very comfortable being called Dylan, but I would like it if my professors knew beforehand ‘Hey there’s someone who doesn't go by he/him, she/her in your classroom.’

“I’m only as much of a trans person as I want to be cut up—to Penn anyway,” they say. “For everybody that doesn’t need or want a surgery, there’s zero recognition.”

It might seem that the Penn queer community is supportive in ways that the University, as a larger institution, is not. If you’re struggling to come to terms with your sexual or gender identity, there’s a student–led mentor program to help you along. There are groups like Penn Non–Cis, the Penn Queer and Asian Society, and Out in Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics (oSTEM), among others, aimed to support specific subgroups of queer students. Penn Non–Cis is the only group explicitly designed for trans and non–cis visibility and advocacy.

The queer community at Penn celebrates Halloween with an annual, much–anticipated party called Swalloween. This year, it was hosted in an off–campus house. A $3 cover granted entrance to a dark staircase descending into a maze–like basement filled with sweaty revelers.

When Dylan arrived at the party with two friends, they went through the familiar motions: knock on the door, take a step back, and wait for the “Cash or Venmo?” request. When the door did crack open, though, they overheard something unsettling:

“It’s two guys and a girl. Should we make them prove they’re gay?”

These remarks are not uncommon within Penn’s queer community. Although trans students at Penn can find refuge from institutional ignorance within the queer social scene, it doesn’t always provide the safe haven they need.

Students say that queer social spaces on campus are often dominated by white, cis men. “Things that I wish were better?” Martina wonders. “That it was less focused on white gay men.” And when racial and class identities intersect with gender or sexual identities, isolation becomes even more prominent.

In part because of their homogenous nature, queer spaces on campus are often teeming with microaggressions. A microaggression is an offhand remark, gesture, or behavior—intentional or not—that subtly communicates a negative message toward a member of a marginalized community.

Amber Auslander (C ‘20), who uses they/them pronouns and is a member of Penn Non–Cis, believes that microaggressions “don’t come from a place of maliciousness.” They are a result of socialization—for example, how individuals are raised learning that blue is for boys and pink is for girls.

The University has not embarked on any unified effort to combat transphobia. The educational efforts that do exist are the result of homegrown efforts within the trans and non–cis community at Penn. Non–cis students like Amber must advocate for their own identities.

“We have to educate the community about how we exist and why we exist,” they state.

In addition to providing a space of non–judgment and inclusivity, Penn Non–Cis also administers Trans 101 presentations to groups that request them. The presentations run approximately an hour and cover themes ranging from gender identity and expression and the differences between the two, issues people within the trans community face, and how to be a good ally.

But the groups that need the most education are often the least likely to actually search for it. To request a Trans 101 presentation, Dylan notes, “you already have to be a little woke.”

“To reach out to Penn Non–Cis you have to have some idea that Penn Non–Cis exists,” Amber echoes. Without any mandatory sensitivity training or education among Penn staff and faculty as well, trans and non–cis students must deal with transphobia in and out of the classroom.

Trans students must constantly police themselves. Trips to the bathroom, interactions with potential employers and academic mentors, dealing with health and counseling services, and navigating informal spaces all become moments of potential harassment or denigration. And though Penn as an institution is among the most supportive universities for queer students, there is always more to do. For example, only 0.32% of faculty identify as transgender, nonbinary, or gender nonconforming, according to a University report on faculty diversity.

Addressing the most minoritized group, trans students of color, and the unique issues they face is a place to begin. Julia Pan (C ’19), who as chair of Lambda, Penn’s queer student advocacy group, is constantly seeking to engage with all facets of the queer community, laments: “They feel like they don’t fit in in either space,” referring to queer and race–centered student clubs. “So they just disengage.”

Aiden, whose intersecting identities as a low–income, trans person of color often make it difficult for him to engage in Penn’s elite subgroups in and out of the queer community, explains: “There’s been an amount of times when I’ve wanted to drop out. There’s been times when I didn’t necessarily feel like I could even just be thought of in a considerate way here, whether by other students, whether by Penn professors, whether by staff, and so it’s isolating still being here.”

“Which is why I’ve had to find other resources apart from campus, because I just don’t really get to see that that often at Penn,” Aiden continues.

Some say that mandating sensitivity training for professors could help support trans students. “To me that just seems like a no–brainer,” Elliot says. “That seems like it should be trivial.”

A system for keeping track of student pronouns would also help. “It would take a minimal amount of effort to have a portal on Penn InTouch where you can say ‘This is how I want to be referred to,’” argues Dylan.

The lag to address trans issues on campus has led to a feeling of numbness among students. “I’ve become complacent in the way I’ve been treated as a trans person at Penn,” states Dylan.

The persistent day–to–day struggles take a toll.

“My only coping mechanism left is trying to be able to laugh at how much people hate me,” says Aiden. “It wears down on you.”

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the Penn Student Insurance Plan does not cover nipple grafts. The plan does cover "chest reconstruction for transgender care, including nipples," according to a spokesperson for Student Health Service.