Sarah* could already picture her new apartment in San Francisco's Mission District. She had just returned to Penn after her summer internship. The Wharton senior with a Computer & Information Science (CIS) minor had just landed a full-time offer from a San Francisco software engineering firm, with a signing bonus so steep she could feel the house keys in her hand. But before she could accept her nearly six-figure income and start apartment-hunting, Sarah had some decisions to make. Should she take her offer and cruise for the rest of senior year, recruit for other firms, or negotiate her current offer?

Sarah couldn’t help but wonder if her Bay Area-bound male peers would receive the same compensation. Simon*, a Wharton friend of hers who also has a CIS minor, interned at a comparable company over the summer. While they were interns, several news outlets ran stories on Silicon Valley’s gender pay gap, revealing that female entry-level workers in tech get paid 19% less than their male counterparts. As soon-to-be Penn grads, do those numbers apply to Sarah and Simon?

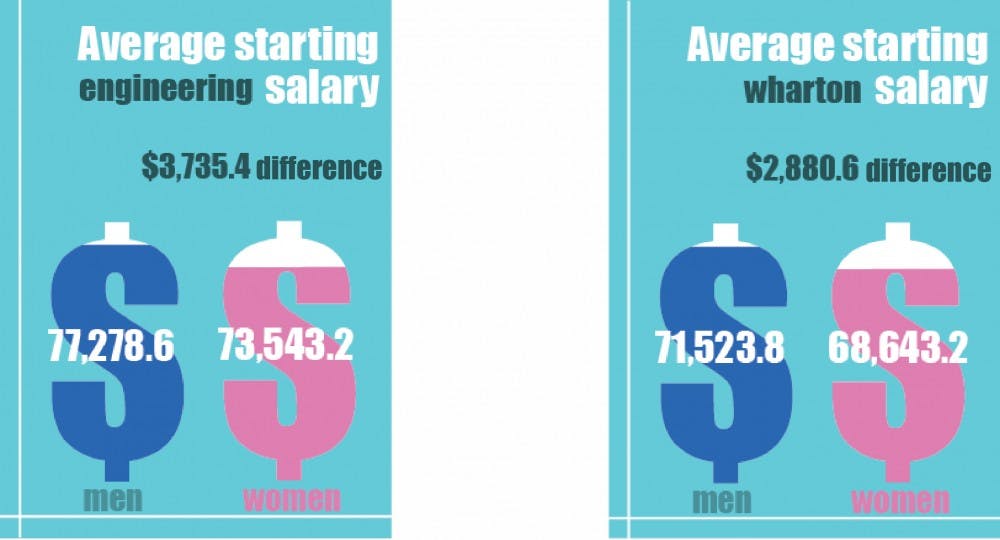

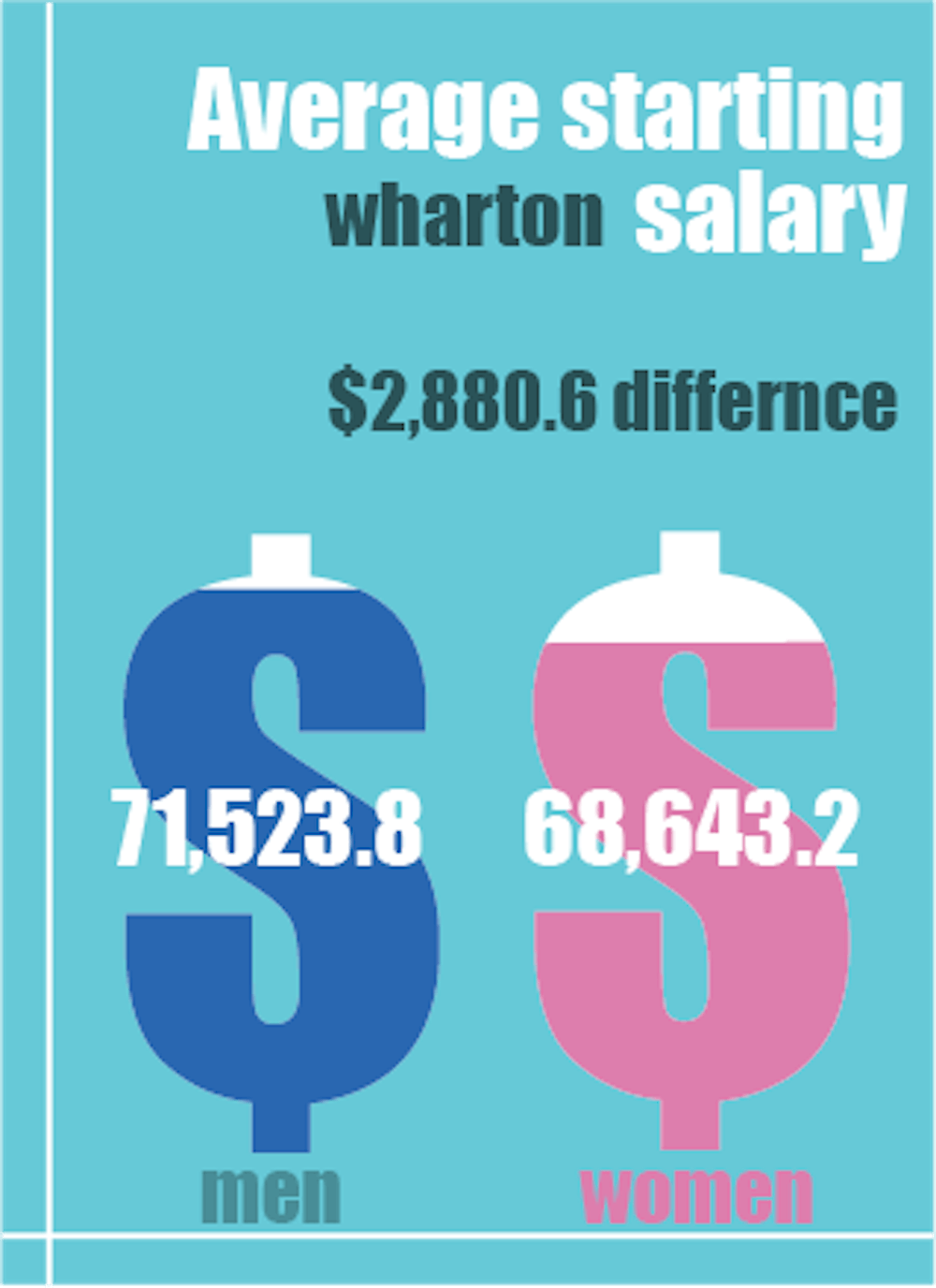

Every year, Penn Career Services publishes the Career Plan Survey Reports, which reveal Penn’s gender pay gap for Wharton and Engineering graduates (the College and Nursing do not publish income statistics because there is not enough data per major). The data they did publish shows that as a female senior in Wharton, Sarah should expect to make 4.03% less in yearly income than Simon. This amounts to $2,880 less annually. In theory, Simon is expected to make $55 more by the end of the first week than Sarah. If they had both studied Engineering, it could be worse. On average, female engineers make 4.83% less ($3,735 per year) than their male counterparts. That adds up to $71 less per week.

These numbers were disappointing to Sarah. But she found herself asking: Does this matter? Sarah will already be in the top 1% of national incomes when she graduates, and will have the added advantage of being an Ivy League-educated woman. Her steep signing bonus was higher than an average US family’s annual income, $57,617. Penn’s data provides evidence that wage inequality can reach even the highest earners. However, Penn’s 4% pay gap pales compared to the general 19% gap in tech, and even more compared to national trends. Should she care that the Penn wage gap is one-fifth smaller than the national average?

Nationally, women make 76 cents to each man’s dollar. The gap is even more prevalent in working class and minority communities. Black women can earn as much as 35% less for the same job as white men. For Latina women, it’s 42% less.

National statistics also indicate that the gender pay gap worsens as women progress through their careers. By the time Sarah reaches her early 40s, she would be paid 23% less than male members of her graduating class. Leaving the workforce temporarily (perhaps to start a family, if she chose) would leave her even more vulnerable and financially dependent.

Unfortunately, Sarah may be destined to be paid less than Simon. But it depends on the field they enter after graduation. Pay is more standardized for finance and consulting jobs, which made up 25% and 17% of graduating Penn students’ professions respectively in 2016 .

Emma*, a senior studying finance, already accepted her investment banking return offer. “In my program, we all got paid the same salary prorated for the summer,” she explained, meaning that the firm paid them a fraction of a yearly wage. “Even though there isn’t a pay gap between female and male analysts, senior women in finance have told me about challenges in the workplace, including developing relationships with male clients who typically prefer meeting over golf, sports, and drinks.”

Data shows that normal consulting analysts were paid $70,000 yearly with a $3,000 signing bonus, while tech consulting paid $75,000 yearly with a $7,500 signing bonus. Both men and women received equal compensation. As graduates enter banking or consulting, Penn women might be facing other kinds of sexism, but discrepancies in starting salaries or negotiation wasn’t one of them.

When it came to graduate job offers in other fields, Patricia Rose, Director of Career Services at Penn, was able to clarify. She explained: “Wharton women — as opposed to Wharton men — by a ratio of two to one, choose fields such as communications, government, healthcare, retail, and various corporate training programs. Many of these pay less than the average Wharton starting salary. At the same time, more Wharton men than women choose venture capital, and slightly more men end up in tech, [which are] fields that pay above the school average.”

The situation is similar in Engineering, she explains. “Computer Science majors have the highest starting salaries, but of the responses to our survey from computer science majors, 73% were men and 27% were women. No wonder the overall average salary for SEAS is higher for men.”

There are fewer female graduates from Penn entering higher paying fields like computer science, venture capital and other tech jobs. But the divide does not stop at occupation choice.

When Sarah waited several weeks to explore her job options, she observed most of her female friends signed their tech offers immediately, whereas her male friends aggressively negotiated offers and got better ones because of it. She noticed that girls were more likely to take their offers at face value.

Rather than doing the same, Sarah decided to ask Simon what his plan was, to get a second opinion. He explained, “I got a significant increase in my signing bonus and equity at my company when I negotiated. The manager I was working for said that negotiating is normal for software engineers. My salary did not change, but I brought my signing bonus up from $75,000 to $100,000 and increased my equity from $200,000 to $230,000 over a four year vesting period.”

Simon’s negotiating success illuminates some aspects of Penn’s gender pay gap: jumping his signing bonus from $75,000 to $100,000 after negotiating might explain why female Whartonites receive on average 14% (or $1,438) less for their signing bonus than men. In tech, where there are significantly more Penn male grads than female grads, it pays to negotiate starting salary, signing bonus, options, vacation, and even moving fees.

Rose at Career Service suggests taking time to consider offers when we receive them, just as Sarah did. “Show your excitement when you get an offer, but don’t accept right away,” she explains. “Take some time to do your research to determine how the offer stacks up against others in the same industry, for that job, and in that location.”

Despite Sarah’s skepticism about her female friends’ negotiating, there is no concrete data to suggest that female students are worse at negotiating their salaries less than male students. Bobbi Thomason, Senior Fellow and Negotiations Lecturer at the Wharton School, wrote in The Wharton Journal that, “[T]he narrative that women don’t negotiate, or don’t negotiate well, is bogus.” She has found that “women negotiate all the time across a range of topics and excel at it.” But, she said, “Studies have found women are less likely than men to self-advocate if it is unclear that negotiation is allowed or appropriate.”

Sarah made a point to recruit for more jobs and negotiate like her male friends, just to see how far she could get. She successfully used her return offer to negotiate a slightly higher starting salary and a much larger signing bonus with a different large tech company. Perhaps the gender pay gap for Penn grads narrowed a hair because of Sarah.

Women can’t change tech-bro culture and old boys’ clubs by themselves. But there are small changes that women can fight for on an individual level. And unless more female seniors challenge the predominating tech-bro culture, go into software or venture capital, and negotiate their salaries, the gender pay gap for Penn graduates will most likely remain the same: 4.03% lower starting salary for women in Wharton, and 4.83% less for women in Engineering.

The data forces us to confront an uncomfortable drawback of being socialized as a woman. Women have advocated for tech companies to release salary data to ensure they’re paying genders equally, but companies like Google have pushed back against doing so.

Although stories like Sarah's prove that women can take initiative in starting their careers and negotiating for higher salaries, cases like Sarah's feel more like anomalies rather than the norm. Women will stand next to their male peers at graduation with the same diploma in hand, but years of Career Services data suggests that this symmetry ends at Franklin Field.