The name “Karim Abdul” probably doesn't ring any bells, but his connection with the second–longest reigning monarch in British history might surprise you. Made public in 2010, Abdul’s diaries revealed his intense friendship with Queen Victoria during the nearly 14 years preceding her death. Victoria and Abdul, based on the book of the same name by Shrabani Basu and a somewhat sequel to 1997’s Her Majesty, Mrs. Brown, details this somewhat–recently discovered historical narrative.

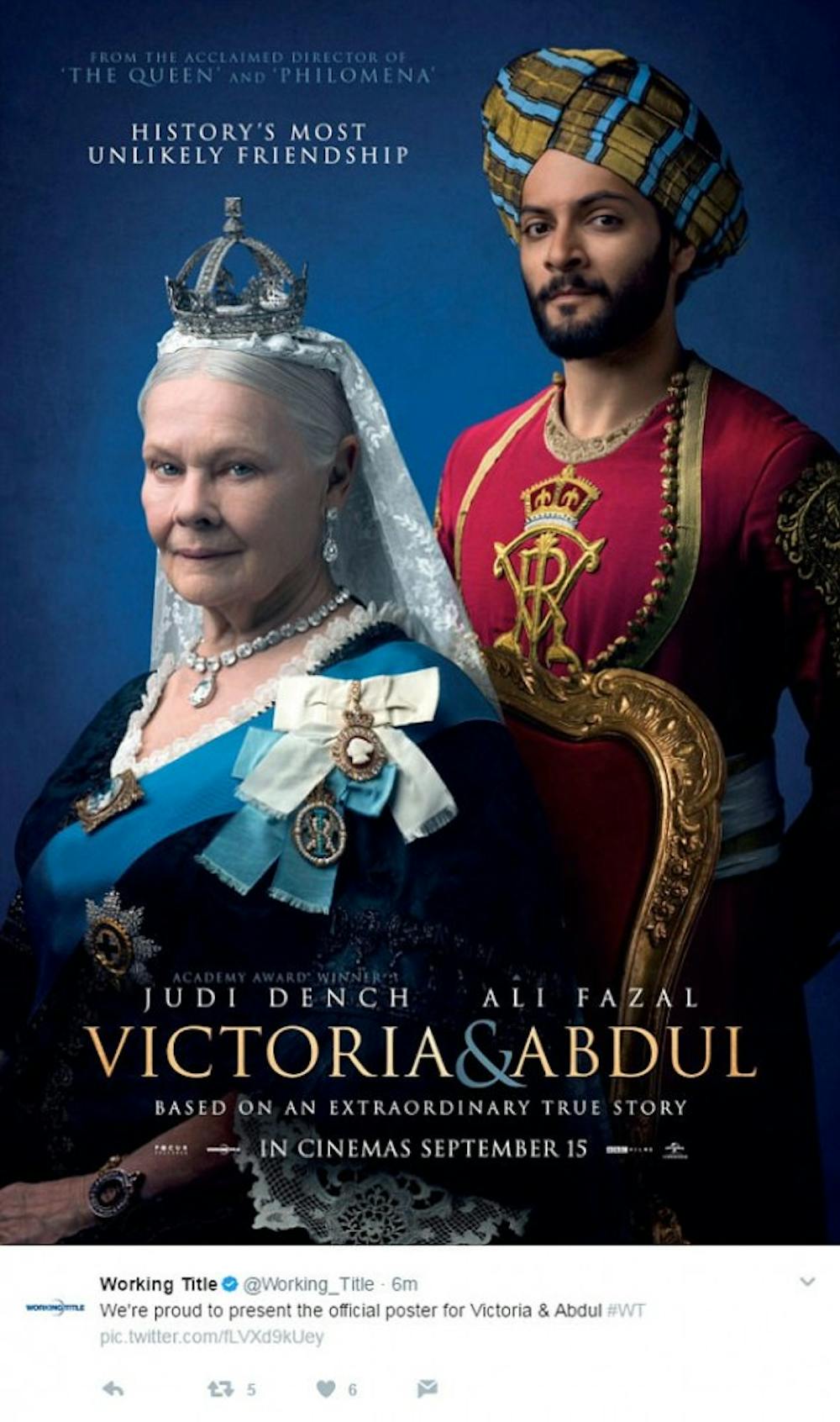

The film begins with a look at Abdul’s life in Agra, India, where his job is to write prisoners’ names into a ledger. We don’t stay here for long—within the first five minutes of the film Abdul is one of two men chosen by British officials to journey to England to present Queen Victoria (played by the incomparable Judi Dench) with a ceremonial coin. Abdul is immediately thrust into 19th century British royal life filled with uppity servants and racist remarks. The subtle jabs don’t seem to affect Abdul, played by the engaging Ali Fazal. His optimism is palpable and endearing, but seems to elude the house staff who refer to him as “the Hindu.” When it is time to present the ceremonial Indian coin to the Queen, Abdul is told multiple times to “not look at her.” Of course, he looks straight into her blue eyes. There would be no story if he didn't.

What follows is sweet albeit strange story of friendship. The Queen, initially taken with Abdul’s charm and good looks, becomes enthralled with his knowledge and kindness. Abdul becomes progressively more and more involved in her life and royal duties, starting as her footman and ultimately becoming her “munshi," or teacher. He kisses her feet, entertains her subpar singing , and tutors her in Urdu. Their interactions are often natural and sweet, but sometimes, as expected, marred with cliche. There seemed to be a collective sigh in the audience when Abdul tells the Queen, “life is like a carpet.” Yet this quip seemed to fit in perfectly with Abdul’s character. He is a teacher to the Queen, so these kind of mantras which might seem silly out of context, are welcomed.

For the most part, the film deals quite well with accurately and respectfully representing Indian culture. For example, when Abdul’s wife arrives at the palace, she is concealed from head to toe in black. The Queen has to request access to see what she looks like under her dress and when she finally does proclaims that Abdul’s wife is beautiful. However the film’s major flaw almost stems from moments like these, where it paints Queen Victoria almost as a savior. She may have been accepting, but was by no means progressive. It seems as if director Stephen Frears may have been searching for a historical foothold that did not exist.

This is not to the fault of Judi Dench, who is witty, funny, and unapologetically British. The film’s shining moments belong to her and her innate ability to balance vulnerability and power. It is no secret Dench can play a historical figure without resorting to gimmick or imitation (we have seen her do it twice before in Shakespeare in Love and Her Majesty, Mrs. Brown), but her performance is nonetheless refreshing. This is best exemplified when Victoria confides in Abdul, telling him, “I am so lonely.” As he comforts her, something becomes clear: the Queen simply wants a friend.

But their friendship does not come without challenges. The Queen’s house staff and her indignant son Bertie, Edward VII, thoroughly disapprove of Abdul’s role in her life and actively try to thwart his influence. Their conversations, while often comical, are tinged with intolerance and prejudice.

Ultimately, after Queen Victoria’s death, they get their way. Edward VII banishes Abdul from the palace and orders that all of Abdul’s memories of the Queen (books, photos) be burned.

Despite this, the film ends on a high with Abdul back where we found him, in Agra. The final scene finds him bowing to the statue of Queen Victoria in front of the Taj Mahal. He kisses her feet, sweetly commemorating both his culture and hers.