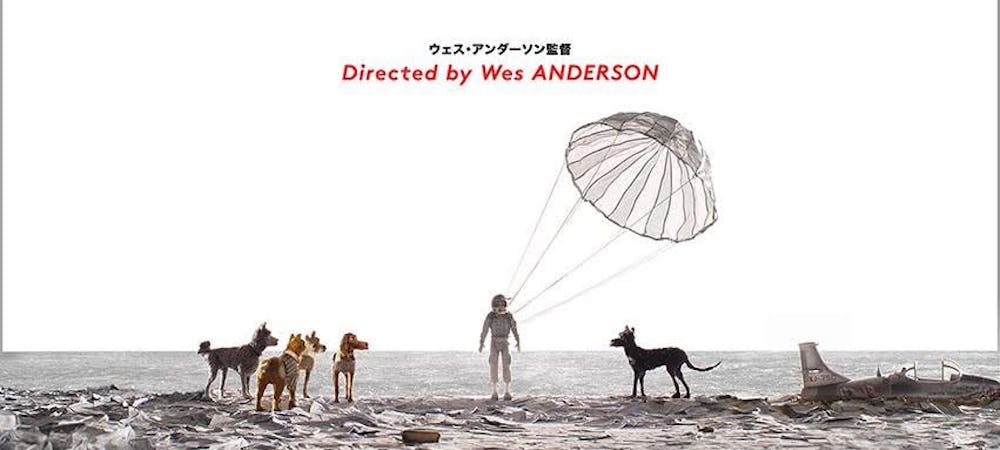

Known for his eclectic mise–en–scène (the arrangement of actors and scenery), Wes Anderson has established himself as one of the most recognizable auteurs of contemporary cinema. Isle of Dogs, Anderson’s upcoming stop–motion film, narrates a dystopian future Japan where “canine flu” has lead to the quarantine of all dogs to the remote “trash island.” An epic journey ensues, as the 12–year–old Atari Kobayashi ventures out to the forbidden isle of dogs in an attempt to find his lost pet. With the help of a gang of local canines, the young Kobayashi disobeys the authorities of Megasaki City in the hopes of finding his beloved Spots.

In the past, Wes Anderson’s protagonists have primarily dealt with familial problems and loss of innocence—their experiences fitting of a bildungsroman. Films such as Darjeeling Limited explore grief, dysfunctional family dynamics, and miscommunication; Moonrise Kingdom, while starkly different in its story from other films, similarly deals with thematic elements concerning coming–of–age and the loss of childhood in a world of unreceptive, dispassionate adults. Regardless, from Bottle Rocket to The Grand Budapest Hotel, the moviegoer witnesses yet another one of Anderson’s idiosyncratic, minutely constructed worlds. Those familiar with Wes Anderson’s oeuvre would find it hard to imagine the man who switched aspect ratios to coincide with specific time periods in The Grand Budapest Hotel didn't even have the directorial authority to shoot with anamorphic lens in Bottle Rocket. With the release of every new feature film, Wes Anderson delves increasingly deeper into the particulars of his style of filmmaking and directing.

Although many praise Anderson for his attention to detail and mastery of narrative, some suggest that Anderson values style over substance, and that he fails to push into different thematic subjects. As someone who still retains an ambivalent position towards Anderson’s work, I find that my criticisms do not necessarily lie in his particular subject framework or even his obsessive attention to mise–en–scène. In order to fully express a more nuanced critique of Wes Anderson’s work, I interviewed Professor of English and Cinema Studies Timothy Corrigan about his personal views on the director’s filmography and what Isle of Dogs may lie in store.

Put bluntly, Corrigan suggests that Anderson’s choice of subject matter concerning family dynamics where his “main protagonists are teenagers or adults that act like kids” makes him a “children’s director or at best, a tween–ers director." He further remarks, “This isn't necessarily bad because [Anderson] has a great eye and a good imagination, and his brand is to be quirky and he’s very successful at creating quirky situations. However, I like to see films and filmmakers go farther than that.” Even at the heart of Rushmore, one of Anderson’s most acclaimed movies, the story follows yet another make–shift family dynamic of Herman J. Blume, Max Fischer, and Rosemary Cross, as we witness Bill Murray’s and Robert Schwartzman’s characters grow up. However, auteurs throughout cinema history, ranging from Francois Truffaut to Steven Spielberg, have made their works on easily recognizable, reoccurring themes. While critics deem Truffaut as one of the most accomplished filmmakers, he constructed an entire five–part series of films following the life of “Antoine Doinel," a character who is an autobiographical, alter–ego of himself. I’d personally assert that if this repeated focus on troubled adolescence was, as Corrigan notes, “Truffaut’s formula,” then we should consider accepting that Anderson too “has his formula."

However, Wes Anderson’s work does not go without fault. Corrigan points out that by “being somebody who works in an imaginary place, whether in the middle of the sea, in a hotel, or underneath the earth,” Anderson creates worlds that “ripple with anxiety," but never particularly “push into deeper, more complex psychological or political situations.” Looking to Darjeeling Limited and The Grand Budapest Hotel, I believe that these words ring true. While Darjeeling Limited may have been an attempted tongue–in–cheek of Westerners trying to find themselves in India, Wes Anderson fails to reach the level of self–awareness to pull off such a subject. In one of the film’s pivotal points, the three brothers attempt to save a group of children from drowning in the river of their village. Peter (Adrien Brody) is unable to do so and remarks the movie’s most uncomfortable, possessive phrase, “I lost mine." In this moment, there is no metaphorical nod; in order for the movie’s characters to develop spiritually, the Indian child or “other” must perish. In The Grand Budapest Hotel, Wes Anderson manifests an entire political state ravaged by war but still finds a way to dodge any contextual political meaning with his work. Aside from the emphatic “you can't arrest him just because he's a bloody immigrant” line from the film’s protagonist Monsieur Gustave regarding the mistreatment of his lobby boy, the viewer never gets a more complex acknowledgement of the real world from Anderson.

With Isle of Dogs, Anderson returns to the East, inspired by the work of Akira Kurosawa. While one of his most lucrative and acclaimed films dealt with stop–motion (Fantastic Mr. Fox), Anderson may once again have trouble dealing with a world that he has not explicitly created since its inception. Whether India or Japan, there is a level of cultural consciousness and realism that Anderson must employ. I will no doubt look forward to another carefully crafted, coming–of–age story from Wes Anderson in Isle of Dogs; I simply hope that he pushes the boundaries of his narrative.