Sometimes a song is just so good, you have to hit replay over and over again. Your interpretation of the song shifts with each fresh listen and novel appraisal, causing the same fundamental music to twist and shift into something new. Great music inspires us to dissect each minute detail until we absorb every drop of emotion and melody. This is what musicians have done with the jazz standard “Summertime.”

“Summertime” was composed in 1934 by George Gershwin (with lyrics by DuBose Heyward) for the opera Porgy and Bess, a controversial work that has received criticism and praise throughout its history. Since then, over 25,000 renditions have been produced, making it one of the most covered songs in history. The path that these songs forge cover some of the most important decades in the development of music through the 20th and into the 21st centuries. Using “Summertime” as a lens, the radical changes in music that occurred throughout this critical period in American history become clear.

Porgy and Bess (1935)

In the original performance of “Summertime,” a minor character sings the song as a lullaby to her sleeping child in the first act. The song has minimal, understated background instrumentation, allowing the high, haunting notes of the soprano to hang out in a traditional operatic fashion. Although the song is clearly written for an opera, elements of Gershwin’s jazz style come through in the slow, building melodies that evoke deep, foreboding feelings. With its minor, subtle strings and long, emotive notes, the song also seems to draw from traditional slave spirituals. “I Feel Like a Motherless Child” is one such spiritual that has been identified as a potential inspiration for the song, although this was never confirmed by Gershwin.

In a few words: original and operatic

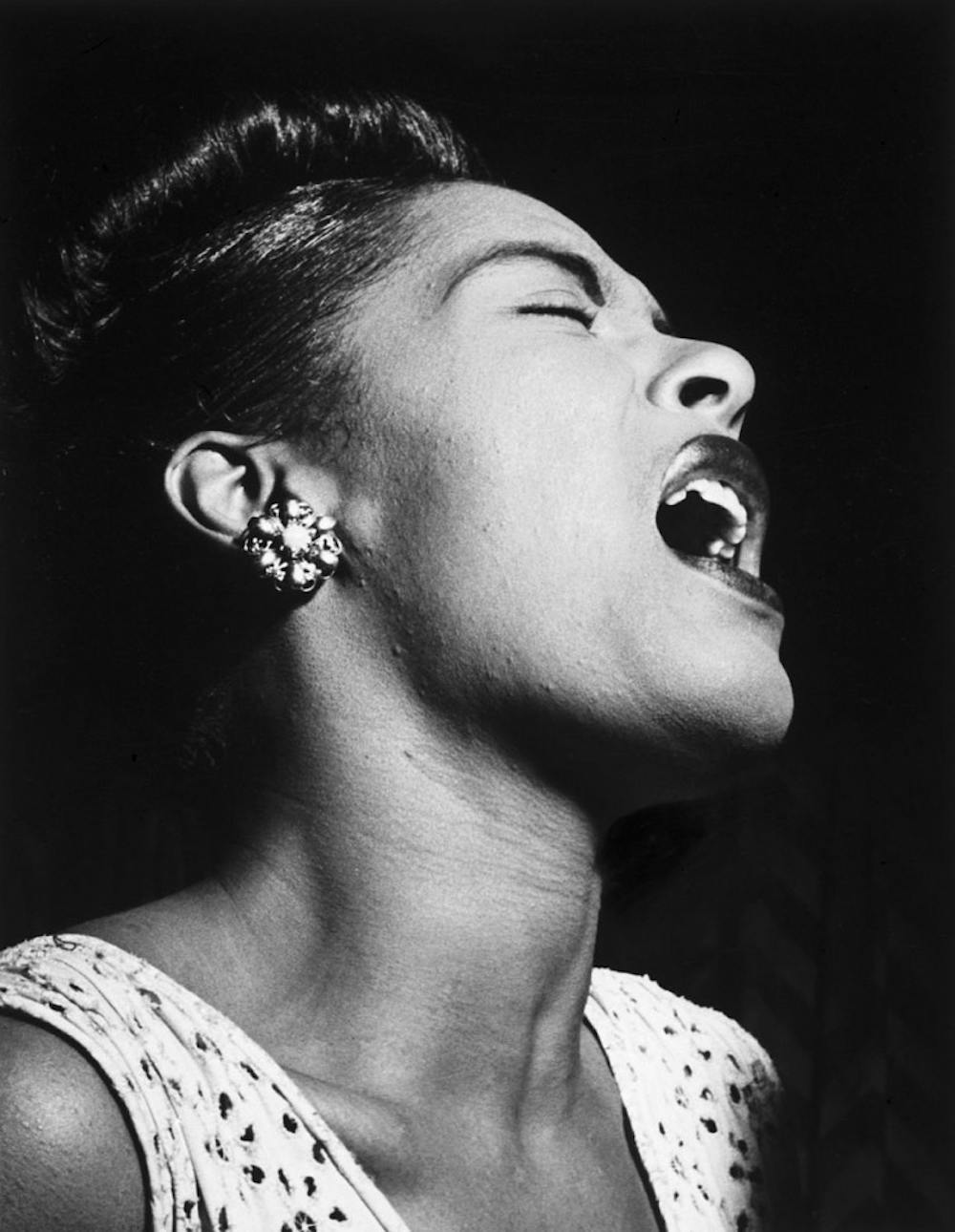

Billie Holiday (1936)

Only a year after the show first premiered on Broadway, jazz great Billie Holiday recorded her own rendition of the song, garnering critical and commercial acclaim. In the song’s first appearance on the pop charts, Holiday performs with a vocal jazz style in line with the era and her previous work. Leading the way for future covers, her major contributions to the song are her experimentation with phrasing and tempo. She uses a nuance in her timing to make the song personal. It’s not surprising Holiday felt a personal connection to the lyrical meaning in “Summertime” due to her own troubled history, and she brings this personal passion with full force in her cover.

In a few words: the beginning

Chet Baker (1955)

The post–war era in America marked a totally new frontier for jazz. Chet Baker’s “Summertime” is a great lens into this new world—he brings a West Coast, “cool” jazz flavor to what was once a traditional piece. The song begins emphatically, with a clean, solo trumpet, emphasizing the melody and the importance of simplicity and free–spirited improvisation in Baker’s style. With no singer, the trumpet fills the role of the vocals completely, and Baker builds on this by using his improvisational techniques to bring a unique distinction to the part that would be inaccessible with a human voice. t reflects more on Baker’s role as a visionary in jazz, as his style in this song is more contemporary than many later renditions.

In a few words: smooth and cool

Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong (1958)

Although this song is technically a duet, in reality, it's better thought of as the combination of three distinct forces: Louis Armstrong’s trumpet, Ella Fitzgerald’s vocals, and Armstrong’s vocals. When playing his instrument, Armstrong pushes a highly expressive and pointed melody that contrasts with Ella’s soft, slow, and smooth vocals.

What makes this song so phenomenal is how both of these parts play off against Armstrong’s deep, gravelly voice, which seems to anchor the song alongside the two other competing melodies. The strings and low horns in the background give the song a soft, nagging tone that drives the piece forward and calls for the next part of the music. What both these artists do so brilliantly is use their incredible talents to bring these emotional undercurrents into what appears on the surface to be just another traditional jazz rendition of the song.

In a few words: the greatest

Al Martino (1960)

Al Martino, a less famous version of Frank Sinatra, may be best known for playing Johnny Fontane in The Godfather. He lives up to his musical heritage in this song, as it's been essentially rewritten in a swing/crooner style à la Frank Sinatra or Dean Martin. The upbeat horns and relentless progression of chords on the piano breathe a novel life and spirit into the song.

In a few words: almost Sinatra

The Marcels (1961)

The Marcels are a somewhat well–known boy band in a style that would soon become very well known during the Motown era. They convert the song into doo–wop, combining upbeat drums, a guitar instead of the usual piano, and a stronger baseline to give the song a much more modern rock feel. Their multi–part singing group replaces most traditional horns, with the exception of a really interesting saxophone solo, in which the group actually harmonizes behind it. The feel of this rendition goes beyond the lyrics and previous interpretations.

In a word: weird

Billy Stewart (1966)

The most commercially successful rendition, reaching number ten on the Billboard Hot 100, Billy Stewart turns the song into a wild typhoon of sound and rhythm. From his expressive, undefined, and erratic introduction, he gradually gets into the song, during which the focus is almost entirely on his powerful voice. He takes great liberties with the lyrics, timing, tempo, and phrasing, and uses scat, his signature technique, to bring a truly incredible and powerful emotional force to the lyrics.

In a word: wild

Janis Joplin (1969)

Janis Joplin’s blues–influenced singing, backed by the psychedelic Big Brother and the Holding Company band, is marked by a distorted guitar and driving rock drums, with a subtle walking baseline to tie the backing section. Joplin herself first performed the song at Woodstock, only recording it later, and uses long, drawn–out notes and dynamic style to give a fresh and unprecedented emotional content to the lyrics. In what seems like a throwback to blues legend Billie Holiday, Joplin also ties her own deep personal history to the powerful lyrics of the song.

In a word: soulful

Fun Boy Three (1982)

Fun Boy Three is a British new wave pop band that had the most recent cover to make the pop charts. The boys' gloomy vocals and harmonies contrast the upbeat, groovy drums that draw on influence from ska and reggae rhythm. While the haunting vocals in the verse are reminiscent of earlier jazz renditions, the chorus and bridge sections are a genuinely novel approach that use a multitude of instruments to put different, modern vocal lenses on the song’s old melody.

In a few words: eclectic influences

Norah Jones (2003)

Singing alongside a solitary piano, Norah Jones reinterprets the classic song by reducing it to its core elements and retracing the steps of the song. As a modern jazz musician, she uses her incredible vocal ability to put a subtle, simple touch onto a song that had strayed a long way from jazz in the 68 years since it was first performed.

In a word: throwback

Willie Nelson (2016)

Although he didn’t perform “Summertime” until just last year, Willie Nelson was a primary voice of outlaw country in the late 1960s and 1970s. He uses this background to put a totally modern and unusual spin on the song. His harmonica and plucky guitar strings give a genuine country twang to the old jazz standard. His vocals are the wistful and honest singing of an old singer revisiting his musical legacy as he also asks the listener to revisit the musical legacy of “Summertime.” The airy, high–pitched, hanging harmonica sounds vaguely operatic, and the melody produced by this instrument makes Nelson’s “Summertime” both one of the most distinct and most true renditions of the song when compared to Gershwin’s original.

In a few words: the old and the new

Throughout this long period of musical history, the constant themes and melodies of “Summertime” were warped, transformed, and reshaped by each musician that dared to put their own contribution into this great body of work. Some of the great musicians of modern history fixated on this song at one point during their career because, says Chichester University professor Ben Hall, "the tonal ambiguity at its heart means that when a performance of 'Summertime' ends you’re instinctively waiting for the next one to start. It hasn’t resolved itself.”

“Summertime” will continue to be a part of music’s past and its future. The vast contributions made to this song in style and technique continue to redefine the musicians' respective genres and the artists that follow. So when you listen to the songs on this playlist and reflect on the great musical progress we’ve already made, you may feel a nagging feeling that something has been left unsaid. There’s no cause for alarm if this is the case—that just means that it's time for you to record your own cover and pour your own contribution into “Summertime.”