The Harvard freshmen in Dr. David Hubel’s biology class were a bit surprised when their teaching assistant first showed up to lab.

The sweet–looking blond girl wasn't a graduate student, or even an undergraduate. She was a local high–schooler named Jane Chuprin who’d gotten an internship with Hubel, a renowned Nobel Laureate, by accident. He overheard her interviewing for a different position she turned out to be too young for, and offered her a spot in his own lab. Part of her job was helping out with his biology class.

Stay connected with QuakerNet:

The Alumni Directory

www.myquakernet.com

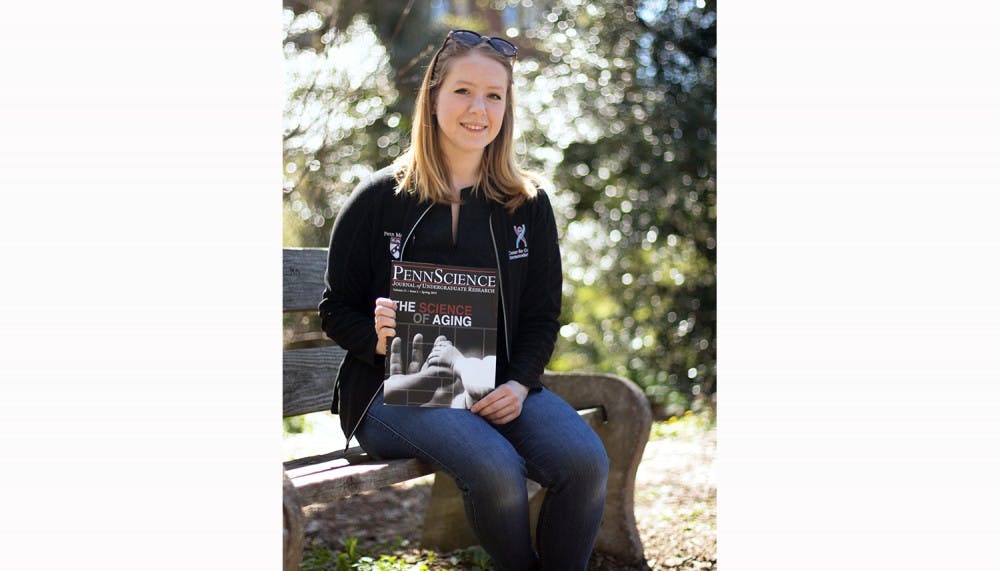

“I was terrified because they were all so much older than me,” says Jane, now a College senior, budding cancer researcher and editor–in–chief of the Penn Science Undergraduate Research Journal. “I was surprised how much I learned.”

Jane, fascinated by her high school biology class, had applied for dozens of lab internships, qualifying herself as a sophomore (wisely declining to specify whether she was a sophomore in high school or college). Rejection after rejection didn’t faze her—an innate curiosity about the world and determination to learn more about it kept her going.

Hubel was Jane’s first mentor, the first to show her how to view the world scientifically. One day in lab, Hubel cut his finger, and Jane rushed off to get paper towels. When she got back, he stood there staring at his cut, and asked Jane if she’d ever seen blood under a microscope before.

She hadn’t. He told her she really should.

“That moment I realized that what I saw as a nuisance, he saw as really inspiring and he really went beyond the surface of it,” Jane said. “And I think I realized, in that moment, there’s so much going on that I didn’t realize.”

Jane, whose father is a mechanical engineer and mother is a dermatologist, knew she wanted to pursue science in college. She transferred to Penn after her freshman year at Boston University, planning to study visual processing. But something else caught her attention when she got to Penn: cancer. She began working in a cancer lab during her sophomore year and has been there ever since.

“It’s so interesting to me,” she said. “It’s a really complicated problem that I think is really worth solving and also could do a lot of good.”

Her lab specializes in Car T–Cell therapy—a procedure for destroying cancer cells. When someone has cancer, their immune system might not recognize cancerous cells because they originated in the body. Car T–Cell therapy takes out T–Cells—the cells involved in the immune system—and gives them a certain receptor so they can identify and destroy the cancer cells.

Jane’s enthusiasm bubbles through when she explains the process and helps others understand how important it is. It’s personal for her, too—her mom is a breast cancer survivor, and her childhood friend Caitlynne McGaff survived cancer as well.

“I appreciate the work that she does, and I appreciate that she’s so passionate about it,” Caitlynne said. “Because, coming from a personal standpoint, I know what a difference she’s making.”

For Jane, a molecular biology major, lab work involves long hours of experimenting and testing, strings of disappointments before a breakthrough.

“It’s frustrating...that happens in science. In research, especially, you don’t know what’s going to happen, so you brush it off and continue moving forward,” she said. “It’s not worth being upset about something. It sucks, and you take a few moments to be like, ‘damn,’ but then you keep moving forward.”

Jane’s willingness to fail and keep trying drives her life outside the lab, too. When she got to Penn, she decided to try ballet, even though she hadn’t danced since she was a little girl. It took three semesters before she finally got into Penn Ballet—yet she wouldn’t let herself get discouraged.

“I realized I like doing ballet a lot, so I just did it for me,” she said. “You have to stop caring what other people think, which is really hard. In the back of your head, you’re like, ‘I’m probably getting judged, but do I care?’”

But to Jane’s friends, she’s more than just a determined scientist. She’s a kind, easygoing friend who doesn’t take herself too seriously and invests herself in other people’s lives, no matter how busy or stressed she is.

“Even if she’s really busy and I don’t see her for three days, eventually, when we’re both at home at the same time, she’ll come and sit on my bed and we’ll just talk,” said JoAna Smith, who has lived with Jane for three years.

JoAna met Jane when they were assigned to live together randomly during Jane’s sophomore year. Jane always worked in the living room and made food for her roommates, making the apartment homey and welcoming.

“I think it’s kind of helped ground me in the chaos at Penn,” JoAna said.

Caitlynne, who has known Jane since high school, described her mischievous side. When the two were roommates at Boston University, Jane played an April Fool’s Day prank on Caitlynne: she changed the timezone on Caitlynne’s phone so her alarm would go off at 5:00 a.m., instead of 8:00 a.m.

But underneath the jokes, she’s approachable and deeply loyal.

“She is very loyal to her friends and to people she loves, just in the sense that she is so willing to drop everything the second you say you need something,” said Caitlynne.

Although Jane says Penn’s busy, competitive atmosphere appealed to her, her choices and attitudes often set her apart from the stereotypical Penn culture. She’ll keep trying, even if she isn’t good at something, until she succeeds. She stays positive and genuinely loves her work, even when it’s frustrating.

“Especially at Penn, you can get wrapped around everyone complaining all the time and being stressed out, and even though she’s stressed out, she’ll be like, ‘Okay, I did spend 15 hours in lab today and it was terrible and I’m exhausted, but I did get to do this really cool thing,’” JoAna described. “She’s very positive in that way and you can see that she actually cares.”

Jane’s next move? An MD–PhD—a demanding eight–year program where physician–scientists can earn two degrees. Jane plans to return to her hometown of Boston for the program. And despite the grueling years of work and research ahead, Jane isn’t likely to lose her interest in science anytime soon.

“I’ve always had a passion for science,” she laughed. “I’ll be the one at Fling who gets drunk and says, ‘This is how science works.’”

Click here to read more Penn 10 profiles.