I spend a lot of time in the hospital nowadays.

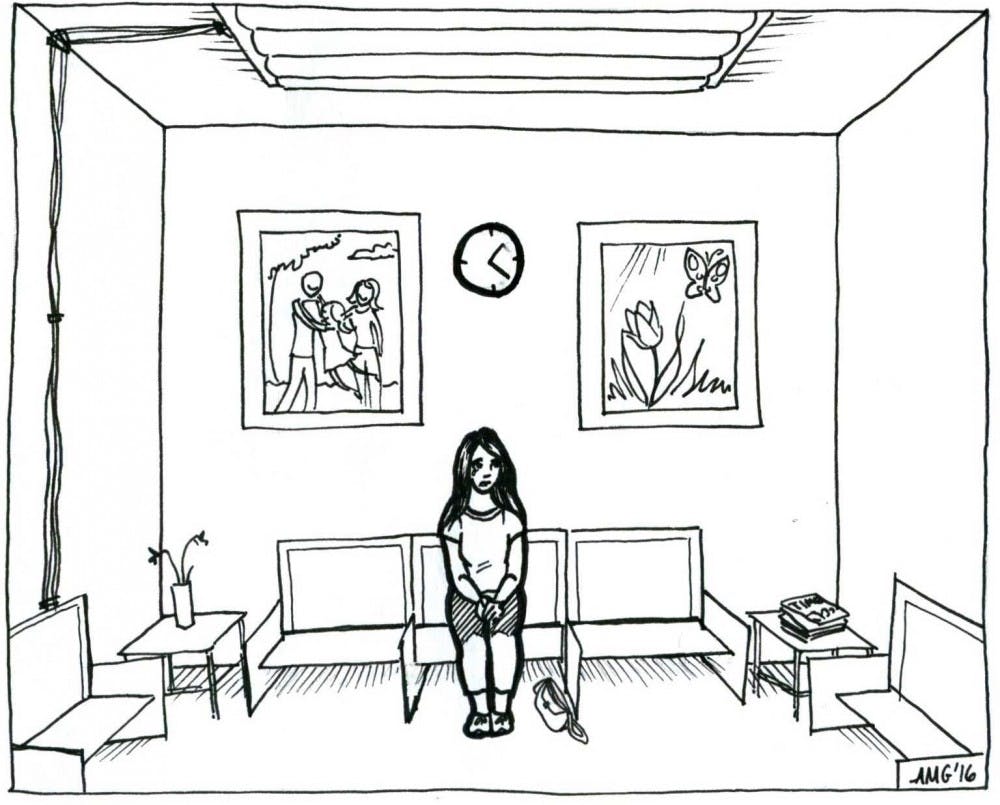

My official title is Research Assistant, but my unofficial one is daughter. Being the daughter of a cancer patient means that every time I enter in data and run across a file with the same stats as my father, I think about sterile waiting rooms, fluorescent lighting and the way the breath caught in my throat when I first saw his CT scans.

I could draw you a map of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Ask me about the vascular wing or the renal wing. I know the best café items, the peak dining hours. I know the smell of antiseptic and the stench of illness. When they diagnosed him, I bit my cheek so hard I drew blood and thought it was the taste of his love.

I found out about his suspicious mass on a Wednesday, during a transfer student get–together. When I read the words "CT scan," "suspicious findings" and "renal cell carcinoma," I thought back to the first time I told my father, “I hate you.” I was 12. I tried not to notice the way his face crumbled when I said it.

Even now, we fight a lot. He lets me win most arguments, because he loves me. Because for him, winning is seeing me happy. Because love is sacrifice, and that’s something I’m still learning, while he’s had his whole life to memorize this lesson.

Death happens in an instant; losing someone is an eternity.

I explain different procedures to my father with a detached coolness. Then I go home, do my own research, look at anecdotal evidence. I bite my nails down to bloody stumps. I ask doctors clarifying questions that I don’t want to know the answers to. I hold his hand, or I catch his eye across the waiting rooms, and I think:

I’m sorry.

Don’t worry.

Please stay.

But most often, I stay silent. I’m scared: What if I say something terrible and I never get to apologize? I love my father, but our relationship isn’t always easy; it’s not always fair or kind. I’m not always fair or kind. What is there to say now? What words make suffering better? What could I say that wouldn’t sound like an apology blanketed in years of regret?

Losing someone is a lifetime of what–ifs.

Every day is new news, more doctors, more reports, so many hospital waiting rooms. But I go to class. I try to make friends. I do homework. I write papers. I go out. I laugh. I smile. I pull myself out of bed in the mornings. I get dressed. I say, you are not going to cry right now. I say, you will not cry in front of dad. I do clinical research about renal hypertension at Penn Medicine. I pretend like it makes a difference. I research doctors, take referrals, look up clinical trials, weigh the risks versus the benefits of different procedures. I Google and Google and Google and Google.

Sometimes, I pray.

We spend a lot of time together now. He’s always in the city, meeting new doctors, discussing treatment options, being defined as a “risky candidate.” After these appointments, we go out to dinner and feign normalcy. Across from him at restaurants, I study his features. I look for those same qualities in my face, at night, before bed. I touch my low forehead, my sloping nose, and I think, these are the parts of you I’ll always be able to keep.

Last week, on the drive back to my apartment from the hospital, he turned the music down, and caught my eye in the rear view mirror. He said, “I can’t wait to see what the future holds for you,” and then he smiled. I thought about me, aged ten, playing basketball with my father in our front yard. I dropped the ball so many times; he laughed, ruffled my hair and said, "I can’t wait to teach my grandson some day."

All I could think then was, Dad, we’ve got all the time in the world.

And all I could say now was, “Yeah, Dad.”

A pregnant pause, while I looked out the window at the landscape of college kids milling about, going to class, moving on with their lives.

Then, I met his eyes. “We’ve got all the time in the world.”