Street: Tell me about your background as a documentary filmmaker, and what kind of projects you’ve done in your experience at Penn.

Noam Osband: I started grad school at Penn in 2008 and I took a filmmaking course my first year. And I was very lucky, I had a teacher named Ellen Reynolds. I don’t know if she still teaches there. She was in the Design School. She taught there even last year but I’m not sure if she’s still there. Anyways, she taught filmmaking, Video I in the Design School I think it was. And she was a great teacher and I sort of really fell in love with it. I remember the first video assignment I made was, like, a short film about the Italian Market and how it has become heavily Mexican called ‘El Mercado Italiano.’ And I remember on the first sort of filmmaking thing I ever did or the first time I shot my own film, I went to a cop…. There had been a bunch of cops shot in a short period in 2009 and I went to the funeral for the last one. And I really loved filming it. There was something just thrilling about.. I mean it was a very sad occasion of course, but I remember there was a tent of cops, and I was scared to go in and film them because it was a tent of police officers, and there was a woman there who works for a television channel, like she wasn’t a student filmmaker, and I remember she said to me “This is what we do” as a way of encouraging me to go in. And it was a very empowering moment, and I filmed it. I felt film was a way to—I have like this intellectual side of me which is finishing up a PhD, but there’s also an artistic side to me. And I thought film is a way to square that circle.

Street: So I saw on your website that your thesis is on reforestation. Tell me some more about that.

NO: Yeah so as soon as I get off the phone with you I’m gonna work for another 4 hours on that with you. It’s a film about Mexicans and Americans who plant trees for a living in the American South. Sort of across the South there’s a lot of pine plantations, from Texas to Florida, up to Virginia. We have that in other parts of the country, but most of that is in the South. It’s like a little-known world. America uses a lot of paper and lumber.

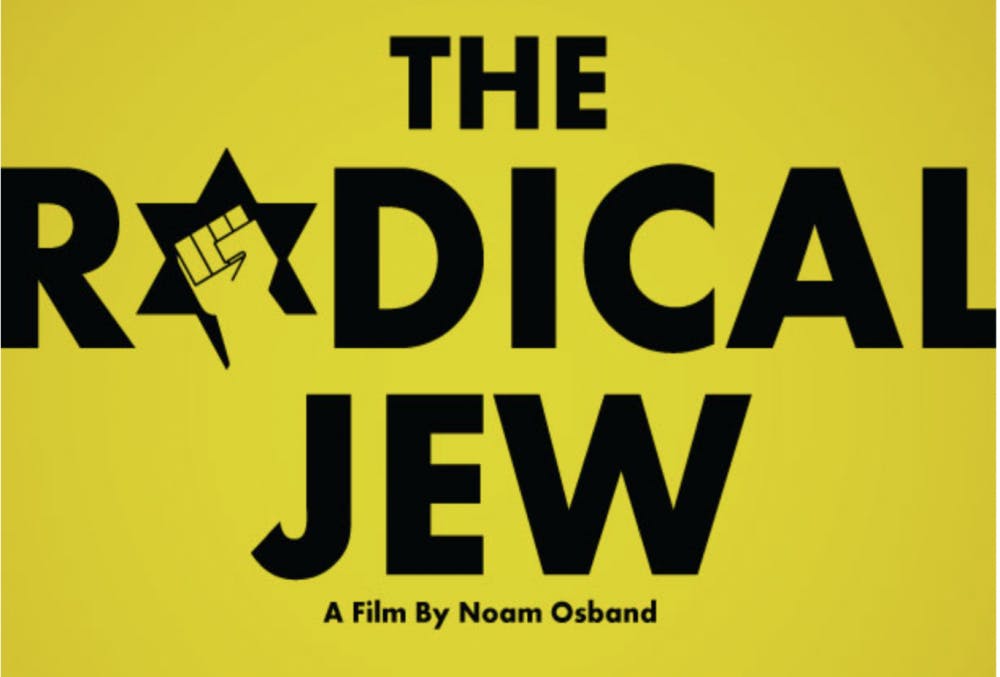

Street: What was your inspiration to make the short film ‘The Radical Jew’?

NO: A combination of interest and availability. The interest is that for most of the time Jews were in the diaspora. Jews were not sort of militant and firm believers in force. Starting in the late 19th century, you had one variant of Zionism, which is actually sort of muscular. I just think that’s interesting. What does that mean? The other thing is availability. The subject of the film was a distant relative. I didn’t really know him. I went there for the summer and I had to kind of introduce myself to him. I had met him once before and he didn’t remember me at all. So I felt like I have access to this person who is very well–known in Israel—in Israel everybody knows who he is across the spectrum because he’s such a provocateur. But he’s not too known outside of Israel, so I thought, here’s a chance to make a thoughtful movie about extremism. Like, what does it mean to be an extremist? How does an extremist see the world? That’s what I’m trying to do with the film. I think it’s about extremism in general. The sort of Manichaean conflict he has: us vs them, good vs. wrong, no room for compromise. I think extremists of all kinds, that’s sort of how they view the world. So I though here’s a chance to give you 22 minutes in the head of a guy like that.

Street: And is it kind of an examination of his politics?

NO: Some part of it is politics but it’s also like the world of [Baruch Marzel]. But there’s also stuff about his childhood. And in some ways, the scene I’m proudest of, is you have him talking about being in the 1982 war in Lebanon. At some point he kills seven prisoners of war. According to him and the Israeli army investigation, they were subdued and he says one of them threw a grenade at him. He talks about killing himself people. It’s an intense moment, and then I cut directly from that to him playing with his grandchildren. To me, the most interesting thing about spending time with him was that he was a wonderful grandfather. And I kind of expected that, but in hindsight it was my own naivete. Why wouldn’t he be a great grandfather! He wishes in the film that he could have more than nine kids. I wanted to sort of show that. I showed the film to some audiences and I’ve been attacked as humanizing him. Because in the film I’m very influenced by the filmmaker Errol Morris. And in the movie employed his style. I put a teleprompter in front of the camera so he could be looking directly into the camera but also be looking at my face. In Morris’s films he’s very objective. Morris doesn’t take a strong moral stance about the people he’s making movies about, even when you know from his other readings and stuff that Morris feels very strongly about these people. That’s not what he’s trying to do in the film. What he’s trying to do in the film is give you a closer view of that person. And that’s what I tried to do in this film. One time I showed it at a conference and someone said I was humanizing him. I’ve always thought that when someone attacks humanizing someone that we don’t like, the obvious example being Hitler, I always thought that’s a weird way of attacking someone. These people are human beings, it’s not a bad thing to recognize that. It’s like me telling you the sky is blue. Part of it is just his ideology and politics, but part of it is just how does this guy view the world? How does a guy like this view his kids? How does a guy like this view his childhood? That’s what I wanted to give you in the film.

Street: That’s interesting to me. I don’t think the term extremist is attached to far-right Zionists as often as it’s attached to Arab resistance forces.

NO: Right, and you know I have my own very strong feelings on him in the movie. If I show you the movie and you come away with a strong opinion on him but you don’t know how I stand, I’m happy with that. That to me is success. Because it’s not about how I feel. It’s about what he thinks and what you think of that.