“Put the fat one in the back,” my boss ordered me. “Put the fat one in the back so that the rest of your girls can get in. The bouncer isn’t feeling her.”

“Who are you talking about?” I asked.

“You know who I’m talking about. The pig. Put her in the back.”

“I don’t know who you’re talking about and I can’t do that.”

"If she gets in, she can’t be at our table. I can’t be seen with people like that.”

That was the first night.

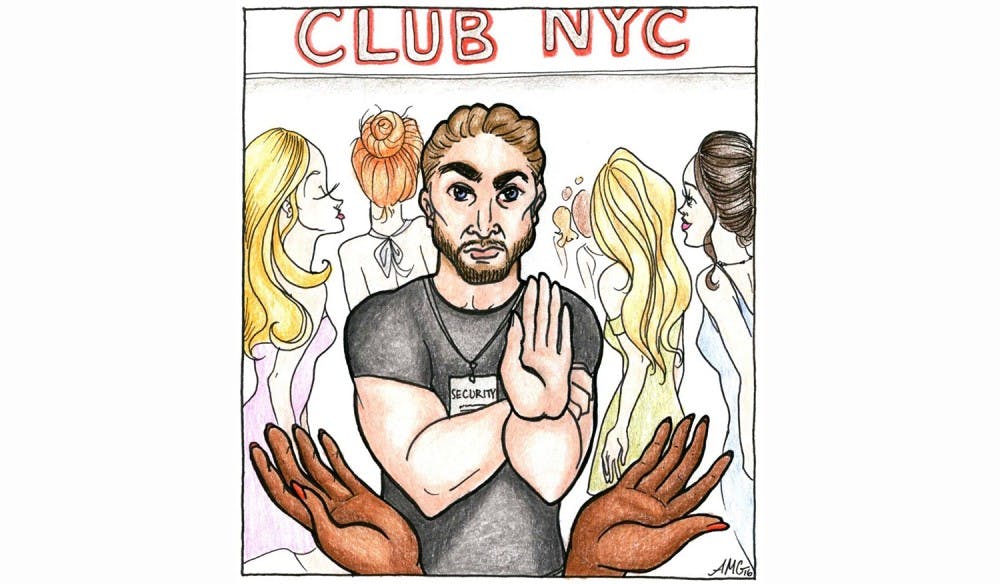

Before I became a club promoter in New York this summer, I saw the role as a glamorous, powerful position. Every weekend in the dusk of a Chelsea nightclub, a Hummer H2 limousine with tinted black windows halts just feet before the VIP entrance. Heads turn and eyes widen as 20 or so models gracefully exit in stunning Balmain, Roberto Cavalli and Tom Ford pieces. They strut past the bouncers and into the threshold of the club, apathetic toward the crowd of ogling spectators waiting hours on end for their chance to enter. Their club promoter leads the pack, a person whose job is to host the models at expensive tables adorned with fine wines and top–shelf liquors inside.

The promoter's objective: performative mirth. To giggle and shimmy and sing along to the mixes blasting from the DJ booth, all in the hopes that onlookers will succumb to the temptation of wanting to belong—joining in on the calculated “fun” with their hearts and, more importantly, with their wallets. Promoting is, at its root, an exploitation of human insecurity and vulnerability. The culture breeds and prizes greed, vanity and the belief that personal worth is contingent upon material possession. It was shallow. It was superficial. Almost laughable, even. And I wanted in. So, during the summer of 2016, I joined the ranks as a club promoter in New York City.

It had mostly started out as a joke, a job I described as "an ethnographic case study into New York City’s club scene.” Not necessarily the most reputable of openings one could come across through PennLink (I actually did apply for this through PennLink); however, in addition to my summer internship, I needed another job to mitigate the overwhelming financial burdens of living in New York for the summer and studying abroad in the fall. Plus, making money from partying every weekend didn't seem like the most arduous task.

A friend introduced me to the New York club scene last summer. We drank without care. We laughed without cue. We danced without beat. I indulged in the absurdity of the moment; I toasted the unpredictability of life. I was in the center of a world that had seemed exclusive and remote. The exhilaration was so intense that, over time, I became actively blind to the superficialities of the classist, racist, sexist and counterfeit atmosphere. I was a passive critic of my own self–exploitation.

It wasn’t long after I started promoting, however, before my rose–colored glasses began to self–destruct.

The second night:

“How much?” a man in leather and tight jeans asked me.

“To buy a bottle? I’d have to ask my boss.”

“No, you know what I mean.” He scoped my body with his eyes. “How much?”

The third night:

“I’m sorry, but you can’t get in,” a staff–worker informed me as he stood in front of the door, barring club access to me after he let my two friends in.

“But both the doorman and bouncer said that I could get in."

“Well, I’m saying that you can’t.”

“But you just opened the door for two of my friends," I said.

“Because they can get in.”

“But it isn’t your job to choose who can and can’t get in.”

“That’s not your problem.”

"But… you know what this looks like, right? You let my two friends who are white get in and you’re not letting me in.”

“That’s right.”

I stared at him. “Are you not letting me in because of the color of my skin?"

“Maybe.” He grinned.

No matter how many times I told my boss that I wasn’t going to work another day for an industry so narcissistic and vile, I found myself returning because of external financial pressures. Trapped in a purgatorial war in my mind between money and morals, I returned to the same clubs every week—laughing on cue, dancing on beat, but writhing in the pain of knowing that the “joke” job had evolved into something spiritually damning.

I was supposed to be the host. I was supposed to be in charge. And even then, I was still dissected as an object existing purely for judgment, entertainment and pleasure. The club scene unapologetically disregarded my agency as a promoter and my agency as a black woman. My experiences only exposed me to a microcosm of the intersecting, extensive and complex issues facing our society. And these problems persist at Penn.

It’s okay not to be okay with the systems around you, even if they’ve “always been that way.” And while I will always regret my passivity in engaging critically with these issues over the past summer, I have come to recognize my own complacency. I am working to take a more active role in the fight to dismantle these forces, one day at a time. After a summer crammed into clubs, it's finally time for me to face the music.

Illustration by Anne Marie Grudem.