At one Locust Street house, a Wharton junior wearing a knit cap yarmulke comes bursting through the door at four o’clock in the afternoon on a Friday. After hurriedly greeting his housemate, he walks by a common room sporting a beer pong table and his house number written in beer caps on the wall. The sun is set to go down at 5:30 that day, and he has only until then to prepare his part for the weekly Shabbat dinner. To an unknowing onlooker, this scene might seem more frat house than religious hub. The setting is inconsistent with the serious nature of the orthodox services to which he’s counting down.

Friday afternoons are pretty laid–back by Penn standards but, for the microcosm of Penn students who practice Orthodox Judaism, they are downright hectic. Just about any work that members of the Orthodox Community at Penn, or OCP, need to get done before Sunday must be finished before sundown on Friday. Once that sun dips below the horizon, members of the OCP can’t utilize technology, exchange money or even write anything down. What they can do, though, is socialize, and on Friday nights, the OCP social scene comes alive.

After about an hour of services in Hillel on a Friday night, members of the OCP scatter to various Shabbat dinners both on and off campus. Some OCP–ers stick to Hillel for the night, others head over to the second floor of Rodin, where the members of the Jewish Cultural Program live, and even more people migrate to one of the established off–campus houses that keep kosher.

These dinners are at the heart of a tight–knit religious community whose spiritual and social lives are so deeply intertwined that it’s impossible to say where one starts and the other ends. Though the members attend the same daily prayer services, Jewish life seminars and Torah learning sessions in Hillel, it all comes back to Friday nights, when members of the OCP get together to celebrate the Jewish day of rest—by hanging out with a whole lot of matzah balls and manischewitz.

The Shabbat dinners that take place outside of Hillel are grand potluck affairs where hosts welcome anywhere from five to 20 guests. And there’s more than just a variety of food; members who host dinners make it a point to invite different people to their gatherings each week—from all sects of Judaism. “Sometimes it will be everyone who did this summer program last year, or everyone who lived in this house together last year as a reunion type thing, but sometimes the hosts just choose some people they think might get along and don’t know each other yet,” College junior Tamar Friedman says, explaining the culture surrounding Shabbat dinner.

The hosts of these dinners almost take on the role of temporary social chair as they design their guest lists. They plan and send out invites towards the beginning of the week, especially because last–minute texts and invites can’t be sent the night of. Plus, the earlier an invite is sent out, the more likely it is that the person invited won’t have made another Shabbat commitment. Everybody wants to have a good time, and fun starts with a carefully crafted guest list.

The OCP has about 200 members, although it’s hard to put an exact number to it. Put frankly by Engineering junior Mordy Fried, “Saying ‘I’m a member of the OCP’ is really the only admissions process we have.” The vast member base of the OCP is involved in a spectrum of other groups on campus, from the UA to political activism to Greek life. A group of 200, though, can still seem fairly inaccessible to outsiders. Those on the edges of the OCP see the group as somewhat insular. “It’s understandable that sometimes people may feel a little intimidated, but I think that’s the case when you have a large group of students who are similarly minded,” Hillel president and Engineering junior Alon Krifcher says in response to those descriptions.Due to the OCP’s innate religious affiliation, most of the members come from similar backgrounds. Many took a gap year in Israel and attended Jewish day schools. They come to Penn already knowing other members of the OCP because they’ve done the same programs in Israel or played in the same Jewish basketball leagues. It’s not that they’re exclusive—it’s that the core of their community is based around their Orthodox Jewish upbringings.

Sitting in Hillel in the early evening, one OCP member is checking her email before a Sunday Night Learning session, and the words “Mazel Tov!” appear on the screen. A message comes in announcing the engagement of two recently graduated OCP–ers. She shrugs, unfazed, and shuts her laptop, ready to learn some Torah portions.“There’s definitely, definitely couples, and they definitely get engaged. There’s a married couple now. This past summer, three OCP couples got married who had just graduated,” College sophomore Galit Krifcher, Alon’s sister, explains of the dating culture within the OCP.

College sophomore Carly Mayer feels like this marriage mentality stems from “a focus around the family; a lot of Jewish practices are around the family, having children and such, so to a certain extent there is that culture of getting married earlier than normal.”

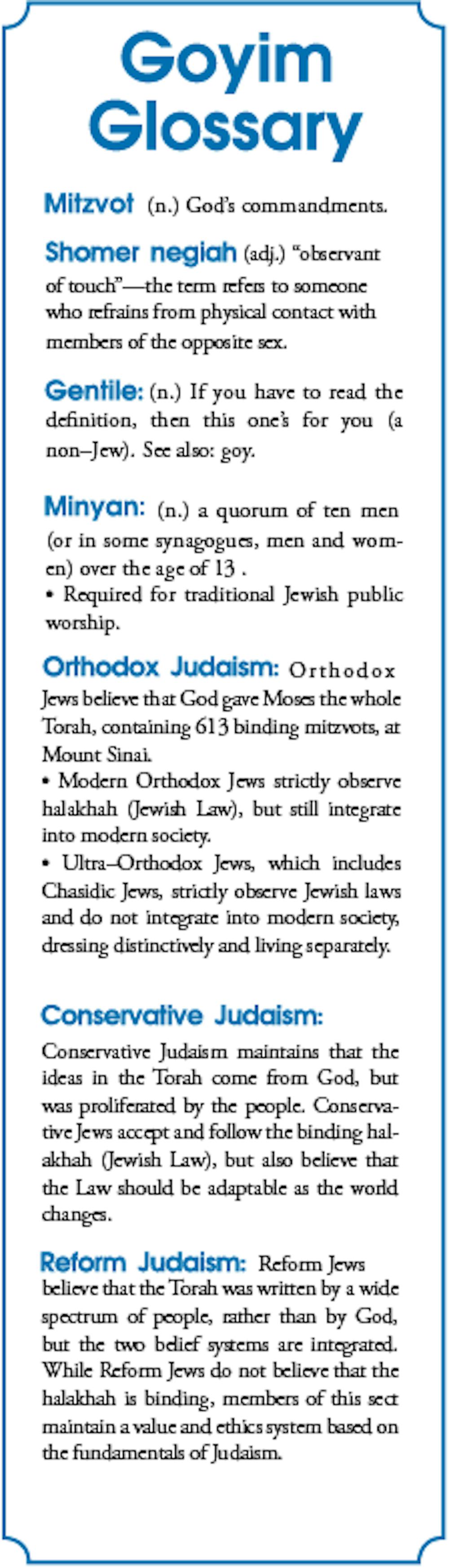

Many OCP members also take part in a Jewish practice called “shomer negiah.” This refers to the restriction against touching members of the opposite sex besides spouses and immediate family members. Not all members of the OCP are shomer negiah, but the tradition echoes the family values mentality of much of the community. Carly, who is shomer negiah, explains it as simply the right choice for her as a Jew: “I know it’s a little bit of a funny concept, but I also think there’s a lot of meaning behind it. I really just felt like it was the right thing to do, for my framework, in my Jewish practices.”

Many members of the community have the same mindset as Carly, and College sophomore Ben Bolnick goes further to explain that he thinks the physical part of relationships can “distract and detract from a relationship.” For some members of the OCP, marriage is a much more serious consideration than it is for the average Penn student, and personalities in romantic relationships are examined with more purpose.

From an outsider’s perspective, those focused on finding a significant other look like they are are rushing into marriage—or worse—that they’re only getting married in order to fast track the road to coitus. In reality, most OCP–ers who are focused on marriage are more focused on seeking out a fulfilling religious life—which for many Jews is with a vibrant family life, and family starts with marriage. For OCP–ers, negiah aids in the search for finding someone to share that family life with, but it can also cause a few awkward moments in the broader Penn community.

Mordy, who is also negiah, explains that he tries not to embarrass anyone by avoiding something like a handshake or a high–five. In one particular instance, though, he had to lay down some Jewish law for a close friend. “Freshman year, I was very close with a girl from Miami, we were in all the same introductory engineering classes. She—and I knew this was gonna happen, we were sitting in all our classes together—I knew when we got back from winter break, that she was gonna go in for the hug, and she did.” Mordy accepted the friendly embrace, but afterwards had to sit his hallmate down and explain that he’s shomer negiah, which meant that hugs would be out–of–bounds from then on.

Ultimately, though, those who are shomer negiah feel a deep religious commitment to the practice. No amount of awkward encounters is going to change their decision.

Where Penn’s dating culture is often perceived to thrive on a mixture of alcohol and vague physical attraction, those within the OCP are focused on more concrete, or as Alon refers to it, “substantial” connections. “There’s a lot less of the hook–up culture, a lot less of the ‘go to a party and make out with someone on the dance floor,’ to be frank,” he goes on to say about the OCP. Carly explains that the serious dating culture is common because “that’s how a lot of Orthodox Judaism is, even if people aren’t getting married, they’re at least trying to date, and their dating mindset is more or less...‘Can I possibly see myself with this person in the future?’” It’s easier to tell something like that when spending as much time together as members of the OCP do.

In many ways, the religious and social lives of OCP–ers are one and the same at Penn—so much so that it’s sometimes difficult to find a distinction, let alone properly dissect the two. For Galit, that’s one of her favorite parts of the group, “you don’t have to be excluded from the social element of college by being in an Orthodox community here.” At Penn, a core part of the Orthodox community is based on the social nature of the celebration of Shabbat. The religious and the social converge in the OCP, and that creates what some may describe as an insular community. However, to those within the OCP, it’s a tight knit group of individuals who share the same values and like to spend time together. Mordy described the community best, though: “we’re just religious people, and we like to have fun.”

Cassandra Kyriazis is a College sophomore from Swarthmore, PA majoring in communications. She is the Film & TV editor for 34th Street Magazine.