“We’d usually start off watching a movie and then fuck,” said Maria*, a College junior, of a woman she met online this summer. “we were always high,” she added. And the sex? “It was pretty good sex! She was a lot more aggressive than she looked.” Maria hasn’t seen the woman since the summer, though they’re not exactly incommunicado. “She still comments on my stuff on Facebook," Maria giggles.

If you remember the days when TV happened on a television set, you’ll also remember the abundance of commercials for eHarmony and Match.com, some of America’s most popular online dating services. It’s all about statistics: “One in five relationships start online” or “People who use our service are three times more likely to find a relationship.” For the long-term-relationship-seeking 30-somethings who sign up for these sites, online dating has become, to an extent, normalized. The same can’t be said for Penn students’ relationships to the services. The immediacy and connectivity that online dating offers should, in theory, be right up our alley; we’ve digitized practically all of our other social interactions, from birthday wishes to party invites. But despite the fact that we do everything else online, the idea of seriously someone who we meet on the Internet seems a little foreign, even taboo. This doesn’t mean Penn students are eschewing dating apps. We’re just not necessarily using them to date.

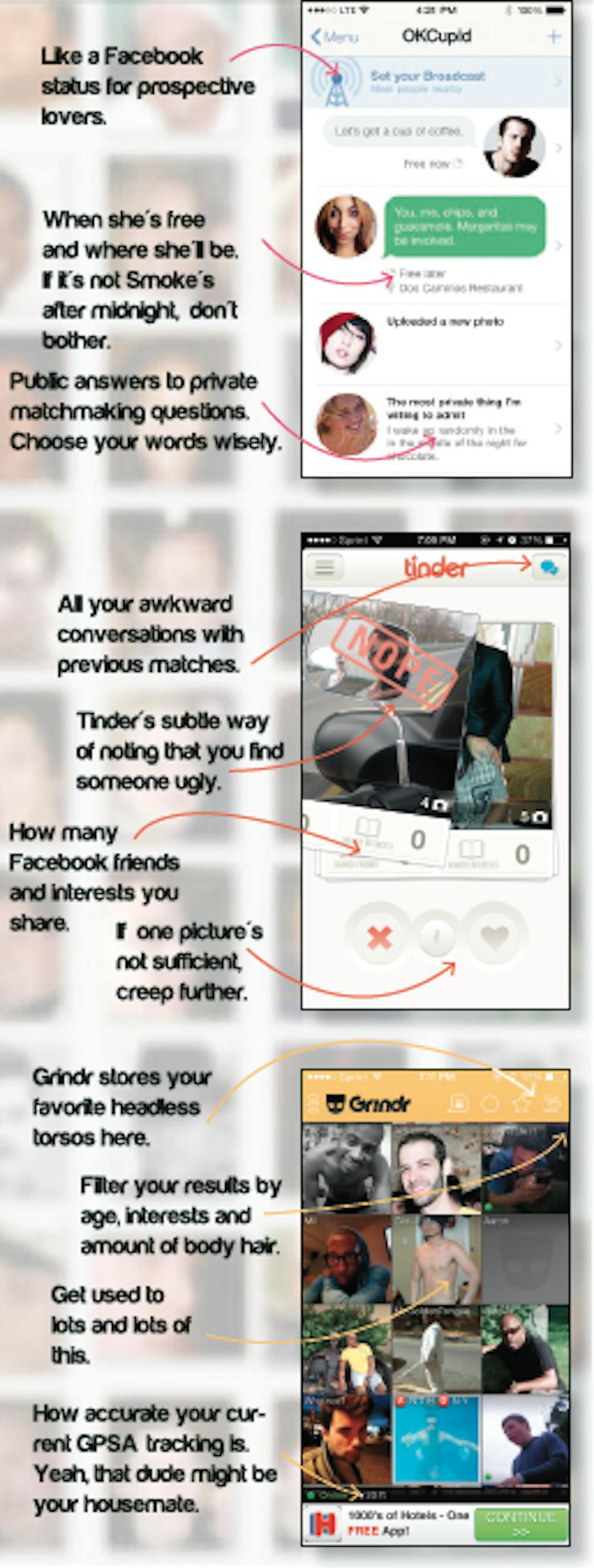

“I’m embarrassed to tell people I’m on OKCupid,” Maria said after taking a second to think. Maria signed up for OKCupid her freshman year. She arrived at Penn a newly out lesbian and was greeted by a campus whose community of queer women was not readily visible. While she her male counterparts settling into a vibrant gay scene, Maria got frustrating trying to find other lesbians. She laments, “I got [OkCupid] freshman year because it’s just so hard to find girls at Penn, and I just don’t know who’s gay.” OkCupid was Maria's attempt to identify with a larger lesbian community on a campus that seemed to be without one. Maria admits that she made a profile and would exchange messages with girls during her freshman and sophomore years, “but when it comes to meeting people, I usually don’t have time and I’m not going to go somewhere to meet up with them.” Perhaps it was more than the inconvenience of “going somewhere” that prevented Maria from meeting someone. The stigma that surrounds the use of online dating services is undeniable on college campuses. Penn is no different; filled with young, smart, libidinal undergraduates (and graduates for that matter), it is a veritable hotbed for hookup culture. So while picking up someone at Smoke’s every weekend doesn’t elicit more than an eyebrow raise, using the Internet to hook up is still murky territory underpinned with tones of desperation and danger.

It wasn’t until Maria lived in Los Angeles the summer before her junior year that she decided to give OKCupid another go. “In L.A., I used OkCupid not just to hook up; I didn’t know anyone there, so I [thought] ‘might as well meet some new people, and if we hook up, we hook up,” she says. It was a Penn alumna on OkCupid who invited Maria to a “Queer Ladies Hangout” in L.A., where Maria met a number of girls she’d been messaging on the platform; some even knew her friends at Penn. “I was surprised…it was such a small world.” She liked the seeming comfort of a community and was able to find a peer group of similarly inclined female friends, even if it was 2,600 miles away from Philadelphia.

When it came to hooking up with someone, Maria didn’t necessarily put a premium on this familiarity. She describes her first coffee date with the Australian actress-by-day-waitress-by-night whom she met on OKCupid with a chuckle: “We got along pretty well, we were both wearing plaid… typical”. Though this initial meeting was a gesture toward a first date, Maria notes it was a little contrived, “the whole time we knew that we intended to hookup.” This was made abundantly clear when Maria’s Australian friend invited her to smoke and “watch a movie” Maria added, using air quotes and rolling her eyes at the phrase. But all of this worked for Maria. She was in a new city for the summer and casually hooking up with someone was all that she really wanted or needed. Though OKCupid asks all sorts of questions of its users in order to find an ideal romantic match, she took a much more pragmatic approach to the service, not once mentioning any of the questions she was asked when finding her potential matches. For Maria, using OKCupid was “born out of necessity.” For some, the use of a dating app is far less deliberate and far more ambivalent.

Sarah*, a College senior, was a little drunk when she decided to meet one of her Tinder matches. Two weeks before, she’d downloaded the app on a recommendation from a friend. Now it was 3 a.m., Sarah was in Manhattan’s East Village and so was the attractive 20-something guy she was messaging on Tinder. The implicit “sketchiness” in meeting strangers on the internet was not lost on her. “What if I die tonight?” she had said to her friends before she left the bar to meet him, only half-joking. They were meeting somewhere near Sarah’s apartment. “If he’s weird, I’ll just walk home,” she thought. But the potential for an uncomfortable, even potentially dangerous, interaction wasn’t stopping her: “I definitely wanted to meet this dude, and go to his place and hook up.” Though Tinder bills itself as a “dating” app, it also acknowledges the fact that both parties find the other, on some level, hot. “We both swiped right…we both liked each other,” Sarah explains. A 3 a.m. Tinder message is today’s social media booty call.

“The weirdest part was waiting to meet him,” Sarah noted. More awkward still was the transition from niceties and introductions to discussing the implied purpose of the tryst: hooking up. Sarah’s AC–less, shared bedroom wasn’t the ideal venue, nor was the couch that her match was crashing on for the night, which happened to be his ex–girlfriend’s. “So we didn’t do anything and we just walked around until the sun came up, and just… talked, which was not what I was expecting. He was really nice and normal and smart and funny.” At the end of the summer, he was back in New York and slept over at Sarah’s. That was the last time Sarah saw the guy she met on Tinder and she’s fine with that: “I knew what it was; I was very fine with the way it ended.” Sarah and her match never had sex.

Part of Sarah’s attraction to Tinder was the perceived frivolity of a hook up: “It was fun because it didn’t have any consequences.” By the same token, Maria didn’t want a serious relationship during her stint in L.A., and using OKCupid to find an inconsequential friend with benefits was practical. The lack of mutual friends, overlapping relationships, flirting— all of the messy and often ambiguous extenuating circumstances that came with a typical hook up were essentially removed from the equation.

Ultimately, Tinder was not for Sarah. “Having such a rush from meeting this person to having him sleep over was very stressful for me, even though I enjoyed it on some level.” Then there’s the undeniable stigma. It’s rooted in some combination of the perceived desperation and the ever—present danger of catfishing (when someone pretends to be someone else on social media). Maria pointed to the deliberate nature of downloading an app for the sole purpose of hooking up as part of it. For Sarah, the distinction between real and online dating practices is not as clear–cut: “People are like ‘it’s so superficial’ or ‘so desperate,’ but so is going up and talking to someone who you think is hot at a bar.”

John* lost his virginity to someone he met on Grindr. “I didn’t come out until college,” he explains, “I didn’t know where to go otherwise.” The use of dating apps, for both Maria and John, was initially a means of jump–starting their gay sex lives. It was mostly curiosity that prompted John to download Grindr, and the dating app served as his first foray into the world of gay sex: “It was definitely during a time when I was experimenting.” This is not to say that John’s relationship with Grindr has ended— now a senior in Wharton, he still uses the app on occasion, “mostly when I’m bored or just horny… it’s so much easier.” It’s the instant access, the ability to reach into his pocket and be instantly connected with hundreds of other gay men—most of whom are looking for sex—that makes Grindr work for John.

Using Grindr at Penn comes with its own set of complications and John can speak from experience: “I met a Penn student on Grindr who wasn’t out… it didn’t bother me, but he was really paranoid all the time. [Now] I try to keep away from Penn kids on Grindr. I usually have to scroll [past them] because I see too many.” In the same way that Grindr gives instant access to a community of nearby, sex–seeking men, it is also a conduit to a darker side of the gay experience. Closeted guys, even married guys—some with kids—flock to the app for the same reason that John does—it just makes hooking up easier. This can complicate things even when John’s not on campus: “At home [in the Midwest] there are a lot of straight and married men; it’s awkward because sometimes I’ll see [guys I’ve hooked up with] out and about with their kids.”

John kept his voice low and cast more than a few uneasy glances about during our interview. “There is definitely a stigma, because it is very much a thing for hook ups, and you don’t want to be labeled as a slut or a whore.” Grindr, unlike OKCupid and Tinder, is designed and sold as an app for casual hook ups; it’s location based, meaning profiles of those geographically closest to the user show up first, not to mention it is limited to gay men. Nothing comparable exists (at least as effectively) for their heterosexual or lesbian counterparts—even though Maria and Sarah were able to adapt idealized “dating” tools to meet their actual needs. John, like Sarah, is not particularly clear on what makes a hook up facilitated by technology any more stigma–laden than hooking up with someone he meets at a bar, but he says, “With guys from Grindr whom I consistently hook up with, I tell my friends that we met when we were out somewhere.”

As Penn students’ social nexus becomes more and more web–based, it should come as no surprise that we’re starting to use technology to facilitate hook ups because we value efficiency and instant—if not wholly gratifying—connectedness. Though Maria, Sarah and John had different experiences with using online dating to hook up; whether it was a matter of simply finding someone, or skipping the dinner date and cutting to the chase, the use of a dating app makes getting it in so much simpler. Of course there’s always alcohol, the college standby for allaying the uncomfortable lead–up to any sexual encounter. But Bankers is gross, Smoke’s is crowded and you still haven’t heard the end of the embarrassing choices you made last weekend. With a dating app, flirting and foreplay are wrapped conveniently in with the rest of our social interactions, most of which take place in our back pocket. Shock and contempt are the last things we should feel about this burgeoning virtual hook up culture. We sext. We send questionable SnapChats. We iMessage 2 a.m. “what’s up”s when we’re drunk. Let’s be honest—we saw this one coming from a mile away.

Patrick del Valle is a junior from Seattle, WA, studying finance and OPIM. He is the Social Media Editor for 34th Street Magazine.