VHS tapes most seem like a thing of the past. They’re chunky. They’re grainy. They’re full of tape–stuff foreign to the digital age. All in all, not much to attract the modern viewer. But despite what you might think, they haven’t quite made their last exit.

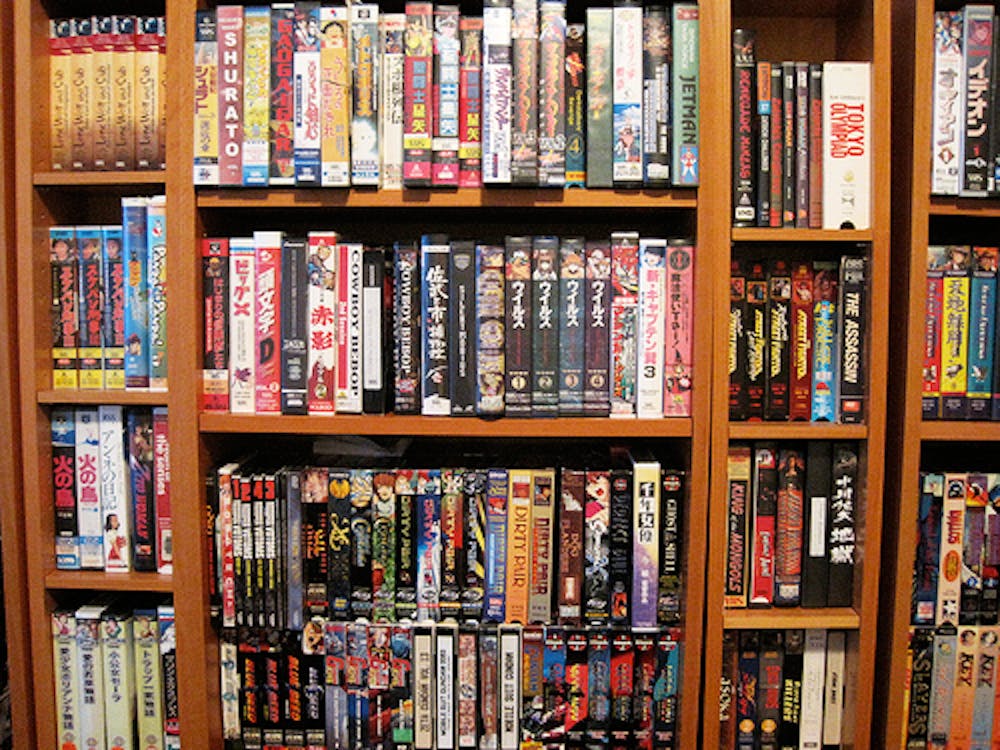

Stepping into thrift stores around Philadelphia, shoppers can still find these clunky, archaic objects on the shelves. Blockbusters and local–grown video stores might be on their way out, but places like Bainbridge Street’s Philly AIDS Thrift and Mostly Books still carry a range of films on tape — anything from an obscure, 1996 Steven Soderberg film to Citizen Kane. And people are buying.

What could possibly be the draw to VHS? Even cinephiles find the tape outdated. Penn’s Cinema Studies department, for instance, has been phasing out VHS due to lack of storage space and tape players in classrooms, according to Professor Timothy Corrigan. It makes sense. There’s just no room. If VHS might be placed in the category of older forms and dying arts, why doesn’t it just, well, die already?

But VHS might hold some advantages. The New York Times recently ran a whole spiel on the counter–culture surrounding VHS slasher films. The article, “Like the Best Zombies, VHS Just Won’t Die”, points to the cottage industry supplying those who prefer their arthouse gore like The Mutilation Man on tape. Here in Philadelphia, thrift stores have followed similar trends.

Mostly Books owner Joe Russakoff says certain niches like “weird, old horror” keep his VHS section standing, despite the fact that about 90 percent of his shelf remains unsellable, forcing him to purge hundreds of movies. In addition to those low–budget, low–quality horrors, he explains that Hollywood classics also make up a distinct number of sales. Many customers apparently find that the nostalgic feel and all that rewinding add to the experience.

Beyond aesthetics, though, the real gems of VHS thrift store diving come from rarity. According to Professor Corrigan, the Cinema Studies Department still holds a special collection of VHS — 55 tapes in total — because many important films aren’t yet available on DVD or are difficult to come by. Mr. Russakoff’s collection at Mostly Books plays to this. One such movie is Eadweard Muybridge, Zoopraxographer, a 1975 film essay by Thom Anderson that Penn holds on VHS. The short film, unavailable on DVD, takes an important look at one of the predecessors to film, early English photographer Eadweard Muybridge, following both the man's life and the origins of cinema. If a complete purge of VHS were to occur, this documentary work and other prized films would be lost.

Like Corrigan, Mostly Books employee Nick Capoferri mentions that one of his favorite films, Michael Radford’s version of 1984, is only available in its original form on VHS. Although released on DVD by MGM in 2003, the original saturation and washed–out feel — as well as its original music — have been changed, making the VHS version a rare relic. Stumbling upon archaic finds like these, whether just a DVD rarity or a film simply unavailable in newer forms, can make VHS shopping more worthwhile.

Mr. Russakoff adds that going through the old movies brings back a certain intimacy from the era of mom–and–pop shops, saying, “that whole culture of video stores — there’s kind of a remnant of it here.”

VHS could easily be placed into the larger debate of society’s shift toward big business and digital technology. Mostly capsized by YouTube, Netflix and pirating sites, in some ways tapes and even DVDs fit in with CDs, cassettes, print newspapers and books.

Thrift stores — not even a block from Philly AIDS Thrift and Mostly Books — have discontinued their VHS sections. According to employee Dan Balcer, the Record Exchange stopped selling VHS because no one purchased. There was simply no demand.

Yet, that same Record Exchange brims with vinyl, probably once thought extinct as well. Perhaps some hope remains for VHS then, although any comeback will probably grow more from indulgence of nostalgia than utility.