It’s easy to forget that people make things anymore. America’s cities are filled with shuttered and rusting factories. Its politicians speak of saving and creating industrial jobs, using outdated rhetoric that might be funny if it didn’t hurt so much.

American industrialism is a fading memory that casts a long shadow. Pre–industrial artisanship is an even dimmer epoch, the province of “living history” setups like Colonial Williamsburg. But there remain a few fields whose practitioners approach making goods by hand as neither educational gimmick nor countercultural utopianism (a la the slow food movement). Surely, people who practice such anachronistic crafts must be anachronistic people — like the man who works, for instance, behind a sign on Spruce Street that reads: “Christopher Germain, Violinmaker,” which brings to mind a man wearing a powdered wig and breeches.

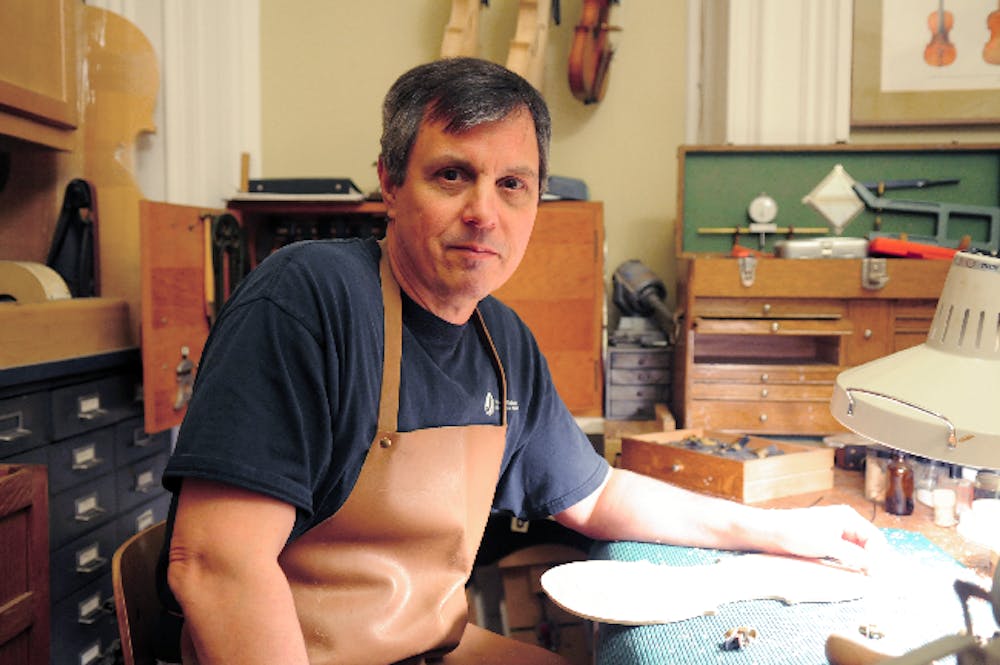

Christopher Germain doesn’t wear a powdered wig. He favors faded Levis over breeches, and he wears running shoes each time we meet. With his soft face and graying hair, he resembles a middle–aged Paul McCartney. Located near Rittenhouse Square, Germain’s workshop occupies two rooms on the first floor of a building that also houses his living quarters. Along the left wall is a case filled with a row of violins; along the right wall is its counterpart, filled with books (Stradivari’s Varnish, among others). A rack of cellos sits in front of this cabinet. With a marble fireplace and a plush rug, the space brings to mind Sherlock Holmes’s drawing room. A pair of wood and glass doors open onto Germain’s workshop, which is orderly but not stuffy; work clearly takes place here.

Germain’s shop sports markedly little in the way of digital technology, save for a computer, two printers, a telephone and some speakers that are always playing classical music. Everything else works on the principle of a hand applying force: chisels and planes and brushes and awls. These are all Germain needs. These, and his hands.

“The process has not changed all that much in three or four hundred years,” Germain says in his flat Midwestern voice. “Compared to other professions, where everything is completely changing in a few years or months, violinmaking is a very tradition–oriented craft, and although there’s access to information that was not available before, the actual way the instrument is made is pretty much the same.”

The information that Germain speaks of is itself of a backwards bend; it refers to new insights that technology has provided into the methods used by the violinmaking masters who worked in Cremona, Italy in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, members of the families Amati, Guarneri and Stradivari. Violin enthusiasts tend to speak of these families with the hushed reverence uttered in the presence of the divine. From time to time, a newspaper headline heralds new revelations about “Stradivari’s secret” as if it were King Tut’s Curse.

Germain does not participate in the breathless search for Stradivari’s quintessence. Asked about the secret, Germain responds with a craftsman’s pragmatic passion. “I don’t think there was a secret,” he says. “I think there were a thousand secrets. It’s like saying if I had the paint that Michelangelo used to produce the Sistine Chapel, then I could do that, too. Well, no. I couldn’t do that. The secret is that these guys were geniuses — they were working at the height of their craft, there were many fine craftsmen at that time, they were working in close proximity, it was a very competitive field and they were at the top of their game, just like Beethoven or Mozart. That’s really the secret, I think, not some recipe that was long lost and is waiting to be rediscovered.”

Talking to Germain, you get the sense that the need for a mystical explanation irks him a bit. And why wouldn’t it? What to others may be a letdown or a dull story is to Germain a way of life, one that yields rewards and excitements much greater than the conspiratorial search for some superhuman additive in the Cremonese makers’ method. It’s as if mere genius were no longer compelling enough.

It suffices for Germain, however, who began his career nearly 30 years ago. Born in St. Louis, he earned a degree in journalism from the University of Missouri in 1980. But by graduation day, Germain had no intention of using his degree; he had already decided to become a violinmaker and completed a journalism program to appease his parents. Germain was drawn to violinmaking as a merging of two early passions: music and making things. “When I was young, I just loved working with my hands, making stuff,” Germain says, adding that he would often spend time in his father’s home workshop trying to make things from scraps of wood.

After a brief money–saving interlude at the St. Louis Post–Dispatch, Germain headed to the newly–founded Chicago School of Violinmaking.

After graduation, Germain worked with two violin dealers in Chicago, “learning a lot, but not making a lot of money.” A degree in violinmaking does not mean the end of training; for those aspiring to the heights of the craft, an apprenticeship is common. “If you’re going to go into violinmaking it has to be a strong desire. It’s so challenging, it’s so difficult, it’s so hard to make a living for a long time. It’s like being a starving artist,” Germain says.

Germain started his own business in Chicago in 1991, where he worked for six years before relocating to the Washington, D.C. area. A decade later, Germain chose to come to Philadelphia, where he opened his first real shop. Many violin makers work in home workshops, but Germain’s reputation had solidified to the point where he thought “it was time to be a little more visible.”

Hiding wouldn’t do Germain much good. His Midwestern humility means you have to pick up the threads here and there, but it’s clear that Germain is an eminent figure in the violinmaking world. When I ask Germain’s apprentice, a taciturn young man named Sam with a voice that is somehow both high and deep, how he found out about Germain, he replies, “He’s famous.”

“Infamous,” Germain immediately quips, a smile flickering across his face.

Germain’s prominence ultimately derives from the quality his work. His violins, violas and cellos are painstakingly crafted in much the same way they were centuries ago. Germain begins an instrument with a pattern derived from one of the Cremonese designs, which provides an outline. Using a hot iron, he bends a piece of wood to make the instrument’s sides, or ribs. He cuts the top and bottom pieces to fit this outline, thus creating the violin’s body. The ribs, the bottom and the neck are all typically made from maple, while the top is usually spruce, chosen for being light and resonant but also strong.

The body will receive several coats of varnish, made from pine or fossil resins, giving it a rich amber glow. Since these varnishes don’t dry by evaporation, Germain places varnished instruments in an ultraviolet box to accelerate the process, so that he doesn’t have to rely on sunlight. Germain is particularly well–known for manipulating his instruments’ varnish so that they look well–used, though he doesn’t do this for all his instruments — some of his customers prefer to break them in on their own.

Between assembling the body and varnishing and stringing it up, Germain faces innumerable choices about carving, cutting, chiseling, shaving and so on. Only by experience, he says, does a violin maker gain the intuition to navigate these choices. By intuition, Germain means the innate knowledge of the right choice at each juncture of the assembly process, earned through his 30 years of work.

Germain makes a compelling argument for proceeding in this manner: “[Other violinmakers] a lot of times feel if they can measure everything, they can produce the best instrument and I always counter with the argument that back in Stradivari’s day, he didn’t have any fancy equipment. He just used his hands and his ears and the wood and his tools, and I think that that’s still the most successful way to produce a good instrument. It’s not to say that we can’t learn from technology, but I didn’t get into it because of my love of technology. It’s my love of a traditional craft, and it’s one of the few things that is still done in the same manner today.” Since violinmaking is such a delicate and complex process, each stage accompanied by endless planing and scraping to give the instrument exactly the right shape, this intuition separates the good from the great.

If his clients are any indicator, Germain falls under the latter classification. His instruments are in major symphonies across the nation, including Philadelphia's and Chicago's; he once made a viola for a member of La Scala, the renowned Milanese opera house. He recently sold a violin to the concertmaster of the Marine Corps Orchestra. Known as “The President’s Own,” they provide classical music at the White House. In addition to these high–profile clients, Germain’s instruments are popular among all types of serious musicians, especially conservatory students.

Germain’s violins sell for about $20,000 and take about a month to complete, meaning that his annual output is fairly small. He could produce more, he says, but repairs and restorations occupy much of his time. Moreover, he enjoys his small–batch approach. “If it was a big output, it would be almost like a factory,” he says.

Quality in a violin is difficult to define, because the instruments change as they age. “Most instruments as they’re played more tend to open up and become more resonant and just freer–sounding, whereas an instrument that’s just completed generally doesn’t sound so good right away,” Germain says. A violinmaker must be patient, because a violin is never really finished, its sound receding and reviving depending on how often it is played. It’s not a process that violin makers fully understand, and it’s one of only two times in our conversations that Germain reverts to a more mystic sense of his craft. “There’s almost like a magic there, it’s hard to explain a lot of what’s involved,” he says.

The other time occurred during a phone call Germain received from a woman in Colorado, hoping to purchase a violin for her young son. Germain repeatedly encouraged her to come to Philadelphia, emphasizing that her son needs to try out a number of violins to figure out which one suits him best. “I’m not a very mystical person,” he says at one point, “but there really is a magic there, when you find the instrument you like.”

To make violins the way Germain does, patience is a must. Not the patience required to stand in a long Starbucks line, mind you. The patience in question is unceasing, not a virtue to call upon but an element to breathe.

With a devotion to so many choices that don’t register on the prevailing cultural seismographs of value — money and utility — patience may be Germain’s version of Stradivari’s secret. One afternoon, I watch Germain work on a bridge, one of the smallest pieces of a stringed instrument. It's one of the final steps in the process. I expect the process to take a few minutes, but as Germain whittles and chisels and checks to see if the bridge is flush to the near–completed violin — a gorgeous instrument with an amber finish so lively it seems to hum — I begin to get fidgety. How long does this usually take? I ask.

“Well, you want it to fit just right,” Germain says. With the smile peeking from the corners of his mouth, he adds: “Of course, when you’re talking to someone, it can take a little longer.”

Jim Santel is a College senior studying English. He's originally from St. Louis.